I wrote some notes a few months back on Pandaemonium on Rethinking the idea of ‘Christian Europe‘. I reworked that post into an essay, which has now been published in the latest issue of New Humanist. And I’m posting it here, too.

UPDATE: The original post (which is much longer than this essay) won the 2011 3QD Politics and Social Sciences Prize.

In the warped mind of Anders Breivik, his murderous rampage in Oslo and Utøya earlier this year were the first shots in a war in defence of Christian Europe. Not a religious war but a cultural one, to defend what Breivik called Europe’s ‘cultural, social, identity and moral platform’. Few but the most psychopathic can have any sympathy for Breivik’s homicidal frenzy. Yet the idea that Christianity provides the foundations of Western civilization, and of its political ideals and ethical values, and that Christian Europe is under threat, from Islam on the one side and ‘cultural Marxists’ on the other, finds a widespread hearing. The erosion of Christianity, in this narrative, will lead inevitably to the erosion of Western civilisation and to the end of modern, liberal democracy.

The claims about the ‘Muslim takeover’ of Europe, while widely held, have also been robustly challenged. The idea of Christianity as the cultural and moral foundation of Western civilisation is, however, accepted as almost self-evident – and not just by believers. The late Oriana Fallaci, the Italian writer who perhaps more than most promoted the notion of ‘Eurabia’, described herself as a ‘Christian atheist’, insisting that only Christianity provided Europe with a cultural and intellectual bulwark against Islam. The British historian Niall Ferguson calls himself ‘an incurable atheist’ and yet is alarmed by the decline of Christianity which undermines ‘any religious resistance’ to radical Islam. Melanie Phillips, a non-believing Jew, argues in her book The World Turned Upside Down that ‘Christianity is under direct and unremitting cultural assault from those who want to destroy the bedrock values of Western civilization.’

Christianity has certainly been the crucible within which the intellectual and political cultures of Western Europe have developed over the past two millennia. But the claim that Christianity embodies the ‘bedrock values of Western civilization’ and that the weakening of Christianity inevitably means the weakening of liberal democratic values greatly simplifies both the history of Christianity and the roots of modern democratic values – not to mention underplays the tensions that often exist between ‘Christian’ and ‘liberal’ values.

Christianity may have forged a distinct ethical tradition, but its key ideas, like those of most religions, were borrowed from the cultures out of which it developed. Early Christianity was a fusion of the Ancient Greek thought and Judaism. Few of what are often thought of as uniquely Christian ideas are in fact so. Take, for instance, the Sermon on the Mount, perhaps the most influential of all Christian ethical discourses. The moral landscape that Jesus sketched out in the sermon was already familiar. The Golden Rule – ‘do unto others as you would have others do unto you’ – has a long history, an idea hinted at in Babylonian and Egyptian religious codes, before fully flowering in Greek and Judaic writing (having independently already appeared in Confucianism too). The insistence on virtue as a good in itself, the resolve to turn the other cheek, the call to treat strangers as brothers, the claim that correct belief is at least as important as virtuous action – all were important themes in the Greek Stoic tradition.

Perhaps the most profound contribution of Christianity to the Western tradition is also its most pernicious: the idea of Original Sin, the belief that all humans are tainted by Adam and Eve’s disobedience of God in eating the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. It was a doctrine that led to a bleak view of human nature; in the Christian tradition it is impossible for humans to do good on their own account, because the Fall has degraded both their moral capacity and their willpower.

The story of Adam and Eve was, of course, originally a Jewish fable. But Jews read that story differently to Christians. In Judaism, as in Islam, Adam and Eve’s transgression creates a sin against their own souls, but does not condemn humanity as a whole. Adam and Eve were as children in the Garden of Eden. Having eaten of the Tree of Knowledge, they had to take responsibility for themselves, their decisions and their behaviour. In Judaism, this is seen not as a ’fall’ but as a ‘gift’ – the gift of free will.

The story of Adam and Eve was initially, then, a fable about the attainment of free will and the embrace of moral responsibility. It became a tale about the corruption of free will and the constraints on moral responsibility. It was in this transformation in the meaning of Adam and Eve’s transgression that Christianity has perhaps secured its greatest influence, a bleak description of human nature that came to dominate Western ethical thinking as Christianity became the crucible in which that thinking took place. Not till the Enlightenment was the bleakness of that vision of human nature truly challenged.

Not only are the key ethical principles of the Christian tradition borrowed from pagan philosophies, but that tradition has been created as much despite the efforts of Christian Church as because of them. The collapse of the Roman Empire under the weight of the barbarian invasions of the fourth and fifth centuries left Christian clergy as the sole literate class in Western Europe and the Church as the lone patron of learning. But if the Church kept alive elements of a learned culture, Church leaders were ambiguous about the merits of pagan knowledge. ‘What is there in common between Athens and Jerusalem?’, asked Tertullian, the first significant theologian to write in Latin. So preoccupied were devout Christians with the demands of the next world that to study nature or history or philosophy for its own sake seemed to them almost perverse. ‘Let Christians prefer the simplicity of our faith to the demonstrations of human reason’, insisted Basil of Caesarea, an influential fourth century theologian and monastic. ‘For to spend much time on research about the essence of things would not serve the edification of the church.’

Christian Europe rediscovered the Greek heritage, and in particular Aristotle, in the thirteenth century, a rediscovery that helped transform European intellectual culture. It inspired the work of Thomas Aquinas, perhaps the greatest of all Christian theologians, and allowed reason to take centre stage again in European philosophy. But how did Christian Europe rediscover the Greeks? Primarily through the Muslim Empire. As Christian Europe endured its ‘Dark Ages’, an intellectual tradition flowered in the Islamic world as lustrous as that of Ancient Athens before or Renaissance Florence after. The discovery, and translation into Arabic, of Aristotle, Plato, Socrates and other Greek philosophers helped launch the golden age of Islamic scholarship.

Arab scholars revolutionised astronomy, invented algebra, helped develop the modern decimal number system and established the basis of optics. But perhaps more important than the science was the philosophy. The Rationalist tradition in Islamic thought, culminating in the work of Ibn Sina and Ibn Rushd, is these days barely remembered in the West. Yet its importance and influence, not least on the Judeo-Christian tradition, is difficult to overstate. Ibn Rushd especially, the greatest Muslim interpreter of Aristotle, came to wield far more influence within Judaism and Christianity than within Islam. It was through Ibn Rushd that West European scholars rediscovered their Aristotle, and his commentaries shaped the thinking of a galaxy of philosophers from Maimonides to Aquinas.

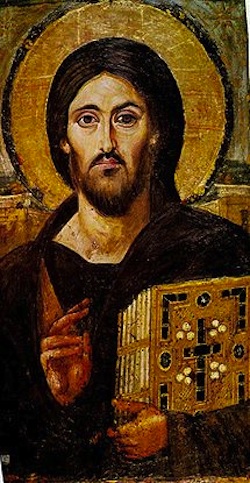

Christians of the time recognized the importance of Muslim philosophers. In The Divine Comedy Dante places Ibn Rushd with the great pagan philosophers whose spirits dwell not in Hell but in Limbo, ‘the place that favor owes to fame’. One of Raphael’s most famous paintings, The School of Athens, is a fresco on the walls of the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican, depicting the world’s great philosophers. And among the pantheon of celebrated Greek philosophers stands Ibn Rushd.

Today, however, that debt has been almost entirely forgotten. There is a tendency to think of Islam as walled-in, insular, hostile to reason and freethinking. Much of the Islamic world came to be that way. But the fact remains that the scholarship of the golden age of Islamic thinking helped lay the foundations for the European Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution. Neither happened in the Muslim world. But without the Muslim world, it is possible that neither may have happened.

If the story of the Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution has been rewritten in the interests of creating a mythical ‘Christian Europe’, so too has the story of the relationship between reason and faith in the Enlightenment. What are now often called ‘Western values’ – democracy, equality, toleration, freedom of speech, etc – are the products largely of the Enlightenment and of the post-Enlightenment world. Such values are, of course, not ‘Western’ in any essential sense but are universal; they are Western only through an accident of geography and history.

A complex debate has arisen about the relationship between the Enlightenment and the Christian tradition. As the notion of the Christian tradition and of ‘Western civilization’ have become fused, and as the Enlightenment has come to be seen as embodying Western values, so some have tried to co-opt the Enlightenment into the Christian tradition. The Enlightenment ideas of tolerance, equality and universalism, they argue, derive from the reworking of notions already established within the Christian tradition. Others, more ambiguous about the legacy of the Enlightenment, argue that true liberal, democratic values are Christian and that the radicalism and secularism of the Enlightenment has only helped undermine such values.

Both views are wrong. For a start, the historic origins of many of these ideas lie, as we have seen, outside the Christian tradition. It is as apt to describe concepts such as equality or universalism as Greek as it is to describe them as Christian. In truth, though, the modern ideas of equality or universality are neither Greek nor Christian. Whatever their historical origins, they have become peculiarly modern concepts, the product of the specific social, political and intellectual currents of the modern world.

Moreover, the great figures of the Christian tradition would have been appalled at what we now call ‘Western’ values. In his book Reflections on the Revolution in Europe, the American writer Christopher Caldwell argues that Muslim migration to Europe has been akin to a form of colonization, threatening the very foundations of European civilization. Yet Caldwell also acknowledges that ‘What secular Europeans call “Islam” is a set of values that Dante and Erasmus would recognize as theirs’. At the same time, the modern, secular rights that now constitute ‘core European values’ would ‘leave Dante and Erasmus bewildered.’ There is, in other words, no single set of European values that transcends history and binds together the Christian tradition in opposition to a single corpus of timeless set-in-stone Islamic values.

Not only are ‘Christian values’ and ‘Islamic values’ more complex, and with a more convoluted history than contemporary narratives suggest, so too is the relationship between Enlightenment ideas and religious belief. There were, in fact, as the historian Jonathan Israel has pointed out, two Enlightenments. The mainstream Enlightenment of Kant, Locke, Voltaire and Hume is the one of which we know and which provides the public face of the movement. But it was the Radical Enlightenment, shaped by lesser-known figures such as d’Holbach, Diderot, Condorcet and, in particular, Spinoza that provided the Enlightenment’s heart and soul.

The two Enlightenments divided on the question of whether reason reigned supreme in human affairs, as the radicals insisted, or whether reason had to be limited by faith and tradition – the view of the mainstream. The attempt of the mainstream to hold on to elements of traditional beliefs constrained its critique of old social forms and beliefs. The Radicals, on the other hand, were driven to pursue their ideas of equality and democracy to their logical conclusions because, having broken with traditional concepts of a God-ordained order, there was, as Israel puts it, no ‘meaningful alternative to grounding morality, political and social order on a systematic radical egalitarianism extending across all frontiers, class barriers and horizons.’

The moderate mainstream Enlightenment was overwhelmingly dominant in terms of support, official approval and prestige. But in a deeper sense it proved less important than the radical strand. What Israel calls the ‘package of basic values’ that defines modernity – toleration, personal freedom, democracy, racial equality, sexual emancipation and the universal right to knowledge – derive principally from the claims of the Radical Enlightenment. Most Enlightenment philosophies were believers (though not necessarily theists) and their Christian faith shaped their ideas. Yet what we now call ‘Western values’ were honed arguably as much by thinkers who rejected the Christian tradition as by those who embraced it.

To challenge the myths and misconceptions about the Christian tradition is not to deny the distinctive character of that tradition (or traditions), nor its importance in incubating what we now call ‘Western’ thought. But the Christian tradition, and Christian Europe, is far more a chimera than a pure-bred beast. The history of Christianity, its relationship to other ethical traditions, and the relationship between Christian values and those of modern, liberal, secular society is far more complex than the trite ‘Western civilization is collapsing’ arguments acknowledge. The irony is that the defenders of Christendom are riffing on the same politics of identity as Islamists, multiculturalists and many of the other ists that such defenders so loathe.

The reason to challenge the crass alarmism about the decline of Christianity is not simply to lay to rest the myths about the Christian tradition. It is also because that alarmism is itself undermining the very values – tolerance, equal treatment, universal rights – for the defence of which we supposedly need a Christian Europe. The erosion of Christianity will not necessarily lead to the erosion of such values. The crass defence of Christendom against the ‘barbarian hordes’ may well do so.

Saint Augustine couldn’t do it, but can someone else explain what kind of fruit Adam and Eve ate in the story? This may sound silly, but after 6000+ years we deserve an intelligent explanation. No guesses, opinions, or beliefs, please–just the facts that we know from the story. But first, do a quick Internet search: First Scandal.

The ‘fruit’ is the ‘fruits’ of this world… The attachment TO the physical things of this world. If there ever was a piece of biblical writing that cries out for symbolic reading the story of Eden is it.

Thanks. Don’t ever remember reading or hearing that before. And it fits well with the rich man Jesus was talking to not wanting to give up his possessions, And with the first Commandment and the first Beatitude.

splendid blog – reasoned and tolerant – oh for more like this .

I have always said that the core truths every religion seem to have are in fact the only way forward for a social group – as soon as we lived in groups do unto others etc. make perfect sense – embroider it with faith if we will but it is a society thing.

I agree that the so called ‘fight’ against Islam is bringing our some very un-christian emotions.

Thanks!

As a homosexual and aware of how Christians dealt with that, I can say that fighting is absolutely not an “un-Christian emotion”.

Thanks for your excellent essay. Only two comment:

1.to emphasize the importance of Ibn Rushd in European history you may use another painting than ‘The school of Athens’ by Raphael: it is Giorgione da Castelfrancos’ painting (1509) of the three wise man.On the right is Ibn Rushd, on the same level is Aristotle on the extreme right, and the young wise man is unknown. see:

Giorgione was a famous Venetian painter, His town was dealing with, was connected to the islamic world, Raphael was working for Rome. That town/church was fighting the Islamic world in these days.

2.There is an even more direct link between proto-enlightenment in Islamic Spain and Spinoza. It is the translation of ‘Hayy ibn Yaqzan’ of the Islamic philosopher Ibn Tufayl (12th century) in 1671-1672 in Dutch by Spinoza himself or (more likely) his friend Bouwmeester. The philosophy of Ibn Tufayl and Spinoza are at least ‘connected’, very strongly in my personal opinion. And there is also a connection between Ibn Rushd and Ibn Tufayl.

Thanks, that is very useful. There is a long section in my book on Ibn Tufayl and Hayy ibn Yaqzan and impact of the book upon Enlightenment thinkers. I had not realised, however, that Spinoza had possibly translated the work.

And Judaism took it from ancient Egyptian belief. It is not religious values which matter but enlightened values which matter and on which civilization depends.

There’s a vast generalization of Judaism.

Sylvain Guggenheim’s Aristote au Mont Saint Michel shattered the myth that Arab scholars were mostly responsible for reintroducing Aristotle back into Europe. It should be more cited and studied by Western philosophers…

I know Guggenheim’s work. And, no, it doesn’t shatter the ‘myth’ of the influence of the Muslim Empire upon Christian philosophy or, for instance, the importance of Ibn Rushd’s commentaries on European understanding of Aristotle. That, however, is for another post.

Christianity has always wrapped itself in the flag and colours of other traditions, according to local tastes. Then it seeks to intertwine and equivocate local and Christian culture. Christianity as cuckoo, Christianity as vampire. Real decent human values require no mythology and no mysterious eyelid fluttering shenanigans.

Religion is a disease of the mind, and the truth is the cure. Delighting in finding decent values intertwined with religious hokum is a mistake. The truest values are the universal ones, which is why embracing the secular and relegating the fluttery-eyed hokum to a position of disempowerment should be the ambition of all human societies.

How can a person be a Christian believer yet not necessarily a theist?

He or she can be a deist, believing in a Creator but not one that intervenes in human affairs or can suspend the laws of nature, and disbelieving, for instance, of miracles. It was an important tradition in the Enlightenment – Thomas Paine, for example was a deist. To some extent, the deist-theist debate relates to the debate between the idea of God as the condition of being and the God of Scripture, a debate that I touch upon here.

I understand what a deist is, but can’t fathom how one can be a Christian and a deist at the same time. Christianity at its root is all about theism and an interventionist god.

As an atheist I cannot answer that, if what you mean is ‘Who is a real Christian?’. There are, of course, many strands of Christianity that deny many of the doctrines that are often seen as central to the Christian faith, from Original Sin to the Trinity. As for deism, many (though not all) contemporary Quakers certainly see themselves as both Christian and deist.

The writer doesn’t mention the Eastern Roman empire’s influence on Islamic and western civilization.

True. Unfortunately I cannot cover everything. The Reformation is another important area, for instance, that I haven’t touched upon here. The Eastern tradition certainly had an important influence both on Islam and the Western Church. You’ll just have to read my book on the history of moral thought when it comes out, which does touch upon it :-).

You are absolutely correct on your reference to the Eastern Roman Empire’s legacy.

It is a common omission of dilettantes.

Better if Mr. Malik stuck to neurobiology.

My apologies to Mr. Malik. Your reply to JM’s post did not show up on my screen. Your reasons for not mentioning the Eastern Roman Empire accepted.

I wonder if you are attacking a straw-man here. It’s true that committed Christians usually believe faith underpins the values of the free world. Maybe a few other tag along. But does that idea really have much traction outside Christian circles. It seems that your reading of history is pretty much the mainstream one nowadays.

Yes, I agree. It seems a few scattered intellectuals lately have expressed alarm about loss of Western Enlightenment values in the decline of Christianity vis-a-vis Islam. And a few committed Christians have tried to show that modern Western ideas of rationalism, tolerance and equality, along with modern science, grew out of Christianity. But these are like ripples. The vast majority of secularists believe and have believed for generations now that these values grew and spread in spite of, not because of, Christianity. So apart from those little ripples, the article is attacking a straw man.

I disagree. We are not talking here about ‘scattered intellectuals’ but a much more pervasive social sense, and one that has become more entrenched in the post 9/11 era, that ‘Western values’ are inextricably linked with the Judeo-Christian tradition. It’s a sense that has acquired both liberal and conservative forms, fuelled by the politics of identity and notions of the ‘clash of civilizations’, and is not confined to the ranks of ‘committed Christians’.

Protestant Christianity gave rise to the idea that everyone stands before God capable of understanding God’s purpose, and needs no intervening authority, which shatters the idea that rulers and priests serve by divine authority. This grants moral sanction to citizens to question the unlimited and arbitrary power of the State and the Church. This, more than anything else, is the bedrock of “Christian Europe”. If this vision dies, Europe is just a stretch of ground to be fought over by competing authoritarian ideologies.

Sure, the Protestant idea of the individual believer, standing alone before God and interpreting the Bible according to his or her own private conscience, has played an important part in the development of liberal democracy. However, as I pointed out in my earlier essay on Luther, the Reformation was a deeply paradoxical movement, or set of movements. On the one hand, Luther’s rebellion against the Catholic Church was an intensely conservative religious reaction against the spirit of reason that Aquinas had introduced into Christianity. On the other, it was also the source of a radically libertarian revolution, the harbinger of a liberal modernity. As I put it in my earlier post

Remember that Luther, Calvin and the Protestant elite were deeply hostile to the radical Protestant movements, from the Anabaptists to the Levellers, who placed particular importance on democracy and the individual conscience. It’s important, too, to consider the impact not just of the Reformation but also of the Renaissance and of its celebration of the ‘dignity of Man’. The entanglement of the Reformation and the Renaissance limited the Augustinian bleakness of the Lutheran vision and allowed Protestantism to flourish in many forms. At the same time, the social changes engendered by the Reformation eased the way for the more optimistic Renaissance vision. As for questioning the ‘arbitrary power of the state and church’, the real source of that lay in the Enlightenment.

Protestant thought probably motivated or enabled some individuals to question divine authority of rulers and priests, but the originators of Protestant separation – Luther, Calvin, Henry VII – were clear they were divinely ordained and had absolute authority over the faith and life of their subjects; and they exercised that presumed divine authority by killing those who dissented from or opposed them in any way. Many of their successors followed suit. Protestantism was not and is not humanism; it does not automatically lead to what many now think of as Western values of democratic rule, human rights, or tolerance of religious difference.

Pingback: This week’s articles of note › The American Situation

Hi Kenan, I posted this on Google+ and got the following comment: ‘… you are talking about the Catholic Church which believes itself to be Christian. The Catholics have taken pagan rituals and infused them into their traditions since the beginning of their church. However, true Christians believe only in the Word of God. If it is in the Bible, then it is true.

Ah yes, the ‘true Christian’. I wouldn’t want to waste too much time arguing about the ‘if it’s in the Bible, it’s must be true’ claim. If anyone really believes that Genesis or the tale of Adam and Eve or the story of Job or of Jonah are literally true as opposed to being fables that attempt to throw light upon the human condition, then there is little I can say (or you can say) that will convince them otherwise. However, irrespective of how one reads the Bible, and whoever one defines as a ‘true Christian’, my point that much of Christian belief, including that which is in the Bible, is borrowed from outside remains valid. To take just one example that I gave in the essay: Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant all draw upon the themes in the Sermon on the Mount, and those themes all come originally from outside of Christianity.

Thank you Kenan.

This appears to me to be more of a history lesson about the changes in religion, than a disclaimer of Christian theology.

Christian thought from the Pulpit seems to be flexible and Preachers of all stripes seem to bend to the thinking of their constituents. There is a general fear of losing one’s audience.

The prominence of Greed threatens basic Christian values regardless of who is responsible for the original thought of certain values that Christians have espoused.

Thanks for an excellent essay. As to whether there really is a loud intellectual voice expressing concern about the loss of Christian values and civilization — it probably depends on which side of the Atlantic one is listening to. An American intellectual saying this will have his voice amplified by a big echo from the popular, socially conservative, political wall, while a European intellectual can be thankful if there’s any echo at all.

You really must get one of those “subscribe” widgets, so that people do not have to make inane comments, just so they can click on “notify me of new posts” under the reply box.

Thanks for this. There is a ‘subscribe’ widget but, unfortunately, it only appears on the home page.

It is true that an “intellectual tradition flowered in the Islamic world”. It is often forgotten however that a lot of this knowledge was transmitted through Christians, Jews, Persians and others living in the Islamic world.These people were not ethnic Arabs or Muslims though some may have converted. They were the direct inheritors of the civilization of late antiquity.

Pierre Bayle is the most important advocate of religious toleration as a matter of principle. http://catalog.libertyfund.org/index.php?page=shop.product_details&flypage=flypage.tpl&product_id=1154&vmcchk=1&option=com_virtuemart&Itemid=1

It’s very odd to describe David Hume and Immanuel Kant as Christian believers.

Roman law was an important sources of liberal ideas in European thought. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/medieval-political/#CivCanLaw

I agree with your thesis that European culture is not especially Christian but owes a lot to Greek philosophy, Muslim philosophy and science, and to original developments in European thought during the 17th and 18th centuries (prompted largely by the fact of bitter religious division). But the evolution of modern European thought was deeply influenced by Christianity at least in the sense that it was largely a critique of, or reaction against, the Catholic Church. That is one of the reasons why anyone wanting to understand modern European culture needs to study the middle ages.

Thanks for this. I agree about the significance of Bayle who was an important current leading to the Radical Enlightenment. Spinoza, however, goes further than Bayle in defending toleration and freedom of expression.

I did not describe Hume as a Christian, only as part of the mainstream Enlightenment. His skepticism led to radical conclusions with respect to revealed religion. But socially and politically, he stood on the conservative wing of the Enlightenment. I’m not sure what point you’re making about Kant. Certainly he was highly critical of organized religion, especially in works such as Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason, but his faith was clear.

It’s true there was no room in this essay to fit in a discussion of the Reformation, but I have written about it elsewhere and suggested that it was a far more ambiguous movement (or set of movements) than often credited:

I am not suggesting that Christianity was not important in the development of modern European thought, its development of notions of universalism being, for instance, highly significant. What I am suggesting is that much of what we think of as the ‘Christian bedrock’ of Western thought is not uniquely Christian and that the story is far more complex than the one usually told.

Pingback: Myten om det kristna Europa « Erik Herbertson

Thanks Kenan for this excellent post. I have 84 years as a born USA Catholic, 37 years as a Capuchin-Franciscan Friar, 25 years as an active priest among the campesinos and indigenous peoples of the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua and now 30 years in an Catholic valid marriage, father of two lovely daughters plus several foster daughters, and — I am still a strongly believing Catholic.

Now I’m working only half time (computer accounting) to keep the rice and beans on the table and the internet connection paid up to date, I finally have time to study and read.

Among the many interesting insights I found in your post was the Jewish vision of the Adam and Eve myth. I had always wondered about the deep silence of Jesus of Nazareth in the three Christian synoptic gospel accounts without a single reference to our “Christian” doctrine of “original sin.”

Now I wonder about where St. Paul in his letter to the Romans, Chapter 5:12, picked up “his vision” which obviously does NOT reflect your presentation of the Jewish vision despite Paul’s proud claim to have been raised as a strict Jewish Pharisee. St. Augustine of Hippo who died around the year 430 seems to have picked up Paul’s line of thought and left us Christians with a tremendously pejorative vision of us human beings from birth on.

The practical upshot of all this, is that it seems that today many believe we are “baptized” as Christians in order to wipe out our “inherited original sin” instead of recognizing baptism as a public sign of our commitment to the Life/Death Project of Jesus of Nazareth: the governance of his Father here on earth: “Our Father … thy Kingdom come on earth just as it is in heaven;” the building of that “other possible society” that “other possible world” not like the one we have made for ourselves where every four seconds one of our sisters or brothers dies from hunger, and our “Christian world” is still studded with wars for petroleum and geo-political maneuvering with millions of collateral civilian deaths besides the financing the onerous military/industrial complex heaped upon the backs of the common people. And at the same time we nonchalantly continue destroying by our greed the future of our grandchildren, our Own Dear Mother Earth.

Now that you’ve set me thinking Kenan, ¿have you anything to add in order that this old man might again enjoy a good night’s sleep?

Justiniano de Managua el 23 de nov. 2011

Thanks for this. My interpretation of Paul is, of course, that of an atheist not a believer. His importance is that he reworked the meaning of the crucifixion. Prior to Paul, the Jesus movement (there was, of course, no such thing as a ‘Christian’ then) had felt deeply humiliated by the betrayal, torture and execution of Christ. How could a Messiah whom they believed would deliver the kingdom of God have been left to die as a common criminal? Paul argued that the very nature of Jesus’ death, revealed the essential goodness of God. Jesus had been willing to die in such unspeakable fashion to atone for human sins, revealing an unconditional love for humankind.

In reworking the meaning of the crucifixion, Paul transformed a scandalous embarrassment into the defining symbol of Christian faith. But the obsession with the battered and bloody body of Christ created also, both in Paul’s writing and in much of subsequent Christian thinking, a morbid attachment to the righteousness of pain, on the one hand, and, on the other, a terror of the flesh and of worldly pleasures.

Paul’s interpretation of the crucifixion also raised the question: Why are humans so frail? Eventually, by the fifth century, the Church settled on an answer that was radically different from that of the Greeks and of the Jews: that of Original Sin. There are hints of this in Paul’s letters but, as you say, it was Augustine who fully fleshed it out. Here’s a post on Augustine and the early Christian debate on Original Sin and free will, an extract from my book on the history of moral thought.

The great question is: is Europe modern because of, or rather, in spite of, being Christian? Kenan seems to think it is the latter, I think it’s actually a combination of both. Some Christian elements inhibited the rise of modernity, but some other uniquely Christian elements (such as the doctrinal separation of Church and State, not mentioned in the essay) did contribute to modernity. At any rate, one must avoid the naturalistic fallacy. The fact that Europe has been traditionally Christian does not imply that it must continue being so. One may agree the horse was a great cause for progress and civilizational development; that does not imply we must still go around riding horses.

I am not suggesting that modernity happened despite Christianity. It would be absurd to suggest that given that Christianity has been the crucible within which European culture has developed over the past two millennia. All I am suggesting is that the story of European intellectual, social and cultural development is far too complex to be reduced to the simple narrative of Christianity as the bedrock of Western civilization.

I have written elsewhere about the Reformation. And my point is much the same as it is here: that the Reformation was a deeply contradictory movement, as reactionary as it was liberating.

Pingback: Linked and Loaded Brunch | Punditocracy