‘That Church can have no right to be tolerated by the magistrate which is constituted upon such a bottom that all those who enter into it do thereby ipso facto deliver themselves up to the protection and service of another prince. For by this means the magistrate would give way to the settling of a foreign jurisdiction in his own country, and suffer his own people to be listed, as it were, for soldiers against his own government.’

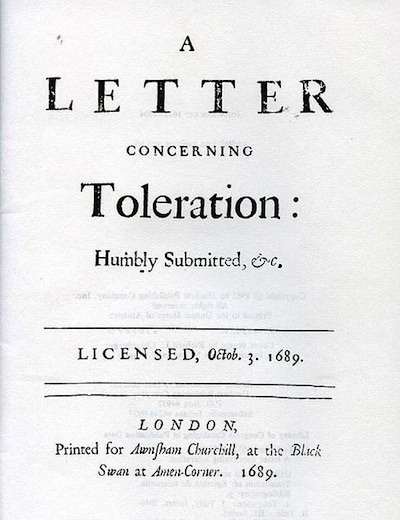

Who wrote that about whom? Not Labour MP Paul Flynn about the new British ambassador to Israel. Nor US Evangelists about Muslims in America. No, it is a quote from John Locke’s 1689 A Letter Concerning Toleration and he is talking about Catholics.

Locke, of course, is generally seen as providing the philosophical foundations of liberalism and the Letter Concerning Toleration is a key text in the development of modern liberal ideas about freedom of expression and worship. Yet, it also reveals how difficult liberals often find it to be liberal.

There is in fact much to admire about A Letter Concerning Toleration. Written at a time when Europe was rent by tempestuous religious strife, and when intolerance and persecution were the norm, it is a powerful argument for religious freedom. Locke’s starting point is the insistence that the duty of every individual is to seek his own salvation. The means to do so are his religious beliefs and the ability openly to worship. The power of human political authority cannot, therefore, rightfully extend over either sphere. The proper concern of civil government is the protection of life, liberty, health and property. The magistrate can use force and violence where this is necessary to preserve civil interests against attack. One’s religious concerns with salvation, however, are not within the domain of civil interests, and so lie outside of the legitimate concern of the magistrate or the civil government.

It is a brave and controversial argument, particularly so given the background of religious bigotry. In the wake of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when the Catholic James II was overthrown by a union of English Parliamentarians and the Dutch Protestant William of Orange, British Catholics were denied the right to vote and sit in Parliament, or to possess army commissions, and no Catholic could ascend to the throne, or even marry a monarch, a prohibition that still remains on the statute books. Against this background of naked bigotry, Locke’s was a refreshing voice.

But Locke’s concept of liberty was also exceeding narrow. ‘Locke’s toleration’, as historian Jonathan Israel observes in Radical Enlightenment, ‘revolves primarily around freedom of worship and theological discussion, placing little emphasis on freedom of thought, speech and persuasion beyond what relates to freedom of conscience.’ It is also grudging ‘in according toleration to some groups and emphatic in denying toleration to others.’

‘No opinions contrary to human society, or to those moral rules which are necessary to the preservation of civil society’, Locke insisted, ‘are to be tolerated by the magistrate’. Catholics ‘ipso facto deliver themselves up to the protection and service of another prince’; their opinions therefore run contrary to ‘the preservation of civil society’ and cannot be tolerated. Locke was even harsher about atheists. Those ‘who deny the being of a God’, Locke insisted, should ‘not at all to be tolerated’. ‘The taking away of God, though but even in thought’, he wrote, ‘dissolves all’.

Today, few charge Catholics with having ‘dual loyalty’, or suggest that the toleration of Catholicism would lead to ‘the settling of a foreign jurisdiction in his own country’. Many, however, continue to make exactly that charge about Jews, and, most especially, about Muslims.

The Florida Family Association, a US evangelical group, has been leading a campaign against All-American Muslim, a reality show that follows the lives of five Lebanese families in Dearborn, Michigan. ‘The show profiles only Muslims that appear to be ordinary folks’, the FFA suggests, ‘while excluding many Islamic believers whose agenda poses a clear and present danger to the liberties and traditional values that the majority of Americans cherish.’ Exactly the same was once said of Catholics. According to the FFA ‘One of the most troubling scenes occurred at the introduction of the program when a Muslim police officer stated “I really am American. No ifs and or buts about it.”’ No Muslim, it seems, can ever be a true American. That, too, was once said about Catholics.

The FFA has pressured advertisers to pull ads from All-American Muslim. It is not surprising that an evangelical group should indulge in such bigotry. What is shameful is that some corporations are willing to give in to such blackmail.

The context of seventeenth century anti-Catholic bigotry is very different from that of contemporary prejudice against Jews and Muslims. But the argument that certain people cannot be real citizens, and that they constitute an insidious threat to the nation, because of their faith or ethnicity, has barely changed. Some arguments never die.

At the time that Locke was writing, there was a very different argument about freedom from Baruch Spinoza. A Dutch Jew who had in 1656 been excommunicated from his local synagogue for his ‘evil opinions’, ‘abominable heresies’ and ‘monstrous deeds’, Spinoza was a leading figure in the Radical Enlightenment, and a champion of individual liberty and free expression.

The starting point for Spinoza was not, as it was for Locke, the salvation of one’s soul but the enhancement of freedom. ‘The less freedom of judgment is granted to men’, he argued in his Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, ‘the further are they removed from the most natural state and consequently the more repressive the regime’. All attempts to curb free expression not only curtails legitimate freedom but is futile. ‘No man… can give up his freedom to judge and think as he pleases, and everyone is by absolute natural right master of his own thoughts’, so ‘it follows that utter failure will attend any attempt in a state to force men to speak only as prescribed by the sovereign despite their different and opposing opinion.’ ‘The right of the sovereign, both in the religious and secular spheres’, Spinoza concludes, ‘should be restricted to men’s actions, with everyone being allowed to think what he wishes and say what he thinks’. It is a view that seems startling even today.

I’ll just play Devil’s Advocate here to encourage a reply, these are not my views.

1) Fine, Locke was a bigot against Catholics, and US evangelicals are bigots against Muslims. But, what about groups such as Jehovah’s Witnesses? This religious group is explicitly anti-State. Would that not be a threat if a real military crisis comes? Sure, Hitler was also a bigot against Jehovah’s Witnesses. But, one may propose not to exterminate or exile the Witnesses, but at least, to keep an eye on them. I think the same goes for plenty of other apocalyptic sects, from Jonestown to Waco. If Gibbon (part of the moderate Enlightenment) was right, the Roman Empire in part fell because of Christian sedition. Perhaps there is a lesson to be learned there.

2) As for Islam, unlike Catholicism, there seems to be doctrinal base to view Muslims with some degree of suspicion in Western secular countries. There is no Muslim pope, of course, and one is never sure what Muslim doctrine may exactly be, but it seems that the notion of Dar Al Harb is well attested in the doctrinal texts. Probably most European Muslims do not think they live in the House of War, but some clerics could convince them, by appealing to religious texts, that they do indeed live in the House of War.

Catholicism in the seventeenth century was also explicitly anti-state, or rather anti- any state whose head didn’t swear fealty to the pope. You can’t project the modern Catholic Church back into 17th century and react as though Locke was talking about sweet old John Paul II. In the 17th century, the pope was a priest-king who was not only a religious prelate, but the ruler of a sizable chunk of territory and commanded his own armies. Further, popes at the time taught that all legitimate secular authority flowed from the papacy, and that it is the solemn duty of faithful Catholics to swear political allegiance to Rome and work to bring their governments under the headship of the pope by whatever means available.

When John Locke was writing, the Elizabethan War, in which Spanish Catholics attempted to conquer England at the behest of the pope in a religious crusade, was still living memory. Guy Fawkes had not too long ago attempted to blow up Parliament as part of a plot to overthrow the English government and bring the island nation under the authority of Rome.

Don’t forget that Pius V had himself attempted to overthrow Elizabeth by sending 600 papal troops to Ireland to assist in the Irish-English War and eventually bring the British Isles under Spanish rule.

The English attitude toward the Catholic Church was hardly “naked religious bigotry.” You’d be suspicious of Catholics, too, if the pope had a habit of giving them money, weapons, and troops to make war on you and bring your country under the rule of his favorite empire.