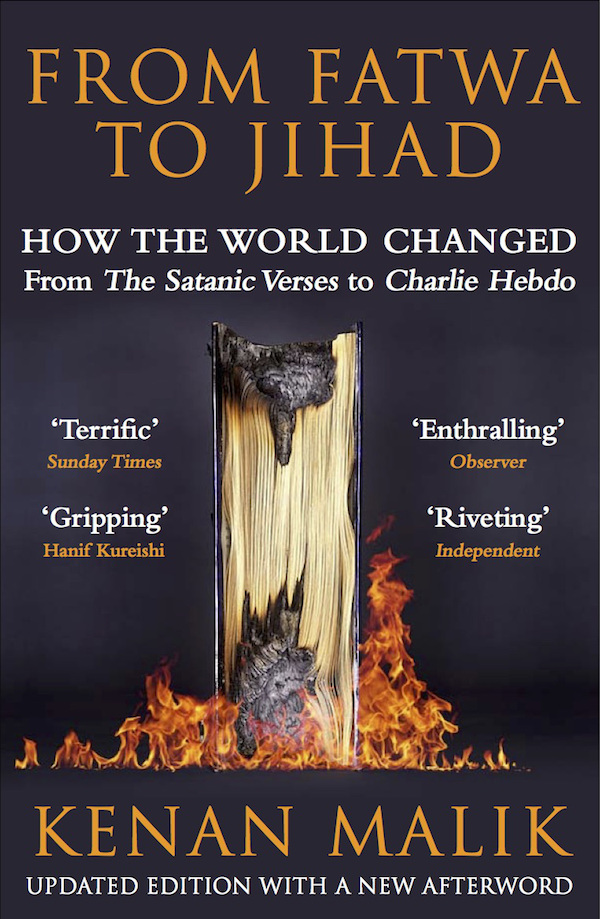

This is an extract from the Afterword to the new edition of my book From Fatwa to Jihad: How the World Changed From The Satanic Verses to Charlie Hebdo. This extract looks at the free speech debates around the Danish cartoons and Charlie Hebdo. You can buy the book from most bookshops, or from Amazon or from the Book Depository.

In December 2009, about nine months after From Fatwa to Jihad was first published, Index on Censorship, one of the world’s foremost organizations for freedom of expression, published in its journal an interview with the Danish-American academic Jytte Klausen about her book on the Danish cartoon controversy, The Cartoons that Shook the World. Shortly before publication, the publishers, Yale University Press, took the unexpected decision to remove all the cartoons from the book. The interview explored that decision, and why Klausen disagreed with it

Klausen’s book, like all academic books, had been reviewed by a number of scholars, each of whom was asked about the cartoons, and all of whom insisted that they should be included. Yale University Press’s publication committee also accepted the inclusion of the cartoons. Then the university took advice from ‘security experts’, including John Negroponte, the director of National Intelligence under President George W Bush. On their advice, at the last minute, Yale University Press decided to pull not just the cartoons but also all historical images of Muhammad from the book.

‘I said that they were wrong-headed, they misread the conflict,’ Klausen told the editor of Index on Censorship, Jo Glanville. Yale University Press used Klausen’s own data from her book to justify censoring the cartoons. Linda Lorimer, Vice President of Yale University, told Klausen, ‘Here is your table that shows that the cartoons caused over 200 deaths’. But, observed Klausen, ‘in my book I write very clearly these deaths were not caused by the cartoons, but were part of conflicts in pre-existing hot spots [such as] northern Nigeria, where there’s a civil war between Muslim Salafists, sharia courts, trying to push out Christians. The whole point of the book is that the cartoon conflict has been misreported as an instance of where Muslims are confronted with bad pictures and spontaneous riots explode in anger. That is absolutely not the case. These images have been exploited by political groups in the pre-existing conflict over Islam.’

Nor, Klausen insisted, was there a security threat. ‘There has not been a single angry email, fax, phone call from anybody Muslim. Yale University has not produced any threatening letters, I have not received any threatening letters, the press has not received any.’ ‘It’s highly ironic’, Klausen pointed out, ‘that by this act of censorship on the part of Yale, they have turned my book into another chapter of this fruitless debate – and have in fact made it a symbolic issue.’

The real irony, however, was yet to come. Index on Censorship, having published an interview about the irrationality of Yale University Press censoring the cartoons, and of the negative impact of that decision both on free speech and on perceptions of Muslims, then refused to publish any of the cartoons to illustrate the interview in its own magazine. The decision, taken by the board against the wishes of the editor, was extraordinary – one of the world’s leading free speech organizations censoring itself, in an article about why such censorship was wrong. It was especially extraordinary as the reasons given for not publishing the cartoons were exactly the same as those given by Yale University Press and shredded by Klausen in the interview – that there was a danger of violence and that publishing the cartoons was ‘unnecessary’ and would have been gratuitous.

I was at the time a board member of Index on Censorship – and the only one who publicly objected to the decision. ‘Index on Censorship has in recent years chronicled many instances of what we’ve called “pre-emptive censorship”’, I wrote in an open letter, ‘the willingness to censor material because of fear either of causing offence or of unleashing violence.’ There was a ‘depressingly long’ list of publishers and theatres and art galleries censoring what was regarded as ‘offensive material’. It was ‘both disturbing and distressing to find Index on Censorship itself now on that list’. The authority of Index on Censorship in its free speech campaigns, I concluded, ‘rests largely upon its moral integrity’. In refusing to publish the cartoons, Index was ‘not only helping strengthen the culture of censorship’, it was ‘also weakening its authority to challenge that culture’.

What is true of Index on Censorship is true also of liberal societies more broadly. The moral force of a liberal society depends to a large degree upon its integrity in upholding basic liberal values. Failure to do so inevitably undermines its authority. One of the key themes of this book has been how, in the years following the Rushdie affair, Western liberals came to internalize the fatwa, to adopt what one might call a moral commitment to censorship; the belief that because we live in plural society, we must police public discourse about different cultures and beliefs, and constrain speech so as not to give offence. In the words of the British sociologist Tariq Modood, ‘If people are to occupy the same political space without conflict, they mutually have to limit the extent to which they subject each others’ fundamental beliefs to criticism.’

The willingness of Western liberals to accept censorship in the name of pluralism has not simply helped strengthen the culture of censorship in Western societies and beyond, it has also weakened the authority of Western societies to challenge illiberal sentiments. Perhaps no event has been more revealing of the failure of liberals to stand up for liberal values than the Charlie Hebdo killings.

* * * *

A few days after the shocking attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris in January 2015, I was interviewed by the BBC. ‘Don’t you think’, the interviewer asked, ‘that the degree of solidarity expressed towards Charlie Hebdo represents a turning point in attitudes to free speech?’ ‘I doubt it,’ I replied. ‘There may be expressions of solidarity now. But fundamentally little will change. If anything, the killings will only reinforce the idea that one should not give offence.’

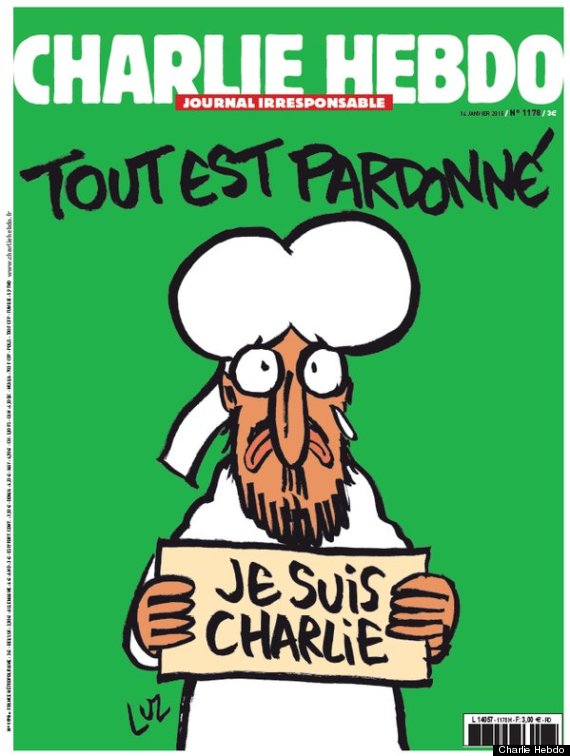

Shock and outrage at the brutal character of the slaughter led many in the immediate aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo killings to close ranks with the slain. ‘Je Suis Charlie’ became the phrase of the day, to be found in every newspaper, in every Twitter feed, and in demonstrations in cities across Europe. Four days after the attack, more than a million people, and forty prime ministers and presidents from around the globe, marched through the streets of Paris in solidarity with the magazine.

None of this changed underlying attitudes to free speech, nor challenged the idea that in a plural society we ‘mutually have to limit the extent to which we subject each others’ fundamental beliefs to criticism’. The degree to which Western liberals have come to accept the moral commitment to censorship was revealed by Mary-Kay Wilmers, editor of the leftwing London Review of Books, who, in reply to a letter that that had expressed ‘deep disappointment’ at the LRB’s lack of response to the Charlie Hebdo killings – ‘No message of solidarity, no support for freedom of expression’ – wrote, ‘I believe in the right not to be killed for something I say, but I don’t believe I have a right to insult whomever I please.’

That, of course, was the argument made by critics of Salman Rushdie. Shabbir Akhtar, the philosopher who became spokesman for the Bradford Council Mosque’s campaign against The Satanic Verses, wrote that ‘self-censorship’ was important because ‘what Rushdie publishes about Islam is not just his business’ but also ‘every Muslim’s business’. It was immoral to defend in the name of freedom of expression ‘wanton attacks on established religious (and humanistic) traditions’.

The discussion about Charlie Hebdo showed how ideas and arguments that twenty-five years ago dwelt largely in the margins now occupied the mainstream. Hardly had news begun filtering out about the Charlie Hebdo shootings, than there were those suggesting that the magazine was a ‘racist institution’ and that the cartoonists, if not deserving what they got, had nevertheless brought it on themselves through their incessant attacks on Islam.

This time, unlike in its response to the Danish cartoons, Index on Censorship laudably insisted that ‘Freedom of expression is non-negotiable’ and called ‘on all those who believe in the fundamental right to freedom of expression to join in publishing the cartoons or covers of Charlie Hebdo’. But many others, including many organizations promoting free speech, took a very different stance, unwilling even to show solidarity with the slain cartoonists and journalists.

Perhaps the most disgraceful refusal of solidarity came with the boycott in 2015 by a host of writers – including Peter Carey, Michael Ondaatje, Teju Cole, Rachel Kushner and Geoff Dyer – of the annual gala of PEN America in protest against the organization’s decision to award Charlie Hebdo its annual Freedom of Expression Courage Award. PEN America, part of PEN International, is an organization of writers which describes itself as ‘champion[ing] the freedom to write, recognizing the power of the word to transform the world’. The Courage Award was established to ‘honor exceptional acts of courage in the exercise of freedom of expression’.

For the critics, it was the very courage of journalists and cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo in refusing to be bowed by the deadliest of threats that was the problem. The willingness of the magazine to challenge, to provoke, to ridicule Islam was, in the words of one of the boycotters, Rachel Kushner, an expression of ‘cultural intolerance’. Meanwhile Australian novelist Peter Carey placed upon Charlie Hebdo all the weight of France’s relationship with its Muslim citizens, criticizing ‘PEN’s seeming blindness to the cultural arrogance of the French nation, which does not recognize its moral obligation to a large and disempowered segment of their population’.

The debate over Charlie Hebdo encompasses so much more than the magazine itself. But first we have to understand something about the magazine. Charlie Hebdo was a child of May 1968. It was founded in 1970 after its predecessor, Hara-Kiri, was banned for making fun of Charles de Gaulle on the occasion of his death. It was a magazine of the anarchic left, brimming, in the words of journalist Leigh Phillips, ‘with insolence and bile for capitalist, governmental and clerical elites’. Its closest British equivalent would be Private Eye, with its mixture of cartoons and investigative journalism. But Charlie Hebdo was far more radical and more willing take risks, as well more puerile in its humour, than Private Eye.

The magazine bursts with vitriol for all forms of elites, whether economic, political or clerical. But it is Charlie Hebdo’s hostility to religion, and in particular its willingness to treat Islam in the same way as it treats other religions, that most enrages its critics. The French left has, from the Revolution on, been defined by its anti-clericalism, but the context of that anti-clericalism has changed enormously over the past three centuries, and has shaped the relationship of the left with different religions.

The modern French Republican tradition emerged in part through a bitter struggle with the Catholic Church. Provoking the Church and offending Catholicism was, and is, seen as a necessary part of the progressive tradition. The power and influence of the Church has, however, long since declined. Many Catholics may feel aggrieved at the mocking of priests or the Pope, but these days such mockery carries little political charge.

France’s relationship to Judaism has been shaped by the centrality of, and subsequent guilt about, anti-Semitism. From the Dreyfus affair to the Vichy regime, anti-Semitism has played a critical role in French national life. Consciousness of that history has established certain lines that cannot be crossed. The denial of the Holocaust is a criminal offence under French law – an acknowledgement that guilt about the history of anti-Semitism trumps any attachment to free speech. Writers and cartoonists are far less willing to mock Jews or Judaism than they are Catholics and Christianity or Muslims and Islam. This was true of Charlie Hebdo itself. The magazine was often accused of anti-Semitism, both for its caricatures of Jews and for its criticism of Israel. But the case of cartoonist Siné suggested that a degree of restraint or self-censorship was not evident in other areas. In 2008, Maurice Sinet, who worked under nom de plume Siné, wrote in a column about rumours that President Nicolas Sarkozy’s son was to convert to Judaism prior to marrying an industrial heiress. ‘He’ll go a long way in life, that little lad’, Siné joked. He was prosecuted for incitement to racial hatred, for allegedly linking Jewishness to financial success. The courts dismissed the case. Nevertheless, Siné was sacked by Charlie Hebdo.

In recent years, French anti-clericalism has found a new target in Islam. However, Islam plays a far more complex role in French society than Catholicism once did, and its place in Republican consciousness is, in many ways, closer to that once occupied by Judaism. Islam acts as a deeply conservative force within France’s North African communities that remain predominantly secular. At the same time, as I have suggested earlier, politicians and commentators have increasingly presented Islam as an existential threat to French values and identity while also insisting on labelling the predominantly secular, and diverse, North African population as ‘Muslim’. The consequence has been to create the perception that North African communities are not really part of the French nation, and to justify discrimination against them.

The willingness of Charlie Hebdo to mock Islam, even as Muslims are the objects of hatred and discrimination, has led many to denounce such mockery as racist, in much the same way as many denounced Salman Rushdie for his ‘blasphemies’ in The Satanic Verses. There are many things of which one can reasonably accuse Charlie Hebdo: that it is puerile, perhaps, or naive or too obsessed with anti-clericalism, and often not very funny. Many feel that it has lost its way in recent years, that it is no longer as radical as it once was. Leigh Phillips suggests that in the wake of 9/11, ‘the editor at the time, Philippe Val, took a “clash of civilizations” turn that infused the paper’. What one cannot reasonably do is damn it as racist.

On many issues I disagree profoundly with Charlie Hebdo’s editorial line. Like many on the left in France, Charlie Hebdo is strongly drawn to the policy of laïcité. ‘Laïcité’ is usually translated as ‘secularism’. It is, however, as a secularist that I oppose it. Secularism demands a separation of state and faith. Laïcité, on the other hand, refers to a form of state-enforced hostility to religion. It requires the state to intervene in matters of faith. Support for laïcité is not, however, an expression of racism, any more than opposition to it is a mark of anti-racism. People can in good faith argue about the merits of laïcité. What one cannot argue in good faith is that Charlie Hebdo is a ‘racist institution’.

Charlie Hebdo is fiercely hostile to Islam. It is also fiercely hostile to policies that discriminate against migrants and minorities, from opposing the DNA testing of migrants to challenging the demonization of the Roma to excoriating the European Union’s treatment of refugees. It is a record that would stand up well against that of many of the critics who denounce the magazine as ‘racist’.

Nor is Charlie Hebdo as obsessed with Islam as many of its critics suggest. The newspaper Le Monde scrutinized every Charlie Hebdo cover from January 2005 to January 2015. Of the 523 covers in a ten-year period, just seven were linked specifically to Islam; three times as many targeted Catholicism.

One of the cartoons that attracted most criticism was one drawn by the editor Stéphane Charbonnier. It depicted a black woman’s head on a monkey’s body next to a stylized red, white and blue flame that is the logo of the far-right Front National. The headline read ‘Rassemblement Bleu Raciste’ or Racist Blue Rally. The woman in the cartoon was a caricature of the then justice minister, Christiane Taubira, while the headline is a reference to the FN slogan ‘Rassemblement Bleu Marine’, a play on the name of their leader, Marine Le Pen. The Front National had recently compared Taubira to a monkey, publishing a photograph of a baby monkey with the words ‘At 18 months’ next to a picture of Taubira captioned ‘Now’. The cartoon was not a racist assault on Taubira, but a condemnation of the Front National’s racism. Taubira has, in fact, been one of the keenest defenders of Charlie Hebdo, giving a moving oration at the funeral of one of the slain cartoonists, Bernard Verlhac, who drew under the pen name Tignous. Taubira paid tribute not just to Tignous but to all those slain: ‘Journalists, cartoonists, economist, psychoanalyst, proofreader, guards – they were the sentinels, the watchmen, the lookouts even, who kept watch over democracy to make sure it didn’t fall asleep. Constantly, relentlessly denouncing intolerance, discrimination, simplification. Uncompromising.’

Yet in the debate about Charlie Hebdo that followed the January slaughter, its critics continually republished this cartoon as evidence of the magazine’s racism. It could be that the critics, most of whom were not French, did not understand the context of the cartoon. Equally likely, however, was that the context simply did not matter to them. For, paradoxically, despite the hostility to the cartoons, the cartoons themselves were immaterial to much of the criticism.

Consider, for instance, two cartoons that Charlie Hebdo published in September 2015. It was the height of the ‘migration crisis’ in Europe, when the arrival of tens of thousands of migrants, and the failure of the Europe Union adequately to respond, spawned major political tensions. The death of Aylan Kurdi, a two-year-old Syrian refugee whose body was found washed up on Turkish beach, generated shock and revulsion worldwide.

One of the cartoons depicted a Jesus-like figure walking on the water, ignoring a drowning child. ‘Christians walk on water,’ the text read, ‘Muslim children sink’. The carton was captioned ‘Proof that Europe is Christian’. The second cartoon showed an Aylan Kurdi-like toddler face-down on the shore beside a McDonald’s-style billboard offering two children’s meal menus for the price of one. ‘So close to making it . . .’ ran the caption.

The cartoons were clearly ridiculing Europe’s pretensions to be a Christian continent, and its obsession with consumerism and indifference to migrants’ lives. An accompanying editorial denounced Europe’s ‘hypocritical response’ to the migrant crisis and compared that response to attitudes towards Jews fleeing Nazis.

Yet, many insisted on seeing the cartoons as mocking, not Europe’s response but the migrants themselves. ‘Aylan Kurdi’s death mocked by Charlie Hebdo’ read the headline in the Toronto Sun. According to Britain’s Daily Mirror, ‘Charlie Hebdo publishes cartoons mocking dead Aylan Kurdi with caption “Muslim children sink”’. Thousands took to social media to denounce the magazine as racist. Britain’s Society of Black Lawyers even threatened to take Charlie Hebdo to the International Criminal Court for ‘incitement to hate crime and persecution’, its chair Peter Herbert claiming that the magazine ‘is a purely racist, xenophobic and ideologically bankrupt publication that represents the moral decay of the French nation’.

All this suggests that the actual cartoons in Charlie Hebdo were irrelevant to the campaign against the magazine. It is, rather, what Charlie Hebdo symbolizes as an institution that infuriated its critics. Its real crime was not racism but its challenge to what has become an unbreakable commandment for many contemporary liberals: ‘Thou shalt not cause offence.’

The cover image is by the French artist and illustrator Maumont.

Trivial comment: “to stand up to liberal values”; I think you mean “to stand up FOR liberal values”

Splendidly put. And the self-censorship, and the willingness to censor others, that you so rightly deplore seems to me to be linked to the cult of victimhood, with its censorious condemnation of what it calls “microaggressions” and “cultural appropriation”.

There is a place for what I might call rhetorical self-censorship. Foolish, for example, to link defence of evolution science to attacks on religion. Foolish, likewise, to introduce criticism of Muhammad’s private life into a discussion intended to persuade Muslims to liberalise the treatment of women. So how does one draw the line between such common-sense restraint, and the morally corrupt self-censorship that you so properly condemn?

I think the distinction is that the one case, you are making the judgement for yourself to avoid expressing certain incendiary arguments or ideas in the interests of your rhetorical purpose or even just good taste. Whereas in the other, your right to express yourself is being suppressed by a culture which condemns your views as “offensive” and thus unfit for discussion. In the former case you are making the decision for yourself based on your own discernment, but in the latter you are being forced to conform to the sensibilities of other people.

I would dearly love to buy the book. Unfortunately, it is still not available for sale in India.

Thank you, I found this interesting and will look to get a copy of your book.

I agree that the disjunct between ‘Nous sommes tous Charlie’ and the banning of controversial speakers on campus (for ex.) is certainly striking. People are happy to uphold freedom of speech when it suits them…

And I agree that we should be able to make the difference between printing items liable to give offence when it is for informational rather than offence-giving purposes. Such as the reprinting of the Danish cartoons, or even (from my university experience) the printing of racial slurs in an academic paper about the philosophy of racial slurs.

But then, I also think we should be able to say that deliberately giving offence is simply unkind and thus wrong. You might have the freedom to do so and we might uphold that freedom by not advocating for legally or institutionally enforced censorship, but I also want to feel free to say that, morally, it really should be the case that thou shalt not give offence. Why would a decent person want to? – has always been my question.

You miss the point, twice. Firstly, if I am never to give offence, then I am never free to speak my mind. Biblical creationists, for example, are offended (and I am proud to say, have attacked me publicly by name) by what I have to say about their mangling of science and religion. Secondly, there is a huge difference between what one (or perhaps every) decent person might regard as wrong, and what, if anything, should be suppressed.

Thanks, I don’t think I’ve missed the point though.

Firstly, I think we can distinguish between giving offence and taking offence. I don’t think it’s decent to deliberately give offence. If you say that Biblical creationism is inconsistent with science (or whatever) and someone finds themselves offended by that, that is a different thing. I haven’t advocated making *the taking of offence* as the deciding factor in whether a statement is morally decent or not.

Secondly, I haven’t advocated for any (legal) suppression of statements deliberately intended to give offence. I have simply pointed out something that often goes unmentioned in these debates, which is that not every exercise of a right is necessarily a decent action. Again, I think it’s perfectly possible to maintain the distinction between having the right to do something, and it being morally decent to do that thing.

In reverse order: what is being challenged here is the presumption, which you share, that the giving of offence, incidental or deliberate, is an indecent thing to do. The whole point is that self-censorship to avoid giving offence is pernicious. And I am perfectly well aware that my writings on creationism and creationists cause offence to biblical creationists. I can even imagine circumstances in which I would actively set out to do so, if their propensity to take offence was relevant to my argument. Ridiculing of others’ deeply held beliefs is bound to give offence, and at times the degree of offence taken, is itself Exhibit A.

As I said in my first comment on this post, these are rhetorical, not moral, decisions, and to regard even the gratuitous giving of offence as a moral issue is bound to lead to the kind of self-censorship that Kenan so rightly deplores.

I think an important thing to remember here is that we are talking about giving offense in the context of public discussion and debate. I agree with you inmywritemind that when you are around people you know personally, like your close friends, decency demands you respect their feelings and sensibilities and not deliberately say things to cause offense.

But in the public sphere, as Braterman said this guideline just doesn’t seem to make sense anymore. Anything you say is guaranteed to aggravate someone out there, and there is no objective way to separate who it is okay and who it is not okay to offend. If you have an idea or opinion that you believe needs to be discussed and considered, or an argument you feel needs to be made in a public debate, you should be able to do it without moral apprehension or fear of censorship.

I think the main circumstance where what you are saying, inmywritemind, applies to the public sphere is if someone were to make a public statement purely for the sake of giving offense. But I think such occurrences would be extremely rare, since such an act would have to be motivated by hatred and nothing else. The only examples I can think of would be anonymous statements, for instance on the internet, with the sole purpose of inciting animosity, or acts like vandalism of community centers, publicly placing swastikas/confederate flags, etc. Those are the things I can think of that would fit the description of morally reprehensible because they deliberately give offense.

@Paul, but I do not presume that it’s morally wrong to do something which causes offence *either by accident or deliberately*. I am precisely trying to separate these. Like you, I wouldn’t advocate self-censorship when discussing difficult topics where there is some suspicion someone might be caused to feel offended. I am yet to be convinced of the usefulness of deliberately acting such as to make people attacked/offended, it is *this* aspect that I have been targeting with my comments. It seems odd to suggest that there are no moral stakes to speech, only rhetorical ones. (What about lying, deception by omission, etc…)

@01100110 (!), I basically agree with you.

As Thomas Paine said in the Forester’s Letters: “He who dares not offend cannot be honest.”