Everything has gone from the world,

The world has become empty again.

Human animal.

Humanity animality.

Everything has gone from the world,

I don’t see anything now.

All that I see is

My imagination.

They don’t accept us as humans,

They don’t accept us as animals either.

And, as they would say,

Humans have two dimensions.

Humanity and animality,

We are out of both of them today.

So begins Samiullah Khalid Sahak’s poem Humanity. It is a poem about the pitilessness of war and of its destruction of human sensibility, indeed of human identity. It is also a poem by a supporter of the Taliban.

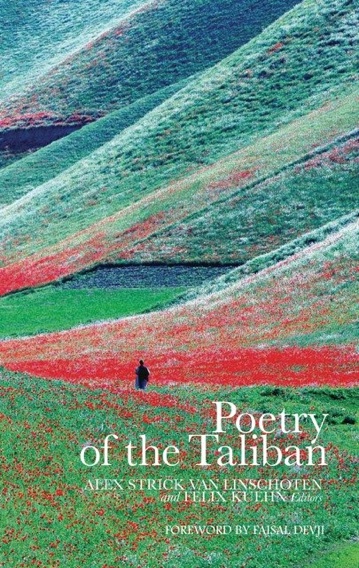

Sahak’s poem is one in a new anthology of the Poetry of the Taliban collected and edited by Alex Strick van Linschoeten and Felix Kuehn, two Kandahar-based researchers and writers. There is something deeply unsettling, indeed shocking, about talking of ‘the poetry of the Taliban’. After all, the Taliban is better known for its savagery and suicide bombings, for throwing acid at the faces of girls attending school, than for its aesthetic sense. Its arts policies include the demented act of blowing up the Bamiyan giant stone Buddhas and the banning of music (though it is said that the Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar ignores his own edict and listens to music tapes in his car.)

Many, inevitably, have denounced the publication of the anthology. Colonel Richard Kemp, a former British commander in Afghanistan, denounced the collection as ‘self-justifying propaganda’. ‘What we need to remember’, he insisted, ‘is that these are fascist, murdering thugs who suppress women and kill people without mercy if they do not agree with them… It doesn’t do anything but give the oxygen of publicity to an extremist group which is the enemy of this country.’

Such anger may be understandable, especially set against some of the gushing liberal responses to the anthology. The writer William Dalrymple praised the collection for ‘humanising and giving voice to the aspirations, aesthetics, emotions and dreams of the fighters of a much-caricatured and still little-understood resistance movement’. Jon Lee Anderson, a staff writer for the New Yorker, thought the Taliban too ‘harshly perceived’ when it contains ‘warriors who have wounded hearts, lyrical souls, and a passionate love of language’. Poetry of the Taliban, suggests James Caron, lecturer in South Asian Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, restores to the ‘insurgent’ a ‘sense of humanity and agency’.

One does not have to support the war in Afghanistan to find abhorrent such apologia for the Taliban. As one commentator sardonically observed about these responses, ‘it’s nice that liberals finally have pro-war voices they can rally around.’

Somewhere between Kemp’s refusal to acknowledge the poetry and the liberal romanticisation of the poets lies a rational response to an anthology such as this. Kemp is right that the Taliban is savage, vicious and brutal. He is right, too, that it will try to use an anthology such as this for propaganda purposes. But neither the character of the Taliban nor the uses it might try to put this collection, should lead us to ignore Poetry of the Taliban.

The relationship between art and propaganda is complex, as is the relationship between a work of art and the political beliefs and actions of its creator. From Stalin’s promotion of socialist realist art to the CIA’s sponsorship of Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko exhibitions, from the Nazis’ exploitation of Leni Riefenstahl’s films to the war artists employed by the British army, governments have always tried to use art for political purposes. But art – certainly art of any merit – can never be reduced to mere propaganda. There is always tension between its function as a work of art and its function as a work of propaganda. And out of that tension we can gain insight into both the art and the political and cultural soil from which it emerged.

Afghanistan is a nation with a fine literary, especially poetical, tradition reaching back centuries. It is not surprising that a movement even such as the Taliban should inspire poetry, though there is little in this anthology that aspires to the heights of that tradition. There is much that is absurdly militaristic and bombastic, almost caricatures of what Taliban poetry might look like:

Mother! Pray for me, I am going into battle tomorrow;

I am going for Allah’s satisfaction, without delay;

Battle has many rewards; Allah will grant me paradise’

(Abu Fazl, ‘A Mujahed’s Wish From His Mother’).

We are the soldiers of Islam and we are happy to be martyred;

We are the men of the battlefield and we fight on the front lines.

(Ramani, ‘We are the Soldiers of Islam’).

I will murder all the enemies of your religion and prosperity,

I will gradually make you the holy necklace of Asia.

May I be sacrificed, sacrificed for your hot trenches

(Habibi, ‘May I be sacrificed for you my homeland’)

Such verses are about as subtle as a suicide bomb. It is here that the anthology descends closest into being mere propaganda. It is also here that it is least effective as propaganda, precisely because the poetic sentiments are so crass.

There is, thankfully, more to Poetry of the Taliban than simply such asinine anthems of war. War certainly haunts this collection, not just the current war but the history of invasion and war in Afghanistan. But beyond the drumbeats for martyrdom are more evocative poems about the pity and sorrow of conflict, such as Sahak’s lament about his nation’s loss of humanity.

And yet, a poem like Humanity reveals also the hollowness at the heart of this collection. What is missing is any sense of self-reflection or criticism, any trace of challenge or dissent, any perception that the loss of humanity might have come from within. One does not expect in an anthology such as this any overt condemnation or denigration of the Taliban – it is, after all, poetry of the Taliban and therefore self-selected. One might expect, especially in a collection of poetical responses to war, a sense of the damage that has been wrought from within as well as from without. A single poem, ‘Self-made prison’ looks within:

It’s a pity we are wandering as vagrants,

We did all of this to ourselves.

Those two lines stand almost alone as a flash of doubt within an anthology in which war seems to be experienced in only one of two registers: that of the avenger and that of the victim. There is no hint here of an Afghan equivalent of a Wilfred Owen or a Miguel Hernandez.

War may be the dominant theme in this collection. It is not, however, the only theme. There are pastoral poems, paens to the Afghan landscape, and love poems, often earthy and lusty. There is little Talibanesque about them. Rather they draw upon ideas, forms, metaphors and allusions that are universal, to be found in almost any culture, not least in the cultures of the West. It is here that the anthology is most revealing: not as a window on the Taliban but as a bridge to the wider world.

The significance of the anthology is not that it helps humanize the Taliban – after all, what are Taliban fighters if not human beings? – but that it reveals the complexity of human cultures. A culture that can produce a movement as savage and brutal as the Taliban can produce also a finely-tuned poetic sensibility. That should not surprise us, for cultures are never all or nothing affairs. Every culture produces a host of different and often contradictory sensibilities. The history of Western societies tells us that. The Europe of Michelangelo and da Vinci was also the Europe that burnt witches and heretics by the score. The England that produced Shakespeare was also the England that transported millions of Africans into slavery.

Blindness to the variegated character of cultures and movements has been one of the hallmarks of the West’s ‘war on terror’, expressed most clearly in the perception of that war as the product of a ‘clash of civilizations’. It has, ironically, also helped create the Taliban as it is now. In an earlier book An Enemy We Created, van Linschoeten and Kuehn tell the story of how the American insistence that al Qaeda and the Taliban were in effect a single, unified enemy, and the US view of the Taliban as just another jihadist group, helped conjure up that very mythical enemy that Washington so feared. The Taliban was originally an inward-looking, brutally conservative, local Afghan movement, governed by a literal reading of the Qu’ran, but with no visions of global jihad, and indeed with a desire to seal itself off from the outside world. Al Qaeda comprised mainly Arab fighters, with virtually no roots in any society, and driven by a fantasy desire to unify the ummah and spark a global jihad against the West. There was little in their beliefs and aims and attitudes to unite the two groups and much to separate them. One of the striking aspects of Poetry of the Taliban is that for all the bloodcurdling bravado that infuses the much of the collection, there is no mention here of al Qaeda or Osama bin Laden or jihad or the global ummah. But through its crass inability to recognize the fundamental political and cultural differences between the two groups, the West helped bring al Qaeda and the Taliban much closer together and transformed the Taliban into a far harder, more belligerent, more ideologically-driven group.

If the variegated reality of cultures poses a challenge for Western perceptions, it poses an even greater one for the Taliban. Poetry has played an important part in moulding identity, whether Afghan, Taliban or Pashtun, and in providing a sense of history and tradition. But it also challenges that identity, by fostering links to many histories and traditions, by creating a bridge – by creating many bridges – to a wider world. However much a movement like the Taliban might insist that it is creating a ‘strict’ Islamic culture, sealed off from evil foreign influences, the very nature of cultures undermines that project. And however much it might want to use it as a work of propaganda, an anthology like Poetry of the Taliban will also always be a missile aimed at the heart of the Taliban’s perception of Islam, of the West and of the war that it is waging.

I LOVE your blog! Just felt like I’d been silently reading it without saying thanks for too long. Thank you 🙂 So many shared posts and such a clear point of view that has helped me with my own thoughts.

“The significance of the anthology is not that it helps humanize the Taliban but that it reveals the complexity of human cultures. A culture that can produce a movement as savage and brutal as the Taliban can produce also a finely-tuned poetic sensibility.”

I think this is the vital point here and you set the situation perfectly. Important words about a political group that is little understood and even less liked globally.