I gave the Milton K Wong lecture in Vancouver on Sunday. I very much enjoyed the event- it was a stunning venue, a superb audience and a good discussion of the issues. My thanks to the Laurier Institution, University of British Columbia and CBC for inviting me. Entitled ‘What is Wrong with Multiculturalism? A European Perpective’, the lecture pulled together many of the themes about immigration, identity, diversity and multiculturalism of which I have been talking and writing recently. It was a long talk, so I am splitting the transcript into two. Here is the first part; I will publish the second part later this week. It will be broadcast in full on 22 June on the CBC’s Ideas strand.

It is somewhat alarming to be asked to present the European perspective on multiculturalism. There is no such beast. Especially when compared to the Canadian discussion, opinion in Europe is highly polarised. And mine certainly is not the European perspective. My view is that both multiculturalists and their critics are wrong. And only by understanding why both sides are wrong will we be able to work our way through the mire in which we find ourselves.

Thirty years ago multiculturalism was widely seen as the answer to many of Europe’s social problems. Today it is seen, by growing numbers of people, not as the solution to, but as the cause of, Europe’s myriad social ills. That perception has been fuel for the success of far-right parties and populist politicians across Europe from Geert Wilders in Holland to Marine Le Pen in France, from the True Finns to the UK Independence Party. It even provided fuel for the obscene, homicidal rampage last year of Anders Behring Breivik in Oslo and Utøya, which in his eyes were the first shots in a war defending Europe against multiculturalism. The reasons for this transformation in the perception of multiculturalism are complex, and at the heart of what I want to talk about. But before we can discuss what the problem is with multiculturalism, we first have unpack what we mean by multiculturalism.

Part of the problem in discussions about multiculturalism is that the term has, in recent years, come to have two meanings that are all too rarely distinguished. The first is what I call the lived experience of diversity. The second is multiculturalism as a political process, the aim of which is to manage that diversity. The experience of living in a society that is less insular, more vibrant and more cosmopolitan is something to welcome and cherish. It is a case for cultural diversity, mass immigration, open borders and open minds.

As a political process, however, multiculturalism means something very different. It describes a set of policies, the aim of which is to manage and institutionalize diversity by putting people into ethnic and cultural boxes, defining individual needs and rights by virtue of the boxes into which people are put, and using those boxes to shape public policy. It is a case, not for open borders and minds, but for the policing of borders, whether physical, cultural or imaginative.

The conflation of lived experience and political policy has proved highly invidious. On the one hand, it has allowed many on the right – and not just on the right – to blame mass immigration for the failures of social policy and to turn minorities into the problem. On the other hand, it has forced many traditional liberals and radicals to abandon classical notions of liberty, such as an attachment to free speech, in the name of defending diversity. That is why it is critical to separate these two notions of multiculturalism, to defend diversity as lived experience – and all that goes with it, such as mass immigration and cultural openness – but to oppose multiculturalism as a political process.

To make my case I want to begin by questioning three myths of immigration. Three myths at the heart of the discussion about multiculturalism. Three myths created by the confusion I have just described. Three myths that have also helped maintain that confusion. The first is the idea that European nations used to be homogenous but have become plural in a historically unique fashion. The second claim is that contemporary immigration is different to previous waves, so much so that social structures need fundamental reorganization to accommodate it. And third is the belief that European nations have adopted multicultural policies because minorities demanded it. Both sides in the multiculturalism debate accept these claims. Where they differ is in whether they view immigration, and the social changes it has brought about, as a good or as an ill. Both sides, I want to suggest, are wrong, because these three premises upon which they base their arguments are flawed.

* * * * *

The claim that European nations used to be homogenous but have been made diverse by mass immigration might appear to be common sense. In fact, most European nations are in fact less plural now than they were, say, a hundred years ago. The reason we imagine otherwise is because of historical amnesia and because we have come to adopt a highly selective standard for defining what it is to be plural.

Consider France. At the time of the French Revolution, less than half the population of France spoke French. The historian Eugene Weber has shown how traumatic and lengthy was the process of what he calls ‘self-colonisation’ required to unify France and her various populations. These developments created the modern French nation. But they also reinforced in the elite a sense of how alien was the mass of the population. Here is the Christian socialist Phillipe Buchez addressing the Medico-Psychological Society of Paris in 1857:

Consider a population like ours, placed in the most favourable circumstances; possessed of a powerful civilisation; amongst the highest ranking nations in science, the arts and industry. Our task now, I maintain, is to find out how it can happen that within a population such as ours, races may form – not merely one but several races – so miserable, inferior and bastardised that they may be classed below the most inferior savage races, for their inferiority is sometimes beyond cure.

One only has to read the novels of Émile Zola or the works of Count Arthur Gobineau, one of the leading racial scientists of his day, to recognize how widespread was this sentiment.

The social and intellectual elite in France, far from viewing their nation as homogenous, regarded most of their fellow Frenchmen not as ‘one of us’, but as racial alien, and so inferior that they stood below the ‘most inferior savage races’ and were ‘beyond cure’.

In Victorian England, too, the elite viewed the working class and the rural poor as the racial Other. A vignette of working class life in the Saturday Review, a well-read liberal magazine of the era, is typical of English middle class attitudes:

The Bethnal Green poor… are a caste apart, a race of whom we know nothing, whose lives are of a quite different complexion from ours, persons with whom we have no point of contact… Slaves are separated from whites by more glaring marks of distinction; but still distinctions and separations, like those of English classes which always endure, which last from the cradle to the grave, which prevent anything like association or companionship, produce a general effect on the life of the extreme poor, and subject them to isolation, which offer a very fair parallel to the separation of the slaves from the whites.

Modern Bethnal Green is not home to warehousemen or costermongers, but lies at the heart of the Bangladeshi community in East London. Today’s ‘Bethnal Green poor’ are often seen as culturally and racially distinct. But only those on the fringes of politics would compare the distinctiveness of Bangladeshis to that of slaves. The sense of apartness was far greater in Victorian England than it is contemporary Britain. And that’s because in reality the social and cultural differences between a Victorian gentleman or factory owner, on the one hand, and a farmhand or a machinist, on the other, weremuch greater than those between a white resident and one of Bangladeshi origin living in Bethnal Green today.

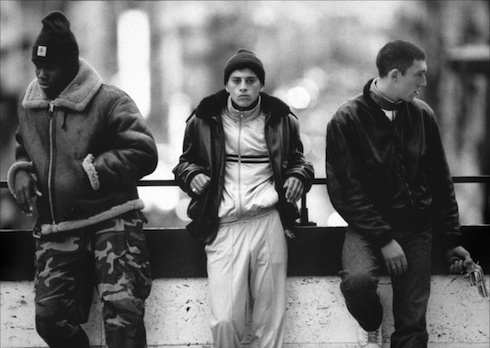

However much they may view each other as different, a 16-year-old kid of Bangladeshi origin living in Bethnal Green, or a 16-year-old of Algerian origin living in Marseilles, or a 16-year-old of Turkish origin living in Berlin, probably wears the same clothes, listens to the same music, watches the same TV shows, follows the same football club as a 16-year-old white kid in that same city. The shopping mall and the sports field, the TV and the iPod, have all served to bind differences and create a set of experiences and cultural practices that is more common than at any time in the past.

There is nothing new, then, in plural societies. From a historical perspective contemporary societies, even those transformed by mass immigration, are not particularly plural. What is different today is the perception that we are living in particularly plural societies, and the perception of such pluralism in largely cultural terms. The debate about multiculturalism is a debate in which certain differences (culture, ethnicity, faith) have cometo be regarded as important and others (such as class, say, or generational), which used to be perceived as important in the past, have come to be seen as less relevant. Why this has happened I will come to later.

* * * * *

The second myth I want to challenge is the claim that contemporary immigration to Europe is different, and in some eyes less assimilable, than previous waves. In his much-lauded book Reflections on a Revolution in Europe the American writer Christopher Caldwell suggests that prior to the Second World War, immigrants came almost exclusively from other European nations, and so were easily assimilable. ‘Using the word immigration to describe intra-European movements’, Caldwell suggests, ‘makes only slightly more sense than describing a New Yorker as an “immigrant” to California’. According to Caldwell, prewar immigration between European nations was different from postwar immigration from outside Europe because, ‘immigration from neighboring countries does not provoke the most worrisome immigration questions, such as “How well will they fit in?” “Is assimilation what they want?” and, most of all, “Where are their true loyalties?”.’

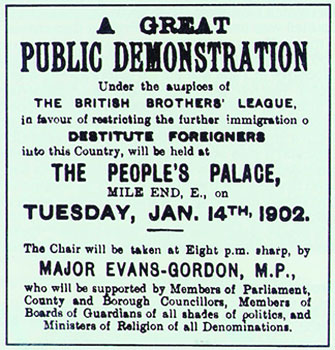

In fact, those were the very questions asked of European migrants in the prewar years. In 1903, the British Royal Commission on Alien Immigration expressed fears that newcomers were inclined to live ‘according to their traditions, usages and customs’ and there were fears that there might be ‘grafted onto the English stock… the debilitated sickly and vicious products of Europe’.

Britain’s first immigration law, the 1905 Aliens Act, was designed primarily to bar European Jews, who were seen as unBritish. The Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour, observed that without such a law, ‘though the Briton of the future may have the same laws, the same institutions and constitution… nationality would not be the same and would not be the nationality we would desire to be our heirs through the ages yet to come.’

In France, nearly a third of the population in the 1930s were immigrants, mostly from Southern Europe. Today we think of Italian or Portuguese migrants as culturally similar to their French hosts. Seventy years ago they were viewed as aliens, given to crime and violence, and unlikely to assimilate into French society. ‘The notion of the easy assimilation of past European immigrants’, the French historian Max Silverman has written, ‘is a myth’.

One of the consequences of postwar migration has been to create historical amnesia about prewar attitudes, just as it has created historical amnesia about the divided nature of European societies before such immigration. From a historical perspective, there is little that is unique about contemporary migrants, or in the way that host societies perceive them.

* * * * *

The third myth that underlies much of the discussion of European multiculturalism is that European nations have become multicultural because minorities wished to assert their differences. The question of the cultural difference of immigrants has certainly preoccupied the political elites. It is not a question, however, that, until recently, has particularly engaged immigrants themselves.

Take Britain. The arrival in the late 1940s and the 1950s of large numbers of immigrants from India, Pakistan and the Caribbean, led to considerable unease about its impact upon traditional concepts of Britishness. As a Colonial Office report of 1955 observed, ‘a large coloured community as a noticeable feature of our social life would weaken… the concept of England or Britain to which people of British stock throughout the Commonwealth are attached’.

The migrants certainly brought with them a host of traditions and habits and cultural mores from their homelands, of which they were often very proud. But they were rarely concerned with preserving cultural differences, nor thought of it as a political issue. What inspired them was the struggle not for cultural identity but for political equality. And they recognized that at the heart of that struggle was the creation of a commonality of values, hopes and aspirations between migrants and indigenous Britons, not an articulation of unbridgeable differences.

This is equally true of the group whose traditions, beliefs and mores are widely perceived to be most distinct from those of Western societies, and hence the group that is supposedly most demanding that its differences be publicly recognized: Muslims.

The patterns of Muslim migration have, in fact, been little different to that of other communities. The best way to understand it, as of much postwar migration to Europe, is in terms of three generations: the first generation that came to Europe in the 50s and 60s; the second generation that were born or grew up in the 70s and 80; and the third generation that has come of age since then. This is, I know, a somewhat crude characterisation, but it is also a useful to have a broad-brush understanding of the changing relationships between migrants and European societies. The illustrations I am giving come primarily from Britain. But the structure applies to immigration to other European countries too.

The first generation of Muslim immigrants to Britain, who came almost entirely from the Indian subcontinent, were pious in their faith, but wore it lightly. The British writer and theatre director Pervaiz Khan, whose family came to Britain in the 1950s, remembers his father and uncles going to the pub for a pint. ‘They did not bring drink home’, he says. ‘And they did not make a song and dance about it. But everyone knew they drank. And they were never ostracised for it.’ No woman wore a hijab, let alone a niqab or burqa. His family ‘rarely fasted at Ramadan’, Khan says, ‘and often missed Friday prayers. They did not boast about it. But they were not pariahs for it. It is very different from today.’

Khan’s experience was not unusual. My parents were very similar. And those of most of my friends. Their faith expressed for them a relationship with God, not a sacrosanct public identity. Islam was not, in their eyes, an all-encompassing philosophy.

The second generation – my generation – was primarily secular. I am of a generation that did not think of itself as ‘Muslim’ or ‘Hindu’ or ‘Sikh’, or even often as ‘Asian’, but rather as ‘black’. Black was for us not an ethnic label but a political badge. The ‘Muslim community’, in the sense of a community that defined itself solely, or even primarily, by faith did not exist when I was growing up. Neither did the Sikh community, or the Hindu community.

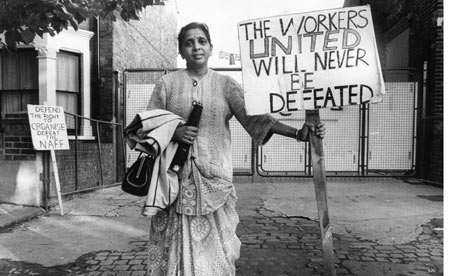

Unlike our parents’ generation, who had largely put up with discrimination, we were fierce in our opposition to racism. But we were equally fierce in our opposition to religion and to the traditions that often marked immigrant communities. Religious organizations were, in my youth, barely visible. The organizations that drove migrant communities were primarily secular, often socialist: the Asian Youth Movements, for instance, or the Indian Workers Association.

It is only with the generation that has come of age since the late 1980s, that the question of cultural differences has come to be seen as important. A generation that, ironically, is far more integrated than the first generation, is also the generation that is most insistent on maintaining its ‘difference’. That in itself should make us question the received wisdom about how and why multicultural policies emerged.

The shift in the meaning of a single word expresses the transformation I am talking about. When I was growing up to be ‘radical’ was to be militantly secular, self-consciously Western and avowedly left-wing. To be someone like me. Today ‘radical’ in a Muslim context means the very opposite. It describes a religious fundamentalist, someone who is anti-Western, who is opposed to secularism.

What I have said of Britain is true also of other European countries, Germany, for instance, or France. The irony in France is that, for all the current hostility of the French state to Islam, and to public displays of Islamic identity, such as the burqa, for most of the postwar years, while migrant workers were defiantly secular, successive governments regarded such secularism as a threat and attempted to foist religion upon them, encouraging them to maintain their traditional cultural identities. Paul Dijoud, minister for immigrant workers in the 1970s government of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, declared that ‘The right to a culture identity allows the immigrant, despite his geographical distance, to stay close to his country.’ The government sought in Islam ‘a stabilizing force which would turn the faithful from deviance, delinquency or membership of unions or revolutionary parties’. When a series of strikes hit car factories in the late seventies, the government encouraged employers to build prayer rooms in an effort to wean immigrant workers, who formed a large proportion of the workforce, away from militant activity.

The claim that minority communities have demanded that their cultural differences be publicly recognized and affirmed is, then, historically false. That demand has emerged only recently. The myth that multiculturalism was a response to minority demands gets cause and effect the wrong way round. Minority communities did not force politicians to introduce multicultural policies. Rather, as I shall show later, the desire to celebrate one’s culture identity has itself, in part at least, been shaped by the implementation of multicultural policies.

* * * * *

The three myths I have talked about are important because they underlie so much of the discussion of immigration and multiculturalism in Europe, and shape both sides of the debate. Having hopefully laid them to rest, I want now to rethink both multiculturalism and the criticism of it. And to begin to do that by looking at how multicultural policies historically have developed.

This is, however, not a single story. Throughout Europe, multicultural policies have developed in response to mass immigration. But they have done so in different ways. Britain and Norway, Sweden and Germany, Holland and Denmark – every country has its own specific multicultural history to tell. What I want to do, therefore, is to look at two contrasting histories – that of Britain and Germany – to understand what these histories have in common despite their differences.

Let us begin in Britain. While the question of cultural differences preoccupied the political elite in the 1950s and 1960s, it was not one, as I have already suggested, that particularly troubled immigrants themselves. What preoccupied them was not the desire to be treated differently, but the fact that they were treated differently. Racism and inequality, not religion and ethnicity, were, for them, the key issues.

Throughout the Sixties and Seventies, four big issues dominated the struggle for political equality: opposition to discriminatory immigration controls; the struggle against workplace discrimination; the fight against racist attacks; and, most explosively, the issue of police brutality.

These struggles politicised a new generation of black and Asian activists and came to an explosive climax in the riots that tore through Britain’s inner cities in the late Seventies and early Eighties. The authorities recognized that unless black communities were given a political stake in the system, their frustration could threaten the very stability of British cities. It was against this background that the policies of multiculturalism emerged.

Local authorities in inner city areas pioneered a new strategy of making black and Asian communities feel part of British society by organising consultations, drawing up equal opportunity policies, establishing race relations units and dispensing millions of pounds in grants to minority organisations. At the heartof the strategy was a redefinition of racism. Racism now meant not simply the denial of equal rights but the denial of the right to be different. The old idea of British values or a British identity was defunct. Rather than be expected to accept British values, or to adopt a British identity, different peoples should have the right to express their own identities, explore their own histories, formulate their own values, pursue their own lifestyles.

Scepticism about the idea of a common national identity arose in part from cynicism about the idea of ‘Britishness’. There was widespread recognition among blacks and Asians that talk about Britishness was a means not of extending citizenship to all Britons, whatever their colour and creed, but of denying equal rights to certain groups. But the new strategy did not simply challenge old-fashioned ideas of Britishness. It transformed the very meaning of equality. Equality now meant not possessing the same rights as everyone else, despite differences of race, ethnicity, culture or faith, but possessing different rights, because of them.

In 2000, the Commission on the Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain, chaired by the philosopher Bhikhu Parekh, published its report that famously concluded that Britain was a ‘community of comunities’ in which equality ‘must be defined in a culturally sensitive way and applied in a discriminating but not discriminatory manner’. The Parekh report has come to be seen as defining the essence of multiculturalism. But the arguments at its heart had emerged out of the response, two decades earlier, to the inner city riots. The consequences of these arguments I will come to later. But first I want to turn to the question of multiculturalism in Germany.

* * * * *

Germany’s road to multiculturalism was different to Britain’s, though the starting point was the same. Like many West European nations, Germany faced an immense labour shortage in the postwar years and actively recruited foreign workers. Unlike in Britain, the new workers came not from former colonies, but initially from Italy, Spain and Greece, and then from Turkey. And these workers came not as immigrants, still less as potential citizens, but as ‘guest workers’, who were expected to return to their country of origin when no longer required to service the German economy.

Over time, however, immigrants became transformed from a temporary necessity to a permanent presence. This was partly because Germany continued relying on their labour, and partly because immigrants, and more so their children, came to see Germany as home. But the German state continued to view them as outsiders and to refuse them citizenship. There are nearly 4 million people of Turkish origin in Germany today. Barely half a million have managed to become citizens. Nor is it just first generation immigrants who are denied citizenship; their German-born children are excluded too.

Instead of creating an open society, into which immigrants were welcome as equals, German politicians from the 1980s onwards dealt with the so-called ‘Turkish problem’ through a policy of multiculturalism. In place of citizenship and a genuine status in society, immigrants were ‘allowed’ to keep their own culture, language and lifestyles. The consequence was the creation of parallel communities. The policy did not so much represent respect for diversity as provide a means of avoiding the issue of how to create a common, inclusive culture.

First generation immigrants were often secular, and those that were religious wore their faith lightly. Today, almost a third of adult Turks in Germany regularly attend mosque, a far higher rate than among Turkish communities elsewhere in Western Europe, and higher than in most parts of Turkey. First generation women almost never wore headscarves. Many of their daughters do. Without any incentive to participate in the national community, many did not bother learning German.

At the same time as Germany’s multicultural policies encouraged immigrants to be at best indifferent to mainstream German society, at worst openly hostile to it, they also made Germans increasingly antagonistic towards Turks. The sense of what it meant to be German was in part defined against the values and beliefs of the excluded migrant communities. And having been excluded, it has become easier to scapegoat immigrants for Germany’s social ills. A recent poll showed that more than a third of Germans think that the country is ‘over-run by foreigners’ and more than half felt that Arabs were ‘unpleasant’.

In Germany, the formal denial of citizenship to immigrants led to the policy of multiculturalism. In Britain, the promotion of multicultural policies led to the de facto treatment of individuals from minority communities not as citizens but simply as members of particular ethnic groups. The consequence in both cases has been the creation of fragmented societies, the alienation of many minority groups and the scapegoating of immigrants.

Part 2 of this transcript is here.

The pictures are, from the top down, the Toronto Monument to Multiculturalism; Eugène Delacroix’s 1830 painting La Liberté guidant le people; a still from the film La Haine; a poster for an anti-immgration demonstration in 1902; Jayaben Desai, leader of the Grunwick strike in 1976; a poster for a demonstration about the Bradford 12 trial; a police van burning in the 1981 Brixton riots; and Turkish immigrants outside Munich train station, 1973.

This is a very interesting idea. As far as I understand it, what you are saying is that what passes for multiculturalism and diversity in modern society is really fragmentation masquerading as a diverse whole? You are probably already familiar with this, but just in case –

Thank you so much for your presentation at The Chan Centre. Your presentation helped me to find the words I often need when faced with irrational comments regarding race and immigration.Your comments on Canada’s “guest workers” will hopefully reach the very closed ears of our federal government. Mistreatment of our guest workers is a hidden horror in Canada. I hope to be able to continue to listen to you on BBC.

Jacqui……how so. Where do you see a horror? I am the son an immigrant, with roots that go back to Canadas original settlers mixed with First Nations. I rub elbows and work alongside Filipinos, Arabs, Africans, Asians and Europeans daily. They have their problems no less than my father had his coming here. These individuals bring a huge enrichment to the community at large, no less or more than any other immigrants ever.

To carte blanche call this a horror makes light of the real life situations that they face in trying to assimilate. For the most part I see and experience happy people and most of them are usually a joy to be around.

Further I think, what your asking for is more politicization, which if im right, then I think you miss the greater point of what i feel the author was trying to impart and you fell into I beleive the third part of his essay in which the government imposed multiculturalism as opposed to a very simple and honest “here are the rules, here are the customs as we have them today, how can we help, this is what we are able to offer, here is how you can contibute” and everyone regardless of gender or race is equal.

Little else is required. Instead of isolation, which is what our multicultural universality has done, open the doors to true equality.

The multicultural Canada I have come to see as originally envisioned is one that has led to polarization across all communities, ethnicity, cultural beliefs and heritages. I feel we have allowed an error and are compounding this mistake in our out look and how we deal with the realities of being living working and growing Canada.

I find what the author is saying to be true and makes sense.

As opposed to the doors becoming more open I find(myself included) we are becoming more closed. Hence real problems not only today but in the future.

The only politics we need are ones that dismantle old stereotypes and make Canada inclusive for all who are and become part of Canada.

I am talking about the people who come here to work but not as immigrants. The farm workers here in BC for instance and many of the construction workers who are brought in as “guest workers”. Research with the unions and organizations that work with these people will show you what is wrong and how marginalized and lied to many of them are. Ask the BC Federation of Labour-they can give you lots of info.

Well Jacqui, just to reiterate a little, horror is what is happening to innocents in Syria or in the Sudan. What you call horror here in Canada is a cheap play on words to drown out any dissenting thought or idea.

There will always be individuals who lie and cheat to take advantage of others. Everywhere in the world. To change that paradigm here justice must be swift and harsh. Neither of which exists in Canada.

No matter how or what we legislate this will always be. Where do you propose we add more legislation. From a Canadian perspective we can already see what a multicultural, plural society looks like, how it acts and how destructive it is to the overall fabric of our country. This, without looking to the experiments in multicultural societies in Europe.

I work with and around a lot of those “guest workers”. A lot of those “guest workers” are also trying to become more than “guest workers”. Hope you don’t mind if I call them people and some my friends. Most would like nothing better than to achieve landed immigrant status.

The first problem with your premise is that the unions are there for the welfare of these workers, they are not. The unions are there for the unions, nothing else. The volume of these propaganda machines is turned up high saying “look how as a society we are not looking after this. So if they were part of our union we could fix this”………okay.

What you bring up with people taking advantage of “guest workers” is excellent example of how the climate of multiculturalism works against all of us.

Instead of working in a climate of no fear they get stuck in enclaves of people with maybe similar back grounds and or cultures, where more often than not, false fears of repercussions or non inclusion echo.

This is where they get played upon. Instead of reaching out, they reach in, closing doors to the aide they need. Most of that aide comes in the form of being able to interact freely within the society they are contributing to, enriching it making it stronger. This is how they contribute.

The resources they have and need become self limiting as opposed to self enriching. Which means we all get robbed.

Re: Mr. Maliks parents, that generation.

As I mentioned earlier the solution I think is “here are the rules, here are the customs as we have them today, how can we help, this is what we are able to offer, here is how you can contribute” and everyone regardless of gender or race is equal. It makes no difference if you are a guest worker or an applicant for immigration. You are either included or not. IF you are not you aren’t here.

If I got it well, the policies of multiculturalism are wrong, because they are nothing more then essentialised mini-nationalisms not related to territory in immigration cases, but to the essentialization of cultural traits of a social group, and related to territory in the case of ethnic minorities in the Balkans. Yet I am worried, because in the Balkan case, this kind of failure of multiculturalism is leading towards a kind of nationalist revanshism, by the new hidden nationalist intellectual elites (people who have been studying in western universities telling to us down here that even western universities are saying that multi-kulti failed and is time for new grand narratives)…. Even people from the left are using Zizek’s critique of decafeinized cafe (meaning for the so-called liberal multiculturalism) to back their opinion against multiculturalist legal frames that guarantee minority rights….

So I think that this is a good critique, separating the ideal of multiculturalism from wrong practices with the same name. But I wish that you could be able to deal with local perceptions, and consequences, of your critique.

Thank you from Albania

Excellent talk yesterday. Your analysis is spot on. My only issue with the event was that you were introduced as an antagonist of sorts. That was unfortunate, because the message you presented would only be perceived as antagonistic by those who are dogmatic about their beliefs, and such dogma has no place in an academic debate.

I realize my question yesterday was poorly phrased, in large part thanks to my sometimes failing English. Allow me therefore to ask the question again, in a clearer way (there are two actually, but who’s counting):

Based on your analysis one could argue that the emergence of multiculturalism as a political term was fuelled by what is commonly referred to as ‘white guilt’ or ‘liberal guilt’ – in an effort to right the wrongs of the past and show that we are now more inclusive than those before us we created an atmosphere in which we, as they say in Norway, “sew pillows under the arms of” those of other ethnicities. If my understanding is right, I agree with you, but this is a complicated revelation:

Multiculturalism seen through this prism makes historical and societal sense. If it is true that this approach unintentionally lead to stronger demarcation lines between ethnic groups and the ‘radicalization’ of younger generations, a large mistake was made and that mistake has to be corrected. But how do we do that? Your suggestion, and the answer you gave to my question (which I believe is accurate) is that we need to start focusing on our similarities and work together to form our society rather than focus on our differences and work to emphasize them.

That leads to the next part of my question: The problem with this approach is that in many cases those that move to a new country (myself included) insist on keeping their own traditions and beliefs alive in spite of the norms and traditions of that new country. For me, a white male from Western Europe now living in Canada, this is not very hard to do because on the face of it my traditions and beliefs may appear to match those of my adopted country. But when this attitude is promoted by people from dramatically different cultures, whether it be South East Asia, Africa, Arabia or even South America, it causes a dissonance in the established population. The general attitude of the “natives” (I use that term loosely) seems to be that if you move to a new country, you should adopt the laws, norms, ideals and traditions of that country. Let’s call this ‘assimilation’ or ‘indoctrination’. This is a hard line and it is promoted by people who feel the need to protect their ‘way of life’ and their traditions.

What I believe is a better path for everyone, and what I think you are promoting, is a path of ‘inclusion’ and ‘adaptation’ in which the “newcomers” are welcomed and allowed to keep their traditions (as long as they are not contrary to the laws of the land) if they like or adopt those of their new country if they like. This is a soft line and one that in theory at least should lead to a more harmonious diverse nation.

The problem with this approach can be seen quite clearly here in Greater Vancouver, and it was addressed earlier in the week on a town hall meeting broadcast on CBC Radio: The ‘inclusion’ approach combined with hard line immigrants leads to enclaves. As a result you have sections of the city where the population is almost exclusively of one ethnicity. In extreme cases it can go so far that you can’t function normally unless you speak and understand the language of this ethnicity and those that live in these sections demand to be treated differently. That, in my opinion, is problematic. Not because there is anything wrong with that ethnicity or their ideals, but because they deliberately remove themselves from society as a whole and cocoon themselves.

I believe it is this last scenario, combined with blatant racism and bigotry, that fuels people like Breivik and his ilk: An irrational fear that ‘the other’ comes to the ‘motherland’ to insert their own ideals on the culture with the goal of supplanting it altogether. Of course this is utter nonsense bordering on insanity, but it is easy to see how an underinformed person might believe it to be true.

So how do we deal with this? How do we fix our approach to modern diverse society without in the process producing either the need for ethnic demarcation or encouraging ethnic enclaves? Our goal should be true multiculturalism and diversity as in your original culture is of less relevance than where you currently live. But getting to that point seems an almost insurmountable challenge.

To put it plainly: If your analysis is correct, where do we go from here?

First, my apologies for taking so long to respond. I have been away and I’m only just catching up on comments and responding to them.

Many thanks for your questions, both here and in Vancouver. We should not confuse two things. The first is the idea that there may be a set of values, institutions, forms of governance, etc, under which all people best flourish. The other is the insistence that immigrants ‘should adopt the laws, norms, ideals and traditions of the country’ to which they have migrated. No country possesses a single set of ‘norms, ideals and traditions’. This is the myth of homogeneity against which I was arguing. All societies embody conflicts over appropriate norms, ideals and traditions. Your vision of what constitutes Norwegian norms is very different from that of Anders Behring Breivik. Marine Le Pen’s concept of what constitutes the French tradition is different from Francoise Hollande’s. And his would be different from mine, were I a French citizen. Indeed, it is different from mine as a British citizen. The idea that immigrants must assimilate to the host country’s ‘norms or ideals or traditions’ avoids the inconvenient fact that these are all, or should be, contested claims.

The myth of homogeneity is the other side of the coin to multiculturalism. Both multiculturalists and many of their critics seek to minimize social conflicts by policing culture. But in so doing, they only unleash more intractable conflicts by reposing political problems in terms of culture, ethnicity or faith.

I am not arguing for some kind of conflict-free, inclusive Utopia. Only dead societies lack conflict. It is out of the clashes and conflicts that diversity brings that cultural and political engagement emerges. Diversity, as I put it in the second part of my talk, is important, not in and of itself, but because it allows us to break out of our culture-bound boxes, by engaging in dialogue and debate and by putting different values, beliefs and lifestyles to the test. The kind of conflict about which I am talking is, ironically, the only means through which to create a more universal language of citizenship, or establish a common set of values or institutions.

So, where, you ask, do we go from here? Well, we begin by dropping the crass pretence of cultural homogeneity and the yearning for ‘social cohesion’. We see instead the messiness of diversity as the raw material of conflict and therefore of engagement.

There is nothing inherently wrong with people ‘keeping their own traditions and beliefs alive’ so long as they don’t seek to politicize this process, or to pretend that traditions and beliefs are fixed and inviolable. The problem isn’t that societies have a diversity of traditions or beliefs. It is the attempt to seek political refuge in the fixity of such traditions or beliefs. That’s the problem of identity politics, whether of the right or the left.

Political conflicts are often useful because they repose social problems in a way that asks: ‘How can we change society to overcome that problem?’ We might disagree on the answer, but the debate itself is a useful one. Another way of putting this is that political conflicts are the kinds of conflicts necessary for social transformation. Multiculturalism, on the other hand, by reposing political problems in terms of culture or faith, transforms political conflicts into a form that makes them neither useful nor resolvable. Rather than ask, say, ‘What are the social roots of racism and what structural changes are required to combat it?’, it demands recognition for one’s particular identity, public affirmation of one’s cultural difference and respect and tolerance for one’s cultural and faith beliefs. Even before we start talking of policy, it is this idea, and this process, that needs to be challenged.

Reblogged this on holes/and/spaces and commented:

This is such a relevant post to what I’m re-experiencing, moving back into a city. Not just any city, but THE city. Driving through the boroughs of New York is like crossing invisible borders. Going from one street to the next, it’s no surprise to see a sudden shift in ethnic composition. For example, we were driving in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, driving eastwards. You would see Latinos, Blacks then suddenly Orthodox Jewish men dressed in traditional black clothes. It’s something that I’ve been used to for most of my life. Even beyond cities, in different countries, and even countries in such close proximity like Canada and the US, the difference in the reception of diversity and multiculturalism is quite vast. This has a lot to do with the different policies of each nation implements. The institutionalization of diversity which trails behind the “lived experience” which aims to accommodate the cultural and economic differences. The most interest region to look out for is Europe, which has recently experienced a manifestation of what Americans call “terrorism.” With a decreasing birth rate hanging below the replacement rate, the cluster of socialist countries will not be able to sustain the old age pensions with its aging population.

There are many myths, especially the ones in this post, which fuels more hatred towards the minorities. This hatred is more pronounced during economic downturns such as the one we’re experiencing, as more people are unemployed and disgruntled. In this situation, minorities and new immigrants are easy scapegoats to blame. There is hope, however, seeing that there have been surprisingly a historical trend toward more openness (i.e. France since the revolution vs. the film, Haîne), anthropologically speaking.

I agree with everything here. As usual, I’ll just play Devil’s Advocate (in part, because I frequently hear these arguments, and I’d like to know how you’d reply). You are basically advocating an assimilationist policy, French Republican style; or a melting pot, American style. Multiculturalists will argue that, on paper, that looks great, but not in practice. In fact, that was Fanon’s dissatisfaction in France: he was told that the French Empire was colorblind, but once he went to continental France, realized that it wasn’t so. Now, inasmuch as the prevalent culture is not prepared to accept individuals that come from minorities (in virtue of their skin color, or accent, or religious preferences, no matter how mild they might be), they argue that their best line of defense is to adhere to old identities. Inasmuch as they are not accepted as westerners no matter how hard they try to assimilate, they are better off fully embracing their ethnic identity; as that will protect them much better against abuses and discrimination.

Just as there are two notions of multiculturalism that are constantly confused, so there two notions of assimilation that are rarely distinguished. On the one hand, assimilationism has come to mean the resolve to treat everyone as citizens, not as bearers of specific racial or cultural histories. On the other it has come to mean an insistence that equality requires a high degree of cultural homogeneity, and hence requires immigrants to give up their differences in the name of social cohesion and national unity. Assimilationism is this sense is a means not of enforcing equality but of pointing up differences, and of tolerating, indeed of institutionalising racism. So, yes, those who criticize the French model are absolutely right. But that, of course, is not an argument for multiculturalism. If I were to construct an ideal immigration/citizenship policy, it would be to marry multiculturalism, in the sense of enhancing the lived experience of diversity, with assimilationism, in the sense of the resolve to treat everyone as citizens, rather than as bearers of specific racial or cultural histories. In practice what European nations have done is the very opposite. Different countries have institutionalised either multiculturalism, in the sense of policies to place minorities in boxes, or assimilationism, in the sense of equality as meaning the giving up of cultural or religious differences. Both, in other words, have rejected the best aspects of their outlook, and institutionalized the most wretched parts.

Nothing much to add, though it would be interesting to get together in a pub (one thought though: you should take a look at Elias Canetti’s ‘Die Gerettete Zunge’ – don’t know what it is called in English – for a really magical description of quite how ‘multicultural’ central europe could be a hundred years ago, and Mark Mazower’s Dark Continent for an investigation of what went wrong).

Other than that, was Caldwell’s book really widely lauded? The only reviews that I read mauled it.

Ideology often fulfils role of state religion

Religion has played a significant role in the affairs of the state for a long time. States have been formed on the basis of religion; wars have been fought in the name of religion, and kings have helped establish and propagate a new religion from time to time… Modern times are no exception to this phenomenon. There are still states that are ruled by theocrats. There are states that although they are not strictly theocracies, have state religions. Canada does not have a state religion in the strict sense of the word. It is not a theocracy either. In a theocracy, the political and administrative powers are in the hands of the priests or religious leaders. Laws of the land are interpreted by the ecclesiastical authorities as, for example, in modern-day Iran.

SOME OTHER STATES, though not ruled by priests are, as a matter of fact, religious states. A single religion is prescribed as the state religion. The laws of the land are not interpreted by religious authorities, but have a basis in the tenets of a single religion. Many countries of the Middle East fall into this category. In such countries, Islam enjoys the most-favored-religion status. In countries like Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, Islam is the state religion. These and other theocratic countries, like Nepal, limit the proselytizing by adherents of other faiths. Religion plays a different kind of role in countries like the.. U.S.S.R. There the traditional religion has been replaced by official atheism. The place previously occupied by the church has been replaced by salutation to the Revolution. The tombs of the leaders of the Revolution become national shrines in such states.

MANY COUNTRIES of Eastern Europe (until recently), and some countries of Asia, Africa and Central America are ruled by a single political party. Communism, or a variation of it, is the state philosophy. It permeates throughout the social, political, economic and education systems of countries like Cuba, the U.S.S.R. and Vietnam. Opposition to the state philosophy is strictly curtailed. Dissidents are often jailed or exiled if not executed. In another set of countries, religion plays a role in different ways. These countries do not have a state religion in the strict sense of the word, but the state has established a particular state philosophy for promoting social and political developments within its boundaries. When a state promotes a single set of national values, that state is considered by authorities as practising a civil religion…

THERE ARE MANY countries that have established a single-state * ideology. That ideology then becomes that state’s civil religion. This is explained well by authors like R. Richey and D. Jones in American Civil Religion. Robert Bellah, a noted political scientist, explained in an article published in Society that a “religious feeling toward the American state arises because the government takes no stance on religion.” Professors William Cole and Phillip Hammond writing in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion hypothesize that “civil religion originates because: 1) the condition of religious pluralism creates special problems for social interaction; 2) social interactions in such situations is facilitated by a universalistic legal system; and 3) a universalistic legal system may, therefore, be elevated to a sacred realm.” Professor Hammond has also quantified various publications on civil religion in his essay, The Sociology o!

f American Civil Religion, published by Sociological Analysis. In fact, there is considerable discussion of civil religion in American publications. The Canadians, as usual, have still to follow the lead.

DEFINITIONS OF THE term “civil religion” have been given by many.. scholars. Professor Thomas M. McFadden of St. Joseph College, Philadelphia, defines civil religion as “the acceptance and, to varying degrees, the institutionalization of a set of values, symbols and rituals . . . which serves as the cohesive force and centre of meaning for a nation.” Another authority, Robert Nisbet, describes civil religion as “the religious or quasi-religious regard for certain civic values and traditions. . . Such regard may be marked by special festivals, rituals, creeds and dogmas . . .” Western as well as Eastern nations have been followers of civil religion for some time now. This term “civil religion” was first used by Jean-Jacques!

Rousseau in his book The Social Contract. He believed that Christianity could not satisfy the religious needs of a modern state like France. Instead he proposed the possibility of a civil religion “of which the sovereign would fix the articles.” These articles were then to become a cornerstone of good citizenship. All faithful subjects were to believe in those articles of faith. ANOTHER AUTHOR, Fustel de Coulanges, described the civil religions.. of ancient Greek and Roman city states in his book, The Ancient City (1864). One of the best examples of a non-western, non-Communist nation promoting a single-state ideology is Indonesia. The civil religion of Indonesia is known as Panchashila. It was proclaimed by President Suharto as the state ideology just as former prime minister Pierre Trudeau proclaimed the state ideology of multiculturalism in Canada some 20 years ago. Panchashila is a derivative of the Sanskrit word which means five pillars. (These five pillars are not to be confused with the Panchashila of the non-aligned nations.)

The five principles or silas of Indonesia are: 1) The principle of one lordship or belief in one supreme being; 2) humanitarianism (just as civilized humanity) or a commitment to internationalism; 3) nationhood/nationalism (unity of Indonesia); 4) peoplehood (wisdom in deliberation/representation); and 5) social justice.

THESE PRINCIPLES are virtually a national ideology and civil religion of Indonesia. They are taught in schools, proclaimed in.. government documents and distributed across the many thousand of islands of Indonesia just as Canada and her provinces promote their brands of multiculturalism. Readers may see some similarities in these Indonesian principles and those principles proposed by the successive Canadian governments. But, of course, differences are also quite apparent.

The Canadian Multicultural Act, July 1988, states, “It is hereby declared to be the policy of the government of Canada to: a) recognize and promote the understanding that multiculturalism reflects the freedom of all members of Canadian society to preserve, enhance and share their cultural heritage . . . j) advance multiculturalism throughout Canada . . .” In the Charter of Rights and Freedoms it states: “Multiculturalism is a central feature of Canadian citizenship . . . The federal government has the responsibility to promote multiculturalism throughout its departments and agencies.” By now it may have become quite apparent to some readers that * Canada does have a proclaimed state ideology, a civil religion with a set of values desired of all citizens, which it calls.. multiculturalism. We do not have to be sad or mad, or be sorry to discover this. The only thing we have to know is: What is this civil religion and what are its doctrines and are they achieving the desired goals set in the act?

UNFORTUNATELY IT is unclear what the word “multiculturalism” means precisely. As the Minister for Multiculturalism and Citizenship, Gerry Weiner, explained recently (through his executive assistant), “There is no official government-of-Canada definition of the term ‘multiculturalism.’ “

THUS, THOUGH WE do have a state dogma, a civil religion for at least non-French Canada, we still have to discover its exact tenets. We need to know more precisely what it means before we can put our faith in these beliefs.

DOB 19891017UPDATE 960728NDATE 19891017NUPDATE 19960728..