‘Solidarity and anger. Those were my immediate emotions’. So I wrote last November after the Paris attacks: ‘Solidarity with the people of Paris, anger at the depraved, nihilistic savagery of the terrorists.’ My emotions are much the same after the savage attacks in Brussels this week. ‘But, beyond solidarity and anger,’, I observed in November, ‘we need also analysis.’ I have written much over the past few years about why conventional views about radicalization and the making of European jihadis are wrong. So here, some of the main themes of my articles on jihadism.

1

Contemporary terror attacks are not responses to Western foreign policy. What marks them out is their savage nihilistic character

Terrorists often claim a political motive for their attacks. Commentators often try to rationalize such acts, suggesting that they are the inevitable result of a sense of injustice created by Western foreign policy or by anti-Muslim attitudes in the West. Yet most attacks have been not on political targets, but on cafes or trains or mosques. Such attacks are not about making a political point, or achieving a political goal – as were, for instance, IRA bombings in Britain in the 1970s and 1980s – but are expressions of nihilistic savagery, the aim of which is solely to create fear. This is not terrorism with a political aim, but terror as an end in itself.

After Paris, 15 November 2015

The trouble with much of the discussion of terrorism today is that it misses a fundamental point about contemporary terror: its disconnect from social movements and political goals. In the past, an organisation such as the IRA was defined by its political aims. Its members were carefully selected and their activities tightly controlled. However misguided we might think its actions, there was a close relationship between the aims of the organization and the actions of its members. None of this is true when it comes to contemporary terrorism. An act of terror is rarely controlled by an organisation or related to a political demand. That is why it is so difficult to discern the political or religious motivations of the Tsarnaev brothers. They neither claimed responsibility nor provided a reason for their actions. It was not necessary to do so. The sole point was to kill indiscriminately and to spread fear and uncertainty. Far from being part of a political or religious movement, what defines terrorists like the Boston bombers is their very isolation from such movements.

Reasoning about terror, 2 May 2013

2

We should reject the attempts to link terror attacks to the migration crisis and the failure to close borders

The problem of terrorism in Europe has not been created by terrorists smuggling themselves onto refugee boats. It has, rather, mostly been the work of homegrown jihadis. The Kouachi brothers, for instance, responsible for the Charlie Hebdo killings in January were born and raised in Paris. So was Amedy Coulibaly, the gunman who, that same weekend, attacked a kosher supermarket in Paris and killed four Jews. Three of the four suicide bombers responsible for the 7/7 attack on London tubes and a bus were similarly born in Britain. Most of the 4000 or so Europeans who have joined IS as fighters have been European-born, and many have been professionals, and well integrated into society.

Pointing the finger at refugees not only sidesteps the problem of homegrown jihadism, it also foments more anti-immigrant hatred, further polarizing European societies.

After Paris, 15 November 2015

3

Both sides in the debate about the relationship of terror to Islam miss the point

For some the answer lies with Islam itself. ‘There’s a global jihad lurking within this religion’, the Canadian journalist Mark Steyn insists. Islam is ‘a bloodthirsty faith in which whatever’s your bag violence-wise can almost certainly be justified.’

Others have resisted the idea that jihadism is driven by Islam. David Cameron, in an interview on Radio 4’s Today programme in the wake of the slaughter of tourists on Sousse beach in Tunisia, condemned those who call Islamic State ‘Islamic State’. It is ‘not an Islamic State’, he claimed because ‘Islam is a religious of peace’.

Neither argument possesses credibility. A religion is defined not just by its holy texts but also by the ways in which believers interpret and act upon them; that is, by its practices. The fact that supporters of IS practice their religion in a way that horrifies the British Prime Minister, and most liberals, and indeed, most Muslims, does not make it any less real or Islamic. Like it or not, Islamism is an integral part of the tapestry of contemporary Islam.

And yet, while the insistence that jihadism is disconnected from Islam makes little sense, the claim that Islam can explain why jihadis act so unconscionably is equally untenable. The vast majority of Muslims, after all, abhor the actions of IS, and would find their actions morally inexplicable. Nor is it just Islamists who are drawn into such acts. From Buddhist monks in Myanmar organizing pogroms against the Rohingya to Dylann Roof shooting dead nine worshippers at the Emanuel African church in Charleston, inhumanity is widespread in the non-Muslim world too.

Evil and the Islamic State, 16 July 2015

Contemporary radical Islam is the religious form through which a particular kind of barbarous political rage expresses itself. So rather than debate ‘Is Islam good or evil?’ or ‘Are jihadis motivated by politics or religion?’, we need to ask different kinds of questions, about both religion and politics. Why does political rage against the West take such nihilistic, barbaric forms today? And why has radical Islam become the principal means of expressing such nihilistic, barbaric rage?

Radical Islam and the rage against modernity, 28 January 2015

4

Conventional arguments about ‘radicalization’ are wrong

The conventional radicalization narrative consists broadly of four elements: First, the claim that people become terrorists because they acquire certain, usually religiously informed, extremist ideas. Second, that these ideas are acquired in a different way to the way people acquire other extremist or oppositional ideas, such as , say, Marxism or anarchism, or mainstream ideas such as conservatism or liberalism Third, that there is a ‘conveyor belt’ that leads from grievance or personal crisis to religiosity to the adoption of radical beliefs to terrorism And, fourth, the insistence that what makes people vulnerable to acquiring such ideas is that they are poorly integrated into society. There is, however, little evidence in support of any of these four elements of radicalization, and considerable evidence to suggest that all are untrue.

Many studies show, for instance, perhaps surprisingly and counter-intuitively, that those who are drawn to jihadi groups are not necessarily attracted by fundamentalist religious ideas. There is also little evidence that jihadists acquire their ideas differently from the way people may acquire other kinds of ideas. Nor is there any evidence of a conveyer belt leading people from radical ideas to jihadist violence. And finally, there is much evidence that those who join jihadi groups are anything but poorly integrated, at least in the conventional sense of looking at integration.

Radicalization is not so simple, 7 October 2015

5

We are often asking the wrong questions when it comes to radicalization

Those drawn to groups such as Islamic State are certainly both politically enraged about Western imperialism and have a very particular view of Islam. Religion and politics both form indispensible threads to their stories. And, yet, the ‘radicalization’ argument, whether stressing push or pull factors, whether prioritising religion or politics, looks upon the jihadists’ journey back to front. It begins with the jihadists as they are at the end of their journey – enraged about the West, with a back and white view of Islam, and a distorted moral vision – and assumes that those are the reasons that they have come to be as they are. But if we look at the stories of wannabe jihadis, the first steps on their journeys to Syria are rarely taken for political or religious reasons.

Radicalization is not so simple, 7 October 2015

What draws young people (and the majority of would-be jihadis are in the teens or in their twenties) to jihadi violence is a search for something a lot less definable: for identity, for meaning, for belongingness, for respect. Insofar as they are alienated, it is not because wannabe jihadis are poorly integrated, in the sense of not speaking the local language or being unaware of local customs or having little interaction with others in the society. Theirs is a much more existential form of alienation.

Radicalization and European social policy, 17 December 2015

There is, of course, nothing new in expressions of alienation and angst. The youthful search for identity and meaning is almost a cliché. What is different today is the social context in which such alienation and such a search occurs. We live in a far more atomized society than in the past; in an age in which there is a growing sense of social disintegration and in which many people feel peculiarly disengaged from mainstream social institutions; and, in which, for many, moral lines seem blurred, identities distended, and conventional culture, ideas and norms detached from their experiences.

Radicalization is not so simple, 7 October 2015

6

Part of the reason for the reason for the attraction of jihadism in Europe is that the collapse of the left, and of a universalist outlook, has combined with the rise of identity politics to create new openings for Islamism

What gives shape to contemporary disaffection is not progressive politics but the politics of identity. Identity politics has, over the past three decades, encouraged people to define themselves in increasingly narrow ethnic or cultural terms. A generation ago, today’s ‘radicalised’ Muslims would probably have been far more secular in their outlook, and their radicalism would have expressed itself through political organizations. Today they see themselves as Muslim in an almost tribal sense, and give vent to their disaffection through a stark vision of Islam.

The making of wannabe jihadis in the West, 1 March 2015

Being ‘community minded’ clearly meant something very different to the Mullah Boys than it had to the Asian Youth Movement. The identity of the AYM, and of its members, came from its political vision, and from its relationship to broader political movements, working class organisations at home and national liberation struggles abroad. ‘The only real movements capable of fighting the growth of organised racism and fascism’, the Bradford AYM declared in its magazine Kala Tara, ‘is the unity of the workers movement black and white.’ The AYM also saw the fight against racism as part of a wider set of struggles such as those ‘in Ireland, South Africa, Zimbabwe and Palestine’. Those struggles (like the AYM itself) had all but disappeared by the 1990s; not just physically in the sense of the decline of the organisations but intellectually, too, as the ideas that had fired those movements burned out.

A decade earlier Sidique Khan or Shehzad Tanweer might well have joined the AYM, or even the Socialist Workers Party. But these were now lost causes. Far from being plugged into a wider political network, as the AYM had been, the Mullah Crew existed primarily because its members were cut off from wider society. Their aim was not to change the world but to protect their turf on the streets of Beeston. In that difference – in the degeneration of political campaigning into gang ritual – lies much of the change that has taken place within Muslim communities in Britain over the past twenty years. And out of that difference have come the reasons that a number of Muslims have turned jihadist.

The making of a British jihadi, 6 June 2013

7

The fading of the left and the rise of identity politics has also transformed anti-Western sentiment and turned it into an inchoate rage against modernity

Anti-imperialists of the past saw themselves as part of a wider political project that sought to modernize the non-Western world, politically and economically. Today however, that wider political project is itself seen as the problem. There is considerable disenchantment with many aspects of ‘modernity’ from individualism to globalization, from the breakdown of traditional cultures to the fragmentation of societies, from the blurring of moral boundaries to the seeming spiritual soullessness of the contemporary world.

In the past racists often viewed modernity as the property of the West and regarded the non-Western world as incapable of modernizing. Today, it is ‘radicals’ who often regard modernity as a Western product and reject both it and the West as tainted goods.

The consequence has been the transformation of anti-Western sentiment from a political challenge to imperialist policy to an inchoate rage about modernity. Many strands of contemporary thought, from the deep greens to the radical left, express aspects of such discontent. But it is radical Islam that has come act as the real lightning rod for this fury.

Radical Islam and the rage against modernity, 28 January 2015

The demise of traditional opposition movements has led many to look for alternative forms of struggle, and created a yearning for God-given moral lines. Islamism, with its demand for a struggle to establish an alternative system governed by divinely-sanctioned rules, has for some filled the void. The illusion of divine sanction has allowed jihadis to justify their acts, however grotesque they may be.

Jihadis imagine that they are waging war against the West. But the West has become in their eyes, not a set of specific nations responsible for specific acts, but an almost mythical, all-encompassing monster, the modern version of the chimera or basilik, the source of all manner of horror and dread. And against such a monster, almost any act becomes acceptable.

Shorn of the moral framework that once guided anti-imperialists, shaped by black and white values that in their mind possess divine approval, driven by a sense of rage about non-Muslims and a belief in an existential struggle between Islam and the West, jihadis have come to inhabit a different moral universe, in which they are to commit the most inhuman of acts and view them as righteous.

Why do jihadis seem so evil? 22 November 2015

8

Muslims are not the only group to feel disaffected and estranged from mainstream institutions. There is, however, something distinctive about Islamist identity

These developments have shaped not just Muslim self-perception but that of most social groups. Many within white working communities are often as disengaged as their Muslim peers, and similarly see their problems not in political terms but rather through the lens of cultural and ethnic identity. Hence the growing hostility to immigration and diversity, and, for some, the seeming attraction of far-right groups. Racist populism and radical Islamism are both in their different ways expressions of social disengagement in an era of identity politics.

The making of wannabe jihadis in the West, I March 2015

European societies have in recent years become both more socially atomized and riven by identity politics. Not just the weakening of labour organizations, but the decline of collectivist ideologies, the expansion of the market into almost every nook and cranny of social life, the fading of institutions, from trade unions to the Church, that traditionally helped socialize individuals – all have helped create a more fragmented society.

At the same time, and partly as a result of such social atomization, people have begun to view themselves and their social affiliations in a different way. Social solidarity has become defined increasingly not in political terms – as collective action in pursuit of certain political ideals – but in terms of ethnicity or culture. The question people ask themselves is not so much ‘In what kind of society do I want to live?’ as ‘Who are we?’. The two questions are, of course, intimately related, and any sense of social identity must embed an answer to both. The relationship between the two is, however, complex and fluid.

As the political sphere has narrowed, and as mechanisms for political change eroded, so the two questions have come more and more to be regarded as synonymous. The answer to the question ‘In what kind of society do I want to live?’ has become shaped less by the kinds of values or institutions we want to struggle to establish, than by the kind of people that we imagine we are; and the answer to ‘Who are we?’ defined less by the kind of society we want to create than by the history and heritage to which supposedly we belong. Or, to put it another way, as broader political, cultural and national identities have eroded, and as traditional social networks, institutions of authority and moral codes have weakened, so people’s sense of belonging has become more narrow and parochial, moulded less by the possibilities of a transformative future than by an often mythical past. The politics of ideology has, in other words, given way to the politics of identity.

Populism: What, why, how?, 5 November 2014

Because Islam is a global religion, so Islamists are able to create an identity that is both intensely parochial and seemingly universal, linking Muslims to struggles across the world and providing the illusion of being part of a global movement. Islamism, like all religiously-based ideologies, provides, too, the illusion of divine sanction for jihadists’ acts, however grotesque they may be.

Isolated from wider society, disembedded from social norms, shaped by black and white values which in their mind possess divine approval, driven by a sense of rage about non-Muslims and a belief in an existential struggle between Islam and the West, jihadis are able to commit the most inhuman of acts and to view them as acceptable, even righeous.

Evil and the Islamic State, 16 July 2015

9

Jihadis are often as estranged from mainstream institutions of Islam as they are from wider society.

Most homegrown wannabe jihadis possess a peculiar relationship with Islam. They are, in many ways, as estranged from Muslim communities as they are from Western societies. Most detest the mores and traditions of their parents, have little time for mainstream forms of Islam, and cut themselves off from traditional community institutions. Mohammed Siddique Khan, the leader of the 7/7 bombers, is a classic case in point. He had rejected his parents’ subcontinental traditions, refused an arranged marriage, and wed instead Hasina Patel, a woman he had met at university. So disgusted was Khan’s family with his love-match that it all but disowned him. Disengaged from both Western societies and Muslim communities, some reach out to Islamism. They rarely arrive at Islamism by attending sermons given by preachers of hate. Rather, such ideas usually percolate through small groups of friends in gyms or youth clubs. Again, the 7/7 bombers are a case in point. It was in a gym that Siddique Khan met with two of the other bombers, Shezad Tanweer and Hasib Hussain to sketch out the plans for the bombings.

What Islamism provides to those drawn to it is not religion in any old-fashioned sense, but identity, recognition and meaning. Detached from traditional religious institutions and cultures, many adopt a literal reading of the Qur’an and a strict observance of supposedly authentic religious norms to mark themselves out as distinct and provide a collective identity.

Myths of radicalisation, 2 June 2013

Radicals have a loose or no connection with Muslim communities in Europe… Investigators and journalists who immediately meet the family and the entourage of the attacker are told the same story: he was a quiet, nice boy (variation: he was just a petty delinquent), and he was not pious, drank alcohol, had girls etc, except that, recently his attitude has drastically changed…

Few of them were regular ‘parishers’ in a local mosque. None of them was active in religious activities (proselytism): when they preach Islam it is to recruit other radicals, not to spread the good news…

When they join jihad, they adopt the Salafi version of Islam, because Salafism is both simple to understand (don’ts and do’s), and rigid, providing a personal psychological structuring effect. Moreover, Salafism is the negation of cultural Islam, that is the Islam of their parents and of their roots. Instead of providing them with roots, Salafism glorifies their own deculturation and makes them feel better ‘Muslims’ than their parents. Salafism is the religion by definition of a disenfranchised youngster…

Olivier Roy on European Jihadis, 10 December 2015

Multicultural policies in the 1980s had helped create a more tribal Britain by encouraging people to see themselves in narrower ethnic or cultural terms. Muslim inhabitants of towns such as Beeston adopted a more rigid Islamic identity, becoming more isolated from other communities in the town. Second generation Muslims like the Mullah Boys would, just a decade earlier, have probably been far more secular in their outlook, and more willing to forge friendships with people of different faiths and cultures. Now they saw themselves as tribal Muslims and most of the people they knew, liked and trusted came from within the tribe. But not only were segregated from the wider social world, they were also cut off from the traditional institutions and structures of Islam. Even though the Boys saw themselves as Muslim, they wanted nothing to do with the subcontinental Islam of their parents. In challenging the old ways, they isolated themselves from their families and often became pariahs in the community. So disgusted were Sidique Khan’s family about his relationship with Hasina Patel [a woman he had met at university and whom he had married, having refused a match arranged by his parents] that they moved from Beeston to Nottingham, in the hope that their errant son would follow them. He didn’t.

It is a common story. In The Islamist, Ed Husain tells of how his attraction to radical Islam led to a battle with his pious but traditional father. Eventually his father gave him an ultimatum: leave Islamism or leave my house. Husain decided to leave his house. He stole out in the middle of the night and crept down to the East London mosque, which was controlled by the Jamaat-influenced Islamic Forum. He was taken in by ‘the brothers’ and treated like a ‘family member’. For people like him, Husain observes, ‘cut off from Britain, isolated from the Eastern culture of our parents, Islamism provided us with a purpose and place in life.’

The making of a British jihadi, 6 June 2013

10

It is our response that will determine whether the terrorists succeed

The aim of terror is to terrorize. That may seem too obvious to have to say it, but so much policy response to terrorism seems to ignore that self-evident truth. Many counter-terror policies – banning organizations, censoring speech, extending surveillance – undermine liberties without addressing the issues that has made Islamism attractive to some in the first place. At the same time, they have helped entrench a climate of fear and suspicion, just the kind of climate off which terrorists feed.

The Brussels bombing – just like the Istanbul bombing last week, and the Paris attacks last year – shows how easy it is to cause mayhem and disruption in an open, urban, society. It is the arbitrary nihilism of Islamic terrorism that makes it so terrifying. But that is also its weakness. Terrorists depend for success not just on their actions but on our response. That response should begin with the refusal to create a more illiberal, fearful, suspicious, locked-down society. The solidarity and openness shown by the people of Brussels this week, and of Istanbul last week, is a good starting point.

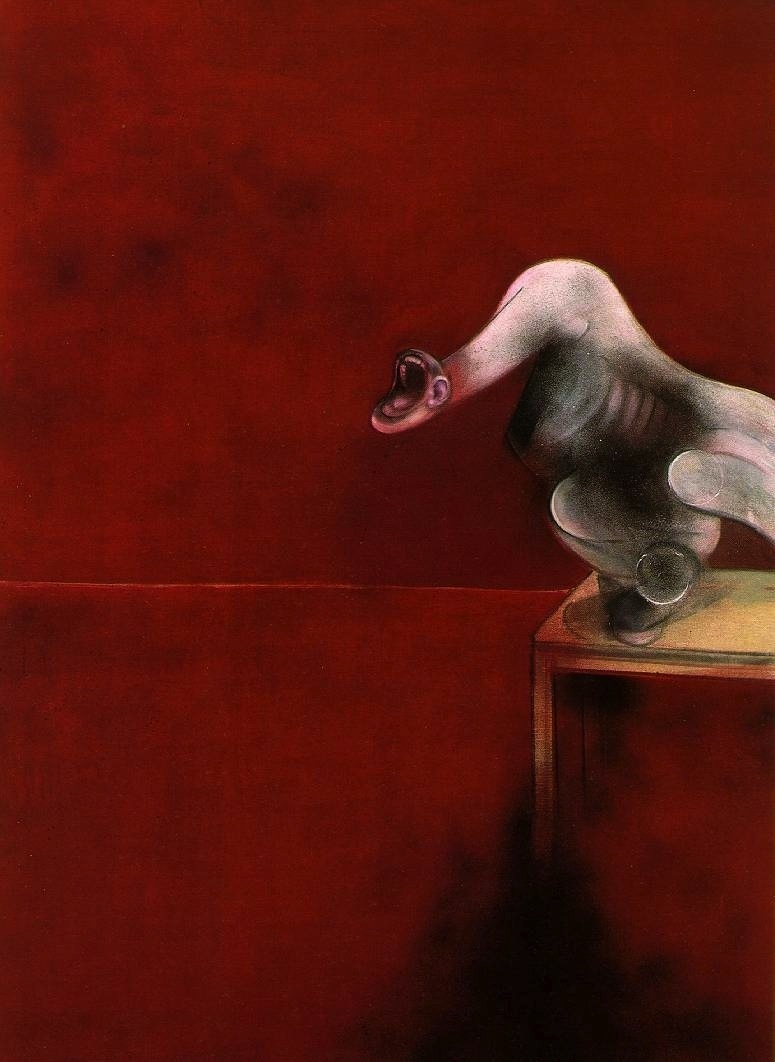

The images are Pierre Soulages, Untitled; Francis Bacon’s Triptych; Salvador Dalí’s ‘The Face of War; Zdzislaw Beksiński’s ‘We are all in the hands of Goliath’.

Thank you. This needs re-reading again and again, to grasp it all. Where can one find a list of the artworks you use here? Profoundly moving .

Thank you. I always reference the artworks I use at the bottom of an article.

LBC (London) radio’s Ian Collins went to Paris last week to record a piece which they will be airing this Sunday night from 10pm.

He was talking about it last night on his show, about how they’d gone to see how the migrant crisis was affecting Paris. He described being outside one metro station north of the Gare due Nord – which sounded to me like the station called ”Barbes- Rochencourt” and how outside it there were so many young men from north Africa that he felt concerned for his safety.

I’ve seen this place myself, so knew what he was talking about.

A mile down the road there was a place where actual asylum seekers were camping and there he felt much safer. They were like totally different people in their group identities.

It’s all a biit complex and nuanced, but the former group are the kind that are easily turned to petty criminality, and perhaps Islamic fundamentalism, while the others down the road just want a better future.

Although the radio presenter is a bit populist and right wing, he is onto something I think.

You mention the trend towards a far more atomized society. I see that we’ve lost some social institutions but Reddit, Twitter, Facebook etc go some way to replacing them. Do you think the problem is that the internet allows us too much freedom to choose our ‘friends’? Before, we had to make do with neighbours, who probably wouldn’t share our enthusiasm for particular ideas, and this kind of damped things down, made us more rounded. Whereas now, we can find forums with people who reinforce our own beliefs and that makes it seem less ridiculous when those interests turn into obsessions? I wonder if we always had the internet, would we always have had jihadis. Maybe there were always people with those tendencies, and now they can just find each other.

“…but are expressions of nihilistic savagery, the aim of which is solely to create fear. This is not terrorism with a political aim, but terror as an end in itself.”

You could just as well be describing what the US has been doing in the Middle East for the past 13 years. Killing people for no reason whatsoever. Just because we can. The fact of the matter is that we are in a fight to the death with these nihilistic Muslims you mention, who are sick and tired of being bombed and tortured by nihilistic Americans. It’s going to be a fight that lasts…forever, as far as everyone alive is concerned.

You went to the heart of the matter. I wonder why this most central point is ignored or not understood in this article. This is as political as anything gets. Terrorists are sending a clear message, just as clear of a message as Western countries when they do vast harm in the Middle East. It’s just not what ordinary people have been taught to recognize as politics.

But (as Malik discussed elsewhere) the admittedly barbaric treatment of the UAE by the US took place some time ago. How about this? These terrorists are no simple bearer of messages, outraged by this historical treatment. Instead, they are motivated by something less defined, less controllable and infinitely darker than the ‘avenger of the US treatment of the UAE’. The profile of this present terrorist is not as A describes ‘these nihilistic Muslims you mention, who are sick and tired of being bombed and tortured by nihilistic Americans’ but another breed of already disenfranchised young people in our European countries who are reaching for the grievance along the way. The motivation is the savage destruction of ‘normal’ life going on around them in Europe, of which they assume no part, which is the ‘end’ they wish to achieve. The message is perhaps too simple in its darkness, too random and uncontrollable, and certainly too uncomfortable for us to accept.

Anyone who has been paying attention in the slightest knows that Western countries have been continuously meddling in the Middle East for a long time. That is true at this very moment. Besides direct attacks and covert manipulations, we are also allied with and support countries like Saudi Arabia and Israel, two countries with well known reputations as oppressive. This is common sense, for those who have common sense. The only darkness we need to confront is the willful ignorance of too many Westerners.

I am always struck by the desire of so many to rationalize nihilist terror, and to impute to savagery a moral or political purpose it does not possess.

Fewer than 5 per cent of people killed by jihadists are in the West. The vast majority of the remaining 95 per cent are Muslims in Muslim-majority countries. I wonder what ‘clear political message’ jihadists are sending to the West about its foreign policy when they slaughter 148 children in a Peshawar school, or kill dozens with a suicide bomb in a market in Beirut, or throw gays off a tower in Syria, or blow up a café in Morocco?

There is nothing new in Western intervention in Muslim-majority countries. From Winston Churchill ordering the use of mustard gas against Iraqi rebels in the 1920s, through the CIA-engineered coup against the democratically elected government of Mohammed Mosaddeq in 1953, to the West’s backing for Saddam Hussein in his war against Iran in the 1970s, and beyond, there is a long history of Western intervention. There has always been resistance to such intervention, often violent resistance, and sometimes the use of terror. But violence and terror were always in the service of specific political aims. Nihilistic terror is new, a product of the breakdown of the old anti-imperialist movements. Anti-Western sentiment has transformed from a political challenge to imperialist policy to an inchoate rage about modernity. As I put it in Why do jihadis seem so evil?:

The kind of nihilistic savagery we’ve seen in Brussels and Paris – and even more in Istanbul and Beirut and Peshawar and Baghdad and Aleppo – is not driven by political impulse but by extinguishing of such impulse, by the marginalization of politically-driven anti-imperialist movements.

Finally, however misguided and even immoral Western interventions may be, to define such interventions as driven merely by the desire to kill as ‘Killing people for no reason whatsoever. Just because we can’ is simply idiotic.

I’m always struck by willful ignorance to rationalize almost everything that is wrong with the world. Pointing to facts is not the same thing as making a moral argument. Only the willfully ignorant think that way.

Most Muslisms are killed by Muslims in Islamic countries. And most Christians are killed by Christians in Christian countries. Brilliant! What’s your next case, Sherlock? What message are Christians sending when they kill other Christians? Maybe religion is just a story people tell for their motivations, but not the actual motivations themselves which have to do with entirely other things: race/ethnicity, social divisions, political ideology, etc.

Seeing terror as ‘nihilistic’ is a subjective perception. People always have their reasons. If you actually want to understand what is new, you’d have to look at facts. People are more desperate than in the past. For example, climate change has sent caused drought in various countries. Globalization has increased over time as well. Plus, the type of weapons used today are different. Constant threat of drone attacks creates a permanent state of terror for entire populations.

Willful ignorance is idiotic. I recommend against. You are a smart guy. And you’re better than this. Your comments here are just ignorant bigotry and quite pathetic at that.

A lot of bluster here, some abuse, but no argument. And certainly no reply to the question I asked. So let me ask it again: I wonder what ‘clear political message’ jihadists are sending to the West about its foreign policy when they slaughter 148 children in a Peshawar school, or kill dozens with a suicide bomb in a market in Beirut, or throw gays off a tower in Syria, or blow up a café in Morocco?

Oh, and do please show me where in anything I wrote lies ‘ignorant bigotry’.

If these were Islamic terrorists, they would be true believers. That is the complete opposite of nihilism:

http://www.iep.utm.edu/nihilism/

“Nihilism is the belief that all values are baseless and that nothing can be known or communicated. It is often associated with extreme pessimism and a radical skepticism that condemns existence. A true nihilist would believe in nothing, have no loyalties, and no purpose other than, perhaps, an impulse to destroy.”

You can dismiss facts as bluster. But that just proves my point. What political point? Ask the terrorists. Everything involves politics, one way or another. That is common sense. Even climate change problems have major elements of politics, specifically in terms of who is most effected.

I know you’re capable of figuring this stuff out. In fact, it’s your job to figure this stuff out and not make dismissive, inane judgments such as ‘nihilism’. That is a non-explanation explanation. I know you can do better than that.

As for ignorant bigotry, it is expressed in your entire attitude in this piece. Your opinion doesn’t express enlightened compassion, that is for sure.

So if I was to go down to my local supermarket, shoot all the customers and claim ‘This is for Syria’, that, in your eyes, would be a genuine political act? Hmm, OK…

That’s what they call a non-sequitur…

You mean you cannot actually show me what was ‘ignorantly bigoted’ in what I wrote – because nothing was – but you just like throwing around insults? Now, what was I saying about bluster?

And finally, let me ask again the question that you have so far twice evaded: What is the ‘clear political message’ jihadists are sending to the West about its foreign policy when they slaughter 148 children in a Peshawar school, or kill dozens with a suicide bomb in a market in Beirut, or throw gays off a tower in Syria, or blow up a café in Morocco?

Anytime religion is applied to the larger society, politics is always involved. The religious adherents who commit various acts, may not think in political terms. Their entire framework might be religious or they might think of it as cultural or whatever. But there are many ways people think of the political. It is for politically-informed scholars and journalists to figure out what the political significance is, the motivations behind the acts.

I can show you that your views stated here are ignorantly bigoted. You are making dismissive generalizations based on a prejudices about another group. You use a non-explanation explanation to shut down debate, instead of offering or even considering some of the basic facts at hand, such as a few that I suggested.

Clear political message? Well, put in context of my full comment. I also spoke of, ” just as clear of a message as Western countries.” So, it’s a relative clarity. I don’t think most citizens and soldiers of Western governments know why Western violence is committed in foreign countries. As with this article, mostly all we hear are dismissive non-explanation explanations. But the message often seems clear to those who are targets of violence. The message is about political power and the ability to enforce it or, in the case of terrorists, the ability to lash out.

Violence is politics by another name. There is always a reason, a motivation behind all human behavior. And for those willing to look, there is always a message to be understood. For one thing, desperate people do desperate things. So, first understand why people are or feel desperate. Violence is the voice of those who feel they have no other voice. What message is in that desperation? A plea to be heard, to be taken seriously, to have their problems acknowledged, to end violent oppression in their home countries, what?

I don’t know. That is your job to figure that out, not to dismiss it.

This is getting tiresome.

Perhaps you can show me. But so far you haven’t. All you have done is talk in generalities and evade the question. It is striking that not once have you been able to quote anything I have written. Quote me. Point specifically to what I have written that is ‘ignorant bigotry’. Show me exactly where I make ‘dismissive generalizations based on a prejudices about another group’. Otherwise just admit that you’re talking bullshit.

Shutting down debate? This is the sixth comment you’ve made on this thread. I’m more than open to debate. I’m still waiting for you to respond in anything other than abstract generalities and not to evade every question I ask of you.

Yet more evasion. You wrote ‘This is as political as anything gets. Terrorists are sending a clear message’. I asked: ‘What [is the] ‘clear political message’ jihadists are sending to the West about its foreign policy when they slaughter 148 children in a Peshawar school, or kill dozens with a suicide bomb in a market in Beirut, or throw gays off a tower in Syria, or blow up a café in Morocco?’ This is the fourth time I have asked. I have yet to receive an answer.

All violence? Let me ask you again another question that you have avoided: If I was to go down to my local supermarket, shoot all the customers and claim ‘This is for Syria’, would that, in your eyes, be a genuine political act?

Yes there is. And I have through many articles developed an argument about what it is that creates the forms of nihilist violence that we see today. I have quoted from two above: Why do jihadis seem so evil? and Radical islam and the rage against modernity.

I doubt if I have ‘figured it out’ but I certainly have a thesis as to why contemporary jihadist violence takes the form it does. It’s the one you’ve been railing against. Your ‘I don’t know. That is your job to figure that out’ plea seems to mean that you want to rail against my argument, you can’t figure out how, so you reckon it’s my job to work out for an argument against my argument. That’s in keeping with the rest of this thread.

“Perhaps you can show me. But so far you haven’t.”

Perhaps you can make a valid argument based on evidence, instead of dismissing it. But so far you haven’t. I’m simply pointing out that you are ignoring so much and refusing to explain it.

Saying ‘nihilist’ is a non-answer. It is simply to claim that someone’s behavior is meaningless. Yet just as validly someone could claim your argument is meaningless, as you offer no evidence that these terrorists have ever claimed to be nihilist. It’s just empty speculation, which would be fine if you admitted that was what it is.

“All you have done is talk in generalities and evade the question.”

That is because your argument here is generalities. And I’m responding to those generalities. My criticism is that you have to deal with the specifics and I even gave you some examples of the types of specifics you’d need to consider and try to understand.

“Show me exactly where I make ‘dismissive generalizations based on a prejudices about another group’. Otherwise just admit that you’re talking bullshit.”

I’m not talking bullshit any more than you are. You were rude and dismissive. Are you surprised that someone responds to you in kind? All you’ve been doing is opinionating. So, I offered my opinions. But everyone has opinions. That isn’t debate. Your claim of ‘nihilism’ doesn’t take anything or anyone seriously. It shuts down discussion.

“Shutting down debate? This is the sixth comment you’ve made on this thread. I’m more than open to debate. I’m still waiting for you to respond in anything other than abstract generalities and not to evade every question I ask of you.”

It shuts down because you refuse to engage with anything beyond speculation. You make many claims and offer no evidence for any of them. You simply declare your conclusions without building up with careful analysis of evidence. Projecting your generalities onto me doesn’t solve that problem. I offered you specifics such as droughts. But you refuse to even acknowledge any of it.

“Yet more evasion.”

Now you’re just playing games. I explained to you that ‘clear’ is a relative concept. I think Western countries meddling in the Middle East is clearly political, just as responses to it are also clearly political. This is obvious to most informed people. That isn’t evasion, except by you in your refusal to deal with it.

” And I have through many articles developed an argument about what it is that creates the forms of nihilist violence that we see today.”

Maybe you do or maybe you don’t. In the two articles you linked, you offer no evidence for ‘nihilism’. You speculate about it and offer conclusions. That is fine as far as it goes, but it doesn’t seem to go very far. You have a hypothesis. It’s an interesting hypothesis. Now you need to gather evidence to support it.

Part of my problem here is that you seem to pulling pages from the right-wing playbook. Allegations of nihilistic terrorism and outrage sound like right-wing allegations of moral relativism or something like that. What is this supposed nihilism? Do you have any quotes from terrorists demonstrating that they deny all religious meaning and political motivation? You seem to think you know the secret intentions hidden in the souls of terrorists, that your theory about their intentions trumps all else.

I think we must inhabit different universes. Are you serious suggesting that I have evaded all your points rather than try to engage with them, or at least with some of them? Or that you have engaged any of my questions or provided even the slimmest of evidence for your serious claim that my comments amount to ‘ignorant bigotry’? Scratches head in genuine puzzlement. OK, it’s obviously pointless taking this any further so I will leave it at that and end this here.

Muhammad’s acts of ethnic cleansing and genocide (etc), were they all about the West (i.e. me me me) too?

Might the Islamists usher in a wave of the Islam of the future especially if the West reacts too violently and clumsily?

Marginal groups often serve as forerunners and we may be living in an age of flux

For some reason I was more affected by the beating given to a club bouncer here in the States. A group of people beat him even after he was down and it is said he had hit his head when he fell so was actually dead while they continued to beat him. It seems to me that there is an element of madness in all of these acts of violence that has not existed before. We don’t need a reason or a cause, we have simply chosen to go mad, because we can. Of course, this is a much more simple explanation than the thoughts posted and I actually agree with you Kenan Malik, I just also have another way of looking at the problems in the world today. Rather than feeling anger though, I feel sick to my stomach, I think it is sadness. Thanks for your post and for my opportunity to comment.

Benjamin David Steele, I think you know a word called ‘ psychopath’. Psychopaths are inherently evil, characterized by enduring antisocial behavior, diminished empathy and remorse. Their actions are nihilistic. You can say that derive pleasure from afflicting pain on others, and that is the reason they are psychopaths. But, to a sound society, their acts are nihilistic, which means that these barbaric acts have no rational motive of any kind, certainly not political in any way.