Review of Exodus by Paul Collier (Allen Lane)

Migration, Paul Collier observes ‘affects many groups, but only one has the practical power to control it: the indigenous population of host societies.’ So, he asks, ‘Should that group act in its self-interest, or balance the interests of all groups?’.

That question is at the heart of Collier’s new book which aims to reframe the immigration debate. Professor of Economics and Public Policy at Oxford University’s Blavatnik School of Government and co-Director of the Oxford Centre for the Study of African Economies, Collier has long been concerned with questions of poverty and justice. His previous book, The Bottom Billion, explored the reasons for the poorest nations of the world – containing a billion people – remaining so poor.

Collier brings the ‘bottom billion’ approach to the question of immigration, too. He dismisses the utilitarian argument that migration is a good because it helps ‘maximize global utility’ as ‘glib’ and too dismissive of those who lose out. Instead, Collier seeks to unpack the impact of immigration on three key groups – migrants themselves, the host community and, most importantly for Collier, those left behind in the countries of origin. Immigration affects each of these groups in different ways. The real question, he suggests, is not whether immigration is good or bad, but how much of it brings benefits to each of these groups, and how policy should balance out the rewards to and burdens upon each group.

Exodus is gracefully written and elegantly argued. But despite its wealth of statistical evidence, there is often a chasm between that evidence and Collier’s more contentious arguments. Many of its solutions are morally questionable.

Consider, for instance, Collier’s analysis of the impact of migration on those left behind. Two main factors are important here: the remittances sent back home by those who migrate, which are beneficial, and the brain drain caused by emigration, which is detrimental. For a handful of poor countries – in particular rapidly developing nations such as India, China and Brazil – the balance is in the black, particularly because the brain drain is actually a brain gain: those who migrate abroad often return home with improved skills, knowledge and education. For most poor countries, however, Collier suggests, the impact of the brain drain outweighs the benefits of remittances. Not just ‘countries that have been stagnant for decades’, such as Liberia, Sierra Leone, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Afghanistan and Laos, but also ‘more successful small developing countries’ such as Ghana, Uganda, Vietnam, Mauritius and Jamaica have ‘suffered net loses’. Such countries would ‘benefit from emigration controls’ to prevent their best people from leaving but in practice cannot ‘control either the emigration rate or the rate of return’, and so ‘are dependent upon controls set by governments of host countries.’

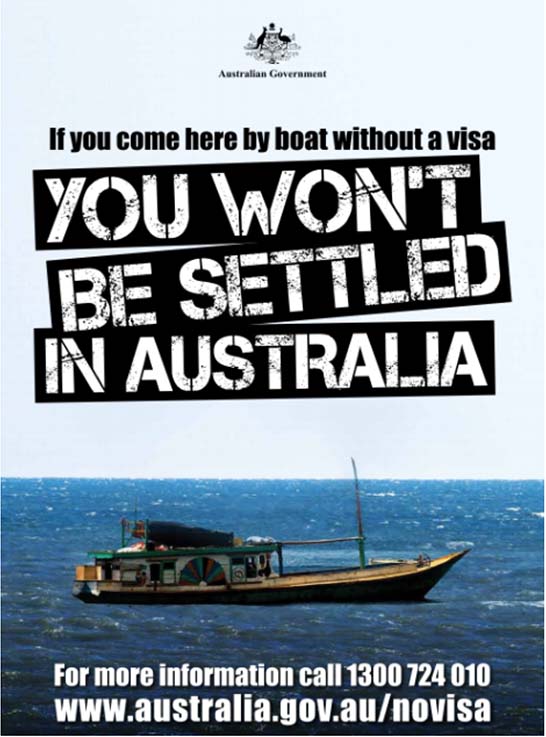

For Collier, then, there is a moral case for rich countries to impose immigration controls as a way of helping the poor. Suppose, though, that poor countries were able to prevent their citizens from leaving. Would it be moral for them to do so? I doubt that many people would say ‘Yes’. It would, after all, be asking such countries to behave like North Korea. But if it is immoral for poor countries to prevent their citizens from leaving, why is it moral for rich countries to do that job for them? Especially when to do so requires considerable coercion and brutality. The tragedy off Lampedusa this week, where more than 300 people may have drowned, revealed most starkly the human costs of establishing ‘Fortress Europe’. That fortress has been constructed through often the most odious means. For years, the EU paid huge sums to Libya’s Colonel Gaddafi for his security services to ensure that immigrants did not cross the Mediterranean. Today, Morocco’s equally vile security forces and detention centres play much the same role. And such policies and such consequences are not limited to Europe. From the injustices of the US drive against illegal Mexican migrants to the deployment of the Australian navy in its ‘stop the boats’ campaign against refugees, the enforcement of controls can be a very dirty business.

I am not suggesting that there may not be a moral case for immigration controls. But the claim that such controls are a means by which the rich can help the poor is so much moral hogwash.

‘It is not a satisfactory solution to Malian poverty’, Collier observes, ‘if its people should all become prosperous elsewhere’. That is true. But neither is it a satisfactory solution to Malian poverty to force its people to stay in Mali, whether through emigration or immigration controls. It is difficult to see how curtailing freedom of movement is a reasonable or rational response to the problems of global inequality.

Collier’s discussion of the impact of immigration on host countries is equally troublesome. He accepts that the economic fears about the impact of immigration are largely misplaced. But, he insists, too much diversity creates social problems, in particular by destroying ‘mutual regard’, the willingness to cooperate and to redistribute resources. He draws upon the work of the American sociologist Robert Putnam who has shown that the more diverse a community, the less socially engaged are its members – they vote less, do less community work, give less to charity, have fewer friends. Most strikingly, Putnam discovered that people in more diverse communities show greater distrust not just towards members of other ethnic groups but of their own, too. ‘It’s not just that we don’t trust people who are not like us’, Putnam observed. ‘In diverse communities, we don’t trust people who do look like us.’

Putnam’s work has long been seized upon by critics of immigration to suggest that diversity undermines the social fabric. The implications of the data are, however, far from clear. A key problem, as Putnam himself has pointed out, is that the study offers only a snapshot of attitudes at one moment in time. Diversity, though, is not a static phenomenon but changes over time, as does our political response to it. Over the past few decades, we have witnessed the demise of movements for social change, the rise of identity politics, the atomization of society, a loss of belief in universal values, all of which has led to civic disengagement and a greater sense of anomie. The real problem, then, may not be diversity as such but the political context in which we think about it.

Collier insists, however, on viewing political shifts almost entirely through the lens of diversity. Even the rise of free market policies in recent decades is shoved into this framework. According to Collier, the ‘policies of reduced taxation and increased reliance on the market’ that have marked the recent period may have been driven by ‘the pronounced increase in cultural diversity brought about by immigration’. Evidence? None. The closest to any evidence is the suggestion that ‘For example, the recent phase of open door in Britain has coincided with a collapse in willingness to fund redistribution.’ Even I know that coincidence is not the same as correlation is not the same as causation. It is not as if the political, social and economic reasons for the rise of free market philosophies and the attacks on state spending have not been exhaustively researched.

Perhaps nothing better reveals the problems of Collier’s approach than his discussion of the Mark Duggan case as an exemplar of what has gone wrong with immigration policy. Duggan was a young black man from London, a known criminal, who was shot dead by Tottenham police in August 2011. In response, local people organized a protest outside the police station, a protest that turned violent, and came to spark off riots in London, and nationwide.

The details of the Duggan case remain unclear. There is currently an inquest into his death that might throw more light on matters. The police have acknowledged that Duggan had not, as first claimed, fired at them. The lawyers for the Duggan family have questioned whether he was even holding a gun. The only thing that seems certain is that Duggan was shot by a policeman.

Now read the story as Collier tells it: ‘Two policemen arrest a known criminal with previous convictions. In the car taking him to the police station the criminal pulls a gun; the police are also armed and shoot him dead.’ In response ‘the social network of the criminal rushes to the police station and mounts a protest, several hundred strong, against the police’.

Not only is this factually inaccurate (Duggan, for a start, was shot outside the car not inside), and accepts as given fact that which is in dispute (for instance, that Duggan pulled a gun) but the very language suggests that Collier is searching primarily for a narrative to bolster his argument about immigration. This may be acceptable in a polemic, but in a book in which the author stresses again and again the importance of evidence and the dangers of too quickly jumping to conclusions, it appears an odd approach.

Collier then compares the Duggan case to an incident from the 1960s, in which a criminal shot dead three policemen. He was ostracized by his ‘social network’ for breaking a social norm accepted even by criminals that firearms should not be used. Forced to flee London, he was soon apprehended. (Collier does not name the criminal or provide any further details of the case.)

The two incidents, as Collier himself acknowledges, are not comparable. In one case a criminal shot three policemen. In the other the police shot dead a suspect. That, however, does not prevent Collier from speculating that the difference between the response of the criminal community in the 1960s and that of the anti-police protestors half a century later may be the result of the transformation of norms brought about by immigration. A ‘salient difference’ between the two cases, he suggests, ‘is that Mark Duggan is Afro-Caribbean and that the crowd of protestors that assembled outside the police station was also Afro-Caribbean.’ ‘The bonds between Afro-Caribbean people’ were stronger than ‘any sense that in possessing a gun he had breached a taboo’. Perhaps the Tottenham protestors responded as they did because of their experience of racist policing in the area, the history of which has been well documented? No. According to Collier ‘the bonds between Afro-Caribbean people’ ensured that ‘members of Duggan’s social network responded to the news by presuming that the police had shot him unnecessarily, rather than, what is a more likely interpretation of events, that the police officer reacted to an immediate situation of extreme fear’. Why is it a more likely interpretation? Perhaps because it better fits the narrative Collier wants to tell. One does not have to view the killing as a racist incident, or even to accept that the police necessarily acted inappropriately, but surely one needs a greater degree of scepticism and open-mindedness than Collier reveals here?

Collier acknowledges that the riots that followed were not racially motivated. But, he insists, they reflected ‘a decline in social capital within the indigenous population’ caused by immigration having led to ‘indigenous people [losing] trust in each other and so [resorting] to opportunistic behaviour’. Again, where is the evidence that such loss of social capital is specifically the result of too much immigration? None is produced.

Throughout the book, Collier chastises other participants in the immigration debate for allowing their prejudices to shape their reasoning. He draws upon the work of psychologist Jonathan Haidt to suggest that in most policy discussions, especially over immigration, ‘moral judgment shapes [peoples’] reasoning rather than the other way round’. ‘We grasp at reasons’, he argues, ‘and pull them into service to legitimize judgments that we have already made on the basis of our moral tastes’. His aim in writing Exodus, he insists, is to follow a different approach, one that does not ‘politicise’ migration ‘before it has been analyzed’. I am at a loss, though, to know how to describe Collier’s analysis of the Duggan case, as of much else in this book, as anything other than pre-judged, a narrative honed to fit not the facts but an already established argument.

Collier concludes the section on Duggan and the riots by suggesting that ‘working from anecdote… is not a valid form of analysis’ but is rather ‘the stuff of opinionated advocacy’. Using anecdotes, ‘we could stack up whatever apparent support for whatever story we find appealing’. Therefore, he insists, ‘the purpose of the above anecdotes [about Duggan, the riots, etc] in which immigration appears to have undermined social capital, is decidedly not to strengthen an argument’. One has to admire Collier’s chutzpah, but it is difficult to see what role his anecdotes could play but as a prop for his argument.

Collier’s policy prescriptions are as questionable as his analysis. A key argument in Exodus is that the levels both of migration and of problems created by it are linked to the size of diasporas. If there are already large populations of Jamaicans or Bangladeshis in a country, then it is easier for more Jamaicans or Bangladeshis to arrive because the costs of migration are reduced. At the same time, a sizeable diaspora slows down integration because it becomes more comfortable to live in enclaves. A vicious cycle, therefore, develops: a large diaspora draws in more fellow-immigrants, which hinders integration, which makes the diaspora larger, which draws in more fellow-immigrants, and so on. The result, in Collier’s view, is an inevitable acceleration of immigration in coming years to ‘epic proportions’.

It is a contentious argument, not least because it ignores the policy prescriptions that shape relationships between social groups and hence the size of diasporas and the nature of integration. Collier’s solution is equally contentious: he wants to peg immigration from any particular group to the size of the already existing diaspora, a policy that appears neither practical nor moral.

Collier thinks that immigrants’ right to bring in relatives should be cut, partly because it ‘reduces the incentive to make remittances’ (another disingenuous ‘we are only doing it for your benefit’ claim) and partly because indigenous workers do not possess the same right (well, no, they don’t, primarily because their families are mostly here). Any refugee who flees a war, Collier insists, should be sent back the moment the conflict ends. And so on.

The tragedy at Lampedusa demonstrates again most forcefully the need to rethink immigration policies and their moral implications. Collier’s book has been welcomed as a ‘humane’ and ‘rational’ intervention in an often toxic debate. That, it seems to me, tells us more about the character of the contemporary immigration debate than it does about the merits of Collier’s arguments.

A shorter version of this review was published in the Independent.

The photos are of Mexicans trying to enter the USA (AP Photo/ Lenny Ignelzi) and of an immigration detention centre in Greece (UNHCR / L Boldini). The cover image is ‘Hold On’ by J. from the Refugee Art Project.

It is not immoral to refuse to allow one’s First World country to devolve into a Third World country.

“Putnam’s work has long been seized upon by critics of immigration to suggest that diversity undermines the social fabric…. Over the past few decades, we have witnessed the demise of movements for social change, the rise of identity politics, the atomization of society, a loss of belief in universal values, all of which has led to civic disengagement and a greater sense of anomie. The real problem, then, may not be diversity as such but the political context in which we think about it”

What the author calls “political context” sounds a lot like the undermining of the social fabric he’s trying to explain away.

Replying to myself: “explain away” seems a bit harsh here. But there does seems to be some question-begging in this part of the article about what counts as the undermining of the social fabric and what counts as mere “political context”.

Mercher, what I am questioning is not whether or not the social fabric has eroded. It is whether immigration is responsible for any such erosion. Greater civic disengagement is, as I pointed out, a real social development that needs addressing. But the roots of such disengagement lie, in my view, not in immigration but in a wider set of social changes – the demise of movements for social change, the rise of identity politics, the atomization of society, a loss of belief in universal values, etc.

Are there rigorous impact evaluations in this field? It would be good to arm the various arguments with quantifiable evidence on the effects of immigration. Although very tough to do, and even then I’m not sure how useful it would be, it could still be better than the current debate based on anecdote.

You’re making a distinction between “Greater civic disengagement” and “the demise of movements for social change etc.” But again, these really do sound like the same thing.

Some people say that A causes B. You disagree (and you may be right) but to say that in fact B causes B isn’t a convincing counterargument.

If it were the case that ‘greater civic disengagement’ and the ‘demise of movements for social change’ referred to the same phenomenon, then it would make my argument even more forcefully. After all, few would imagine that immigration has been responsible for the demise of movements for social change. Most would accept that there are underlying political causes.

As it happens the two are not the same. To talk of the strength of civil engagement is to talk of the health of civil society. Engagement in civil life can take many forms from helping out at a charity shop to joining a parent teachers’ association to taking part in trade union activity. Movements for social change are important because they link civil engagement to a wider project for social and political change and help transform ideas of, and forms of, social solidarity. Erosion of such movements has also frayed civil society and reduced civil engagement. Is it not plausible, I am asking, that in that process it may also have helped reshape our conceptions of diversity?

The conceptual distinctions you’re trying to make between things like “civil engagement” and “movements for social change” seem purely verbal ones to me. They don’t correspond to how actual people might think about these things.

The way people feel about their neighbours affects their sense of solidarity with wider society and therefore how they vote or whether they choose to get involved with social movements. This seems to me to be a straightforward fact. If you think that “few would imagine” this, I can only suggest that you talk to more people.

And sure, it’s also plausible that political changes have “helped reshape our conceptions of diversity”. In fact, I think it’s almost certainly true that everything we might talk about here is thoroughly mixed up with everything else. But simply picking one plausible connection out of this causal hairball and offering it as a counterargument to the existence of another plausible (and, in fact, evidenced) connection and then moving swiftly on (“The real problem then…”) is not a good argument.

You write that ‘the way people feel about their neighbours affects their sense of solidarity with wider society and therefore how they vote or whether they choose to get involved with social movements’. True. But what affects ‘the way people feel about their neighbours’? You seem not to understand that this is the real debate.

You claim that the Putnam / Collier argument is ‘evidenced’. What is it that is evidenced? Putnam has shown that in a particular society at a particular historical moment greater diversity is correlated with greater civic disengagement. Note: he has not shown that one is caused by the other. Many critics of immigration have seized on the Putnam data to suggest just such a causal link: that greater immigration/diversity creates civic disengagement. That may be the case, but the Putnam data does not show that. I am suggesting an alternative interpretation of the data, one that does not look at the impact, and perception, of diversity at one moment in isolation but places it into historical context. You, like Collier, seem to take the way that people feel about diversity as a given. In fact it changes historically, and it changes historically because it depends upon the political context. It is the lack of historical context that is the real problem with the immigration debate, a point I have detailed many times.

Thanks for this review. As I recall, Collier has a little bit of a reputation for clever superficiality in less-ideological international development circles… (Or maybe that’s just my own superficial take on his Bottom Billion!)

In any case, you seem to be suggesting that his argument for immigration controls comes down to the (1) brain drain and (2) the loss of solidarity due to diversity.

As to (1): does Collier also consider the potential for brain waste (i.e., the inability of origin countries to properly exploit their human resources due to lack of other resources)–not just as a problem of economic inefficiency but also as a potential source of political turmoil (since the lack of professional outlets might lead idle but ambitious students to favor radical political change)?

As to (2): here is a (perhaps more) salient empirical study that reaches the opposite conclusion: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1747-7093.2006.00027.x/abstract. Also, does Putnam’s work focus only on the SHORT-term loss of solidarity due to diversity?–Because, if so, obviously, one could argue that the LONG-term benefits of diversity might outweigh its short-term costs… (Besides, I wonder whether Collier would also, by analogy, conclude in favor of imposing birth control on account of some combination of the pain of childbirth, the anxieties of parenthood, the dilution of resources, etc. Perhaps there are more things in Morality than are dreamt in his economics.)

I haven’t yet finished reading Prof Collier’s book, but I’ve read his discussion of how ethnic diversity reduces social cohesion. I’m not in a position at this point to dispute Collier’s facts (I was already familiar with the argument that diversity correlates with weaker support for social welfare, for example, and this seems to be a drawback that we just have to deal with). But I don’t understand how his argument couldn’t also be an argument in favor of such odious policies as “separate but equal” racial segregation. If so, then I submit there is such a thing as social cohesion at too great a cost.

It is convenient for Collier that he acknowledges that immigration of the poor to the rich world has been by and large good up to this point. His suggestions that more immigration will tear asunder the social fabric of the rich world despite the lack of historical examples thus seems heavy on doomsaying and light on falsifiability. The obvious thing to do would be to compare rich nations that have been more permissive to immigration to those that have been less permissive. He does frequently mention that the more permissive America seems to be better at integrating immigrants than less permissive European nations, but he waves this inconvenience aside with a question-begging remark about American identity being “rooted in the welcoming of strangers”, unlike European identity which is based on nationhood. Perhaps this just means Europeans could stand to learn something from Americans about welcoming strangers?

“I don’t understand how his argument couldn’t also be an argument in favor of such odious policies as “separate but equal” racial segregation”

I don’t see how that would be implied – surely that’s about as un-cohesive as a society gets.

Also worth critiquing is the unethical asymmetry of globalisation in this context. We are happy to benefit from cheap foreign labor, commodities and produce flowing freely across borders. Indeed the West insists upon it, often via embargoes or military action. We’re happy, in short, to bleed foreign countries when it suits us, and turn our backs otherwise, even though many of the foreign problems that trigger immigration, are a direct result of our foreign interventions.

Global capitalism is profoundly unjust, and our economists are for the most part nothing more than a cabal of dogmatic purists, ceaselessly bending the narrative to support the status quo of growth and consumerism. Paul Collier is a case in point. It should be telling that he is, by far, one of the most progressive and socially concerned economists. These days that is a bit like being a pacifist executioner.

Excellent points, and I enjoyed the review. Thank you.

I haven’t yet read Exodus so these comments are based on others’ readings. Your points on the book’s treatment of Mark Duggan are very good. But, these aside, one clear fact that Collier seems to overlook (and you?) is that Duggan was mixed race.

Choosing to define him as ‘Afro-Caribbean’ reflects the very assumptions about race and immigration (and criminality) that Collier purports to transcend through his marshalling of ‘evidence’. Using the response to Duggan’s death at police hands as evidence of immigrant ‘social networks’ that tear at the fabric of the ‘host’ country is at best spurious.

If we are looking for evidence, what could be simpler than looking at the family and friends who gathered for Duggan’s funeral or attended recent court hearings. They were dark brown and pale pink and many shades between. This is what many families in Britain look like now. How does Collier’s thesis accommodate this fact? From reviews I’ve read, it can’t: the facts don’t fit the theory.

Britain today, after several waves of mass migration in living memory, is far too complicated for simplistic notions such as ‘host’, ‘indigenous’ and ‘immigrant’. From what I can tell Duggan was born and raised here. He was no guest. One of his parents was ‘indigenous’. So why is Duggan used to embody unproblematically the dangerous legacy of immigration? And if neither birth in a given nation nor ‘indigenous’ ancestry qualifies one as indigenous, what does?

I’m happy to be proved wrong – but might it be looking like what a particular observer thinks an indigenous person should look like, rather than what that observer thinks an Afro-Caribbean immigrant looks like?