This essay was published in the Observer, 19 February 2017.

‘They Kant be serious!’, spluttered the Daily Mail headline in its most McEnroish tone. ‘PC students demand white philosophers including Plato and Descartes be dropped from university syllabus’. ‘Great thinkers too male and pale, students declare’, declared the Times. The Daily Telegraph, too, was outraged: ‘They are said to be the founding fathers of Western philosophy, whose ideas underpin civilised society. But students at a prestigious London university are demanding that figures such as Plato, Descartes and Immanuel Kant should be largely dropped from the curriculum because they are white.’

The prestigious London University was the School for Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). It hit the headlines last month when journalists discovered that students, backed by many of their lecturers, have set up a campaign to ‘Decolonize Our Minds’ by transforming the curriculum. So shocking did the idea seem of a British university refusing to teach Plato or Locke or Kant that the story was picked up by newspapers across the globe. BBC 2’s Newsnight debated whether ‘universities should eschew Western philosophers’. The debate predictably generated more outraged headlines when one of the guests, sociologist Kehinde Andrews, denounced SOAS as a ‘white institution’ and the Enlightenment as ‘racist’.

For academics and students at SOAS, the press coverage itself is the cause of outrage. ‘When the report came out that we were trying to take white men off the table, it was just bewildering because we had no intention of doing that’, says Sian Hawthorne, a convenor of the undergraduate course in ‘World Philosophies’, the only philosophy degree that SOAS provides. ‘Our courses are intimately engaged with European thought’, she adds.

‘We’re not trying to exclude European thinkers’, says a second year doctoral student, and a member of the Decolonizing our Minds group. ‘We’re trying to desacralise European thinkers, stopping them from being treated as unquestionable. What we are doing is quite reasonable.’

So what is the truth behind the headlines? Will philosophy students at SOAS really not be taught Aristotle and Kant? Do the students and academics have a point that the curriculum is too ‘white’? And what should be the place of European philosophy, and European philosophers, in an age of globalization and of a shifting power balance from West to East?

I went to SOAS to talk to students and academics. ‘That’s the one thing’, one student told me, ‘that no journalist has so far done.’

* * * *

The School of Oriental and African Studies was founded in 1916 ‘to secure the running of the British Empire’, as historian Ian Brown puts it in his history of the institution. Its aim was to provide ‘instruction to colonial administrators, commercial managers, and military officers, but also to missionaries, doctors and teachers’. SOAS taught them the local languages as well as providing ‘an authoritative introduction to the customs, religions, laws of the people whom they were to govern.’

Today, of the more than 6000 students at SOAS, almost half come from abroad, from 130 different countries, and more than half are black or minority ethnic. Far from teaching students how to administer the empire, the school now helps develop independent, postcolonial societies. It sees its mission also as providing a critique of empire, and of its continuing legacies, a view that extends to the very top of SOAS management. ‘Our minds are colonized, absolutely’, says Deborah Johnston. ‘In most UK universities there has been a dominance of European thought. That’s why we need to do work to decolonize the curriculum, and our minds.’ Johnston is no student, nor even a mere academic, but the Pro-Director of Learning and Teaching, one of the most senior management figures at SOAS.

For some, such views emanating from the very top of the institution entrench the belief that, in the words of an academic at another London college, ‘SOAS is the most politicized of British universities’. Others, however, see the problem not as an institution that is too politicised but as one that has not yet rid itself of the ghosts of empire. The curriculum, such critics claim, is still too rooted in a colonial view of the world, too stuffed with European thinkers, and too blind to African, Asian and Latin American thinkers.

Neelam Chhara is a third year politics student at SOAS, and the Student Union officer for ‘Equality and Liberation’. ‘On my course in political theory’, she says, ‘we discussed 26 thinkers. Just two were non-European – Frantz Fanon and Gandhi.’ It was out of ‘frustrations with our curriculum’ that students set up the Decolonizing Our Minds group. ‘We thought: why not show what an alternative curriculum could look like by hosting thinkers and academics that didn’t centre Europe like our curriculum was doing.’

Meera Sabaratnam laughs when I tell her about Chhara’s reading list. ‘That’s two more non-Europeans than when I was taught political theory in my undergraduate PPE at Oxford.’ Sabaratnam is a lecturer in international relations at SOAS. As an institution, it is, she says, much better than most universities. For instance, 39 per cent of academic staff are of black or minority ethnic background – more than three times the figure for British universities overall. Nevertheless, Sabaratnam supports the Decolonizing Our Minds campaign. ‘It is necessary to talk about colonial legacies and to look at how colonialism and racism impact the institution.’

The argument for a more diverse curriculum seems reasonable, indeed unquestionable. After all, philosophers and thinkers come not just from Europe. There are great non-European intellectual traditions, a myriad philosophical schools from China, India, Africa and the Muslim world, many of which have shaped European philosophy. Three years ago, I wrote a book on the global history of ethics, called The Quest for a Moral Compass, which drew not just on European philosophers, but also on the works of Mo Tzu and Zhu Xi, Ibn Rushd and Ibn Sina, Anton Wilhelm Amo and Frantz Fanon, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Feng Youlan. All these different thinkers, I wanted to show, can be woven into a single but complex narrative through which we can rethink global history.

And yet, the debate about a ‘diverse curriculum’ is not as straightforward as one might imagine. Few would contest the idea that European thinkers should not be on the curriculum simply because they are European. But of the major European philosophers that often dominate reading lists – such as Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, Locke, Hobbes, Kant, Rousseau, Nietzsche, Arendt or Sartre – how many are there simply because they are European rather than because their ideas merit study?

Sabaratnam acknowledges the problem. ‘Framing a course is primarily about content: what are the issues that need to be taught, and who can speak interestingly about those issues? How many European thinkers you include and the balance between European and non-European thinkers is an academic decision. If you want to understand political theory, you can’t avoid engagement with Kant, Hegel and so on.’

‘But’, she adds, ‘that can’t be the be all and end all.’ There has, she insists, ‘to be a parallel debate about diversity and representation. There is value in having non-European thinkers and women on those reading lists.’

If European thinkers should not be on reading lists simply because they are European, should non-Europeans be included just because they are non-European, just for the value of increased diversity? Kwame Anthony Appiah, professor of philosophy and law at New York University, and last year’s Reith lecturer on Radio 4, is skeptical. He teaches a course on global ethics, which includes European, Chinese, Arab and Indian thinkers. The key question for him, however, is not ‘Is the curriculum sufficiently diverse?’ but ‘Is any particular thinker worth studying?’ ‘If they were uninteresting or unimportant’, he observes, ‘it would not be much of a defence to say “They are Arab or Chinese and make the course more diverse”.’

The difficulties in thinking about a diverse curriculum can be seen in the founding statement of the Decolonizing Our Minds campaign. It does not say ‘We need to expand our curriculum to include philosophers from across the globe’. Rather it insists (under the heading ‘Decolonising SOAS: Confronting the White Institution’) that, ‘If white philosophers are required, then to teach their work from a critical viewpoint.’ This suggests that not having white philosophers should be the default position. This might not quite be ‘students demanding white philosophers be dropped from university syllabus’, as the newspapers claimed, but it’s not that far off.

‘When you put it to me like that’, says Sian Hawthorne, ‘Yes, I think that is problematic. However, I take a more generous reading of that statement as saying whomever is taught, whosever’s work is drawn on, it must always be dealt with critically. That is one of the first principles of a university education.’

The students themselves told me that they had not realized what the statement actually said, and would change it.

Do we need to be particularly critical of white philosophers, I asked Hawthorne. Yes, she replied, because ‘whiteness has been engaged in perpetuating forms of oppression and marginalization and exclusion.’ Does she think that all European philosophy is tainted by racism and colonialism? ‘Yes. There’s plenty of evidence to demonstrate this.’

But in insisting that the work of all white philosophers from Aristotle to Arendt, from Socrates to Sartre, should be seen as tainted by racism, is she not confusing ideas and identity? Is she not falling into the same trap as racists, suggesting that because one possesses a particular identity, so one’s ideas are necessarily distinct, and linked to that identity? A philosopher is white so his or her ideas are contaminated.

Hawthorne rejects the criticism, and uses as an analogy the way that academics look upon the work of the German philosopher Martin Heidegger. Heidegger was one of the most influential twentieth century philosophers, having shaped the ideas of a host of thinkers such as Hannah Arendt, Jean-Paul Sartre and Jacques Derrida. He was also a Nazi with repulsively anti-Semitic views. The discovery of Heidegger’s Nazism and anti-Semitism has led to much debate about how to treat his philosophical ideas.

‘Do we deal with Heidegger because he was a Nazi?’, asks Hawthorne. ‘I think we must. But we must do so in the understanding that he was a Nazi. We don’t not read his texts. But we read them carefully. That should also be the case with white philosophers. Just because they’re white doesn’t mean that they’re written off. But we need to be careful.’

This, though, is a false analogy. What concerns many about Heidegger is not his skin colour or his identity but his political views. Asking whether Heidegger’s Nazi views should affect the way that we understand his philosophical ideas is different from insisting that because Aristotle or Kant or Arendt were white, so we should be careful in the way we read their writings.

‘Whiteness is not a useful category when talking of philosophy’, says Appiah. ‘When people speak, they speak ideas, not identity. The truth value of what you say is not indexed to your identity. If you’re making a bad argument, it’s a bad argument. It’s not bad because of the identity of the person making it.’

Perhaps the fiercest debate about European thought emerges in the battle over the Enlightenment, that sprawling intellectual, cultural, and social movement that spread through Europe during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and was the harbinger of intellectual modernity. There is no period of history that has been more analysed, celebrated and disparaged. Unlike, say, the Renaissance or the Reformation, the Enlightenment is not simply a historical moment but one through which debates about the contemporary world are played out. From the role of science to the war on terror, from free speech to racism, there are few contemporary debates that do not engage with the Enlightenment, or at least with what we imagine the Enlightenment to have been. Inevitably, then, what we imagine the Enlightenment to have been has become a historical battleground.

‘It’s become familiar to think of the Enlightenment as special’, Hawthorne suggests, ‘because it’s a constitutive narrative for how the West understands itself’. The Enlightenment, in her view, provides a myth, a creation story, that the West tells itself about what makes it more civilized and the rest of the world more barbaric.

Yet, for much of the past two centuries, the Enlightenment was seen as central to the values of the left, and of those challenging Western imperialism and injustice. As the late Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm put it, ‘All progressive, rationalist and humanist ideologies are implicit in it, and indeed come out of it.’

More recently, however, many on the left have argued that the Enlightenment, far from being a resource for those challenging colonialism, is itself a colonial project. Enlightenment universalism, such critics argue, is racist because it seeks to impose Western ideas of rationality and objectivity on other peoples. ‘The universalising discourses of modern Europe and the United States’, Edward Said argued in his book Culture and Imperialism, ‘assume the silence, willing or otherwise, of the non-European world.’ It is an argument central to the SOAS campaign.

SOAS academics and students argue that Enlightenment thinkers had a highly restricted notion of freedom; freedom as ‘the property of propertied white men’, as Meera Sabaratnam puts it. John Locke is widely regarded as having provided the philosophical foundations of modern liberal conceptions of tolerance. Yet he was a shareholder in a slaving company. Immanuel Kant, often seen as the greatest of Enlightenment philosophers, clung to a belief in a racial hierarchy, insisting that ‘Humanity is at its greatest perfection in the race of the whites’ and that ‘the African and the Hindu appear to be incapable of moral maturity’. ‘Enlightenment philosophers make arguments about knowledge and reason setting us free, and laud the values of liberty’, Hawthorne observes, ‘at the very moment that colonial enterprises and the slave trade are expanding. Those very same arguments are summoned to justify Europe’s so-called civilizing mission and make claims about European superiority.’

The British historian Jonathan Israel, now Professor Emeritus of History at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Princeton, is perhaps the most important contemporary scholar of the Enlightenment. Over the past decade, he has published an extraordinary trilogy of books, Radical Enlightenment, Enlightenment Contested and Democratic Enlightenment. The size of Israel’s labours is eye-catching. Each work in the trilogy runs to almost a thousand pages; in total there must be close to two million words here. There are few who better understand the Enlightenment.

Like many before him, Israel lauds the Enlightenment as that transformative period when Europe shifted from being a culture ‘based on a largely shared core of faith, tradition and authority’ to one in which ‘everything, no matter how fundamental or deeply rooted, was questioned in the light of philosophical reason’. Yet, Israel is also deeply critical. At the heart of his argument is the insistence that there were actually two Enlightenments. The mainstream Enlightenment of Locke, Voltaire, Kant and Hume is the one of which we know, and of which most historians have written. But it was the Radical Enlightenment, shaped by lesser-known figures such as d’Holbach, Diderot, Condorcet and, in particular, the Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza, that provided the Enlightenment’s heart and soul.

The two Enlightenments, Israel suggests, divided on the question of whether reason reigned supreme in human affairs, as the Radicals insisted, or whether reason had to be limited by faith and tradition – the view of the mainstream. The mainstream’s intellectual timidity constrained its critique of old social forms and beliefs. By contrast, the Radical Enlightenment ‘rejected all compromise with the past and sought to sweep away existing structures entirely’.

I talked to Israel about the SOAS debate. The argument that the ‘Enlightenment is racist’, he suggests, comes from a one-eyed view, the selective picking and choosing of certain individuals and quotes. Such critics see only the more conservative mainstream figures, such as Locke, Kant and Hume, and ignore the thinkers of the Radical Enlightenment, an approach that Israel calls ‘seriously obtuse’. The Radical Enlightenment, he observes, ‘was condemned by all European governments and by all churches, because in principle it insisted on the universal and equal rights of men and the full emancipation of the black population.’

In 1770 a remarkable polemic against colonialism and slavery called Histoire Philosophique des Deux Indes (‘The Philosophical History of the Two Indies’) was published. Written by a number of Radical thinkers including Raynal, Diderot and d’Holbach, it was both a study of Europe’s relations with the East Indies and the New World and an encyclopedia of anti-colonialism. Arguing that ‘natural liberty is the right which nature has given to everyone to dispose of himself according to his will’, the book both prophesied and defended the revolutionary overthrow of slavery: ‘The negroes only want a chief, sufficiently courageous to lead tem to vengeance and slaughter… Where is the new Spartacus?’

The Histoire was astonishingly successful, published in more than 50 editions in at least five languages over the next 30 years. But it was only one of many such radical tracts, including d’Holbach’s Systeme Sociale, Tom Paine’s Rights of Man, and the works of Condorcet and Diderot. ‘This current’, Israel argues, ‘was totally odds with all forms of imperialism, colonialism and racial discrimination or prejudice’. The Radical Enlightenment was ‘without question the starting-point for the anti-colonialism of our time’. In Israel’s view, what he calls the ‘package of basic values’ that defines modernity – toleration, personal freedom, democracy, racial equality, sexual emancipation and the universal right to knowledge – derives principally from the claims of the Radical Enlightenment.

Israel is sympathetic to the demand that university curricula be diversified. ‘There is a strong case for studying non-European traditions as an essential part of any philosophy teaching course.’ But, he points out, such a global view began in the Radical Enlightenment itself. ‘Many radical enlighteners believed their anti-Christian naturalism had powerful roots in medieval Islamic philosophy. They also had strong affinities with Chinese Confucianism. They were free of the Eurocentrism that marked the mainstream Enlightenment of Voltaire, Montesquieu, Hume and Smith.’

‘I wouldn’t want to go up against Jonathan Israel’, laughs Sian Hawthorne. ‘He is probably in the foremost thinker on the Enlightenment.’ ‘All I would say in response’, she adds, ‘is that there is no single thing that you can point to and say “That’s the Enlightenment”.’ That, however, is a view that fits more comfortably with Israel’s notions of the two Enlightenments, the mainstream and the Radical, than it does with the claim that ‘the Enlightenment is racist’.

Hawthorne is right, however, to point to Locke’s failure to challenge slavery and to Kant’s racial anthropology. Such views do seem shocking today. But they seem shocking because of the transformation in consciousness brought about in large part by the Enlightenment itself. In most societies and traditions, European and non-European, the kind of ethnocentrism expressed by many mainstream Enlightenment thinkers was the norm. The Enlightenment helped changed that. ‘I don’t know where you’d get the powerful tools for criticizing European colonialism if you did not have the Enlightenment’, observes Appiah. ‘The modern idea of equality, the modern critique of inequality – much of the materials for that idea and for that critique come from that period.’

One does not have to rely on historians like Jonathan Israel or philosophers like Anthony Appiah to make this point. It was made also by the very people who suffered under the yoke of European colonialism and sought to cast it off.

Today, most people know of the French and American Revolutions, two great social tumults whose reverberations we still feel. Few know of the other great revolution of the eighteenth century – the one in Haiti that began in 1791 and culminated with independence in 1804.

In 1791, a mass insurrection broke out among Haiti’s slaves, upon whose labour France had transformed Saint-Domingue, as it called its colony, into the richest island in the world. It was an insurrection that turned into a revolution, a revolution that defeated the three greatest armies of the age – the French, the British and the Spanish – to become the first successful slave revolt in history, a revolution that was to shape history almost as deeply as those of 1776 and 1789.

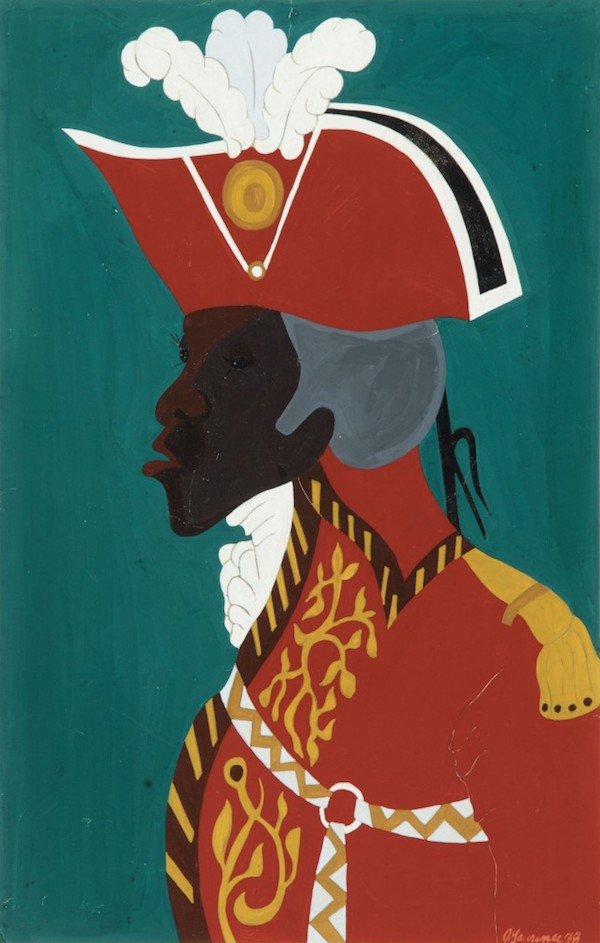

The slaves were led by Toussaint L’Ouverture, a self-educated former slave, deeply read, highly politicized and possessed of a genius in military tactics and strategy. He was the ‘Spartacus’ for which the European radicals who wrote the Histoire Philosophique des Deux Indes had pined.

Toussaint’s greatest gift, perhaps, was his ability to see that while Europe was responsible for the enslavement of blacks, nevertheless within European culture lay also the political and moral ideas with which to shatter the bonds of enslavement. The French bourgeoisie might have tried to deny the mass of humanity the ideals embodied in the Declaration of the Rights of Man. But Toussaint recognized in those ideals a weapon more powerful than any sword or musket or cannon.

From Toussaint L’Ouverture to Nelson Mandela, for two centuries those battling against European power and racial oppression looked to the Enlightenment ideals as the fuel for their struggles. Today, most of those struggles and movements have disappeared. As a result the meanings of ‘radicalism’ and ‘decolonization’ have withered, and come to mean something very different and much more tame than they did half a century or a century ago. Shorn of the social movements that gave Enlightenment values their radical edge, those values have lost much of their meaning. That today so many should so easily dismiss the Enlightenment in the name of ‘decolonization’ tells us more about the shaky foundations of contemporary radicalism than it does about the Enlightenment.

* * * *

The one word that Sian Hawthorne returns to again and again is ‘dialogue’. ‘We’re not used to see the world as the world. We keep cutting things up and segmenting them. Too often we don’t see the entanglements between European and non-European philosophies. What’s missing is dialogue.’

‘Dialogue’ is one of those words, like ‘diversity’, that can mean all things to all people. It is often used to define shallow, skating-on-the-surface conversations which give the impression of an exchange but which touch upon nothing substantive. It can also mean proper dig-deep contestations through which we test each other’s ideas and in which we show ourselves willing to be uncomfortable as we ourselves are tested. In both universities, and in society at large, there is today too little of the latter and too much of the former; too little real engagement and too great a desire to stay within our comfort zones.

There is much on which I disagree with the ‘Decolonizing Our Minds’ approach. I disagree with its concept of ‘whiteness’, with the characterization of the Enlightenment as ‘racist’, with the understanding of what ‘European thought’ constitutes, with what it means to ‘decolonize’. What I admire, though, is their openness to have this debate, and to engage in the kinds of conversations I had with both students and academics. I spent an afternoon discussing, debating and disagreeing with Meera Sabaratnam. At the end she said, ‘The discussion that we’re having now is exactly the kind of discussion that it should be possible to have at universities.’ On that, I could not agree more.

The images are, from top down: Raphael’s ‘The School of Athens’; Frantz Fanon; Immanuel Kant (painter unknown); Hannah Arendt (photo by Fred Stein); John Locke, portrait by Godfrey Kneller; Jonathan Israel (my photo); and Tousaint L’Ouverture by Jacob Lawrence.

Hi Kenan, thanks -really enjoyed this. I’ve not read the Jonathan Israel history trilogy, but nonetheless wonder whether two Enlightenments thesis is best way of understanding it – would there not have been important areas of overlap?

Yes, there are important overlaps. The intellectual and political divide between the Radicals and the mainstream was not as sharp as Israel suggests. Hobbes was an atheist and a materialist but a political authoritarian. Hume was an atheist but politically and socially conservative. Rousseau and Kant were theists but supportive of revolutionary thinking. Many revolutionaries, such as Tom Paine, rejected institutionalized religion but accepted a Deistic idea of God. Nevertheless, however fuzzy the boundaries may be, the distinction between the Radical and the mainstream Enlightenment, is, in my view, important and illuminating, and provides a powerful framework through which to understand intellectual and social conflict both in the Enlightenment and the post-Enlightenment worlds. Israel’s work is of immense importance, and allows us to rethink the Enlightenment in a fruitful way. I did, by the way, a long interview with Israel where we discussed some of our other differences (including on the historical roots of the radical Enlightenment).

Sorry, had originally put in the wrong link. It’s corrected now.

Hi Kenan, interesting article as always. I wonder if one could add a consideration of what is meant by “approaching from a critical viewpoint”. My experience is that in practice, when this is said, the common assumption is that “critical” means “using critical theory” i.e. a specific philosophical nexus that draws on post-structuralism. The major problem with that approach is that as it is practiced, it often ends up in circular defences and sort of dog-in-the-manger approach: ‘only we are critical’. This was tackled in a thoughtful book, “The limits of critique” by Rita Felski (Chicago UP, 2015)

I agree about problems with ‘critical theory’. I suppose my view is: why should critical theorists be the only ones who define what it means to be critical?

Yes precisely! An old argument which never seems to die. Felski tries to shift it to a new frame.

Wonderful post, thank you.

I used a quote from Israel to open my bibliography for Pan-Africanism, Black Internationalism, & Black Cosmopolitanism:

‘We are trying to save millions of men from ignominy and death,’ wrote Condorcet in 1788, in a text condemning the slave trade, ‘to enlighten those in power about their true interests and restore to a whole section of the world the sacred rights given to them by nature.’ The advent of black liberation in the Caribbean during the years 1788-94 confirms that la philosophie modern was not only the primary shaping impulse of the French Revolution but the primary spur to black emancipation in the late eighteenth-century Caribbean world. The social revolution that ensued during the years 1792-97 was not merely concerned with abolishing slavery as such, like the Christian abolitionist movements in England and Pennsylvania, but formed a broader, more comprehensive emancipation movement seeking to integrate the entire black population—‘free blacks’ and slaves—into society, legally, economically, educationally, and also politically.—The opening paragraph of the chapter on “Black Emancipation” in Jonathan Israel’s Revolutionary Ideas: An Intellectual History of the French Revolution from The Rights of Man to Robespierre (Princeton University Press, 2014): 396.

Thanks.

Very informative piece. Thanks.

The dichotomy between prejudiced reasoning vs critical reasoning came to mind in relation to the Decolonising Project.

I definitely get the interesting separation you are making between political opinion and identity but

1) what is your definition of identity.

2) when political views are expressed, then it is rare that the opinion is expressed from an identity-neutral perspective.

E.g the SOAS students are expressing a specific political view that white (mainstream) enlightenment philosophers have double standards regarding their ethics which renders their morality as racist which is clearly ‘inter-related’ to their own identity-conceptions of being subject to political-economic imperialism. In other words, the juxtaposition of racial/ethnic identities in this situation with one set feeling underprivileged in relation to the other is seeking to express their discontent through a prejudiced narrative. Although there are racist undertones to this narrative, it is better to dialogue with the argument rather than the identity expressing that prejudism, thereby practicing the radical enlightenment ideals of toleration, personal freedom, democracy, racial equality, sexual emancipation and the universal right to knowledge.

In this respect the political view and the ‘inter-related’ identity expressing that view are co-joined but in order to realise the radical enlightenment ideals, it is prudent to engage with the argument rather than the identity.

Lastly Id argue that the radical enlightenment ideals are essentially human-centric and consequently specist in their outcomes due to the high demand in resources that are required to create the civil and civic institutions and infrastructure to facilitate this human-centric form of natural justice.

Hence the modern age precipitated by the age of enlightenment is nearing completion as we begin to journey into the ecological age whereby natural justice will need to be extended to all life-forms.

If you are going to extend “natural justice” to all life-forms, you will – as a a first step – have drastically to reduce the number of human beings, so as to give room and resources to other species.

How do you propose to bring about this reduction in human numbers ? Or should I not enquire too closely ?

And do you, as your remarks about the Enlightenment being speciesist suggest, believe we should return to a radically simpler, pre-industrial way of life (naturally without IT or modern medicine, of course) ? You lead the way, if so !

Finally, there is. of course, no such thing as “natural justice.” Nature is nothing if not unjust.

Some mammals are peeved if unjustly treated. Nevertheless, the abstract idea of Justice is a by-product of the human mind and therefore, speciesist.

Do you not have any possible solutions to your quandries yourself especially as you believe radical enlightenment is a figment of man’s imagination rather than say a signifer of human evolution then I guess we are looking at a war against all.

However since I believe the radical enlightenment is an evolutionary moment for humanity I’ll proceed.

Enlightenment ideals if manifested will ultimately produce the reasoned argument that human rights fulfillment will reach ecological limits especially if ecosystem service provision and wildlife habitats are to be preserved for human health and well-being.

As such, ecological limits will create an emphasis on social justice which of course is the human dimension of natural justice.

In order to enable natural justice for non-human communities then human impacts can be differentiated between low, medium and high with an emphasis on ensuring available resource use is within scientifically defined limits and then shared equitably to different human communities depending on need.

Rate of human population growth is due to end by 2050 so from there on human populations will stabilise. If human needs can be satisfied by this time then perhaps we can think collectively about managed population decreases through family planning.

Ultimately one would hope that the radical enlightenment ideals of toleration, personal freedom, democracy, racial equality, sexual emancipation and the universal right to knowledge would extend as best as possible to the non-human community and perhaps most importantly of all, for the ideals to create a species collective consciousness that can then form the platform for human collaborative effort to ensure human impact is within ecological limits.

Thanks for reply Kenan – will read your interview and, one day soon, read at least some of Israel!

At a conference on the history of technology last year, a special panel on the Philippines was convened. Predictably, the only people in the room seemed to be Filipinos or Philippines specialists. The historians who literally work on rocket science basically had a completely different conference from ‘the rest of us’. The equivalents of rocket science in the humanistic studies – Plato in philosophy, American history in political history – dominate by custom and sheer force of cumulative impact. A fresh start, or alternative start, or merely doing more work along non-traditional lines – these seem to be what’s needed.

We may well applaud the ideas that inspired the French and Haitian Revolutions.

It would, however, be wrong of us to applaud those revolutions as political events, since both were bloodbaths. And bloodbaths, moreover, from which no good has come either to France or to Haiti. (The UK – which didn’t have a radical revolution – is in most ways a better, more influential country than France, which did).

As regarding fair play for the non-Western world, Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand, working through globalised capitalism, seems to have achieved far more, especially since the 1980’s, than any liberal or radical ideas.

The West is at present undergoing the first real Sea Change it has undergone since c.1450, when it stumbled from the Middle Ages into Modernity.

And this is happening at a speedy, alarming pace. The near-collapse of the West (especially the USA) since the Millennium has been rather frightening.

No wonder populists, no wonder newspaper editors choking over their coffees about the SOAS debate.

Apologies Kenan. Had I realised that you had a website that “thrives on debate” and welcome people with “do join in” I wouldn’t have bombarded you with so many tweets and would have posted my comments here instead. If you don’t feel able to address any of my points on Twitter, perhaps you could reply here instead? It would be very much appreciated.

And in Boston, yesterday, in fact on the very day this article was published, hundreds of scientists and their supporters held a rally to defend the very idea of evidence-based thinking against the forces that now want to overturn it. Honestly, someone like Donald Trump is making the Enlightenment seem better and better everyday.

Hi Kenan, thanks very much for this engaging article. I have very much enjoyed reading it. It’s great to get this discussion going. I teach one of the courses (at SOAS) under analysis in this debate. A few years ago I transformed the syllabus to include more women and people of colour. My intention has been to diversify the curriculum and teach it conceptually (rather than historically) to give various perspectives on core concepts in political theory. Last year, I wrote a blog about how I have changed the course : https://psawomenpolitics.com/2015/12/21/on-teaching-political-theory-to-undergraduates/. Of course, this does not mean that the historical context should be disregarded since how we understand this influences how we read particular texts; for instance, looking at the Enlightenment through the lens of colonial empire and the slave-trade serves to highlight radical from conservative thinking. It is great we can do this rather than study thinkers through the narrative of a particular and often historical canon.

Why is there not a more extensive critique of the “MALE” centric-ness of curricula?

This is very much to the point. To me, diversifying the curriculum is not simply about race and culture, but also it is about gender. The canon of great minds tends to be dominated by men, notably from Europe and North America. Not only are women and people of colour excluded from this canon, but also many great thinkers considered women and people of colour less rational than men and excluded them from political institutions and processes. I take the project of ‘decolonizing the mind’ to mean recognition of these exclusions and prejudices and critical engagement with these philosophers (without necessarily invoking critical theory in the use of the term critical). Once we recognize this, then we can diversify the curriculum and consider thinkers of different times, spaces and perspectives together in a syllabus that instructs in political theory writ large. Frequently universities teach feminism and post-colonialism as areas of thought apart from political theory, but to do this is to reinforce separate ‘bodies of knowledge’ and exclusions. Crucially, to do this is to miss the dialogue that occurred across these boundaries, such as the rich conversations that Thoreau had with ancient Indian philosophy and Gandhi with Thoreau, or Mary Astell with Hobbes and Locke.