This is a transcript of a talk I gave at the Kreisky Forum in Vienna on 11 May 2017. It pulls together many of the themes from previous talks and essays.

Last week a 20-year-old Briton called Damon Smith was found guilty of planting a homemade bomb filled with ball bearings on a London Underground train. Police discovered in his flat shredded pages of an article titled ‘Make a bomb in the kitchen of your mom’ from Inspire, a magazine published by an al-Qaida affiliate. They also found on his iPad a shopping list for ‘pressure cooker bomb materials’. The note included a reminder to ‘keep this a secret between me and Allah’ and finished with the hashtag #InspireTheBelievers’. On his computer were photos of Alan Henning,the aid worker beheaded by IS, as well photos of the ringleaders of the 2015 Paris attacks.

And yet there was nothing to connect Smith to any extremist network. He was relatively ignorant of Islam, and had never even been inside a mosque, part from once on holiday in Turkey. He suffered from Asberger’s syndrome. He had been bullied at school, and suffered from other behavioural issues. At Smith’s trial the judge asked the jury to disregard his strange behaviours, such as smiling while listening to the prosecution case against him. Smith, the judge observed, was ‘acutely aware that he’s presenting himself in a manner that is odd and unsympathetic’.

Was Damon Smith a jihadi? Not in any conventional sense of the word. And yet, he inhabited what we might call a ‘jihadi frame of mind’, to the extent that he planted a bomb on a train, even if he insisted that he did it as a ‘prank’. Bombs were ‘something to do when he was bored’, he told a psychiatrist

Damon Smith may seem an odd, strange figure, whose oddness and strangeness means that he can tells us little about contemporary jihadism. Little about the fighters who really go to Syria, to behead and blow up people, who would never dream of excusing their actions as a ‘prank’. Smith is certainly very different from Jihadi John, the British jihadist who became infamous for taking part in mass beheadings in Syria which were videoed and broadcast on the Internet, or the Kouachi brothers who were responsible for the murderous assault on the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris. But in many ways, Smith’s story highlights the character of contemporary jihadism as much as theirs do. For what exactly it is to be jihadist is these days much more difficult to discern.

Over the past forty years the character of jihadism has changed considerably. There have been at least five iterations. The first wave of jiahdis comprised the mujahedeen fighting Soviet forces in Afghanistan. The second wave was made up largely of elite expatriates from the Middle East who went to the West to attend universities, and then to fight in hotspots such as Bosnia, Chechnya, and Kashmir. A third wave, the first wave of European ‘homegrown jihadis’, emerged in the wake of the Iraq War of 2003. By 2010 this third wave had run its course. But the Syrian civil war, and the emergence of Islamic State in particular, gave rise to a new, wave of wannabe foreign fighters. According to Rik Coolsaet, Professor of International Relations at Ghent University, this fourth wave consists of two elements. Firstly gang members, for whom ‘joining IS is merely a shift to another form of deviant behaviour’. And, second, are what Coolsaet calls ‘solitary, isolated adolescents, frequently at odds with family and friends, in search of belonging and a cause to embrace, who previously showed no sign of deviant behaviour’.

And now, as IS disintegrates, we have the rise of ‘low tech’ terrorism – perpetrators causing terror through the use, not of bombs and AK 47s, but of everyday objects – knives and cars. From the horrific truck attack on Bastille Day revellers in Nice last year, to the car driven into a Christmas market in Berlin, to the attack on Westminster Bridge, in London, in March, to the car driven into a department store in Stockholm, the mowing down pedestrians with vehicles has turned into the weapon of choice for low tech terrorists.

Knife attacks, too, are becoming a common feature of low-tech terrorism, from the beheading of the soldier Lee Rigby beheading on the streets of south London in 2013 by Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale, to the wounding in 2015 of three people in Leytonstone tube station in east London when 29-year-old Muhaydin Mire, ran amok with a knife, apparently as some form of deluded response to the war in Syria, to the murder last year of a priest, Father Jacques Hamel, in a church in Saint Etienne-du-Rouvray, in northern France, by two teenage Islamists, Adel Kermiche and Abdel Malik Petitjean.

The proliferation of these low-tech attacks exposes the continuing degeneration of Islamist terror. It exposes, too, the increasingly blurred lines between ideological violence and sociopathic rage. Last August, Zakaria Bulhan, a 19-year-old Norwegian of Somali descent, went on a rampage in Russell Square in London, stabbing six people, one of whom died from her injuries. It was originally seen as a terrorist incident. Later, Bulhan was diagnosed as suffering from paranoid schizophrenia. Last month, a court ordered him to be detained indefinitely in Broadmoor maximum security hospital.

A week before Bulhan’s rampage, a 21-year-old Syrian refugee had hacked a woman to death in Reutlingen, near Stuttgart in Germany. That, too, was first regarded as a terrorist incident, only later as the actions of a mentally disturbed man. In both cases, many refused to believe that these were not terrorist incidents and social media spawned dark conspiracy theories of official cover-ups. Such theories may be irrational, but they reflect, too, the difficulty, often, in drawing a distinction between jihadi violence and the fury of disturbed minds.

The degeneration of jihadism, and the blurring of lines between terror and rage, exposes more clearly the character of jihadism. Both jihadis, and many in the West, have long claimed that these acts of terror were political responses to Western foreign policy and to Islamophobia at home. Western intervention in the Middle East and in Muslim-majority countries elsewhere, many Western critics suggest, from the war in Iraq to the support for Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, has radicalized many Muslims and pushed them into the hands of the jihadis.

I am deeply critical of many aspects of the foreign policies of Western powers. But the argument that Western policy explain jihadi violence makes little sense. Western governments were intervening in Muslim-majority countries long before Osama bin Laden took to a cave in Afghanistan, let alone the Islamic State began its brutal rule in swathes of Iraq and Syria. From Winston Churchill ordering the use of mustard gas against Iraqi rebels in the 1920s, to the CIA engineering a coup against the democratically elected government of Mohammed Mossadeq in Iran in 1953, to the brutal attempt by the French to suppress the Algerian independence movement in late 1950s, to Western backing for Saddam Hussein in his war against Iran in the 1980s – there is a long history of such intervention. There is also a long history of resistance, often violent resistance, to such intervention, and often violent resistance. But specifically Islamic opposition is relatively new, and nihilistic terrorism newer still.

And it is the nihilism, and the arbitrariness, not any political mission, that defines contemporary Islamist terror and makes contemporary jihadism different from previous terror campaigns. The rise of low-tech terrorism makes that nihilism much more apparent, and makes it more difficult to see such acts as political responses to Western policy (though some still try).

In the past, groups employing terror, whether the IRA or the PLO, were driven by specific political aims – a united Ireland or an independent Palestine. They had exclusive memberships; not anyone, for instance, could become an IRA volunteer; you had to be chosen for your skills beliefs and attitudes. There was generally a close relationship between the organisation’s political cause and its violent activities. And, whatever one thinks of such groups, those activities were governed by certain norms and contained a rational kernel.

Jihadis, on the other hand, have no explicit political aim, no defined membership, no leadership exercising control. An act of terror is not related to a political demand. It is simply an act designed to terrorize for the sake of causing terror. Many civilians were certainly killed through IRA violence, but, unlike jihadis, the starting point of the IRA was not the mere killing of random individuals. As the French sociologist Olivier Roy puts it, ‘the nihilist dimension is central’ to ‘today’s radicalization’. ‘What seduces and fascinates’, he argues ‘is the idea of pure revolt. Violence is not a means. It is an end in itself.’

Of course, in the mind of the perpetrators, there is always a relationship between Western policy and their acts of terror. They imagine themselves as waging a righteous war against the West. But the West, in their minds, is not a set of specific nations responsible for specific acts, but an almost mythical, all-encompassing monster, the source of all manner of horror and dread. That is why a jihadist act is rarely linked to a political demand but is seen rather as an existential struggle to cut the monster down, a struggle in which almost any act becomes acceptable.

Islamic State has claimed responsibility for many low-tech terror attacks, including the attacks in Nice, Berlin and Westminster. In each case it called the perpetrators its ‘soldiers’. Whether any of the attackers had real links to IS remains unclear. ‘Soldiers of the Islamic State’ are often just unstable young men with only the most tenuous relationship to IS but driven by a sense of inchoate, personal rage, individuals lacking direction, and finding in Salafism a sense of order and meaning, and of making sense of their inner furies.

All this challenges the common notion of ‘radicalization’, an idea that has caught the imagination of politicians, policy makers and the public. Much of domestic counter-terror policy in Europe is rooted in notions of radicalization and de-radicalization. But as a means of explaining why Europeans get drawn into jihadism it is not particularly useful concept.

The concept of radicalization is built out of four basic elements. First, the claim that people become terrorists because they acquire certain, usually religiously informed, extremist ideas. Second, that these ideas are acquired in a different way to the way people acquire other extremist or oppositional ideas, such as , say, Marxism or anarchism, or mainstream ideas such as conservatism or liberalism. Third, that there is a ‘conveyor belt’ that leads from grievance or personal crisis to religiosity to the adoption of radical beliefs to terrorism. And, fourth, the insistence that what makes people vulnerable to acquiring such ideas is that they are poorly integrated into society.

There is, however, little evidence in support of any of these four elements of radicalization, and considerable evidence to suggest that all are untrue. Many studies show, for instance, perhaps surprisingly and counter-intuitively, that those who are drawn to jihadi groups are not necessarily attracted by fundamentalist religious ideas. According to a British MI5 ‘Briefing Note’ entitled ‘Understanding radicalisation and extremism in the UK’, and leaked to the Guardian,

Far from being religious zealots, a large number of those involved in terrorism do not practise their faith regularly. Very few have been brought up in strongly religious households, and there is a higher than average proportion of converts.

Marc Sageman, a former CIA operation officer with the Afghan mujahidin in the late 1980s, and now an academic and counter-terrorism consultant to the US and other governments, similarly finds that ‘a lack of religious literacy and education appears to be a common feature among those that are drawn to [terrorist] groups.’ ‘At the time they joined jihad’, Sageman observes, ‘terrorists were not very religious. They only became religious once they joined the jihad.’

There is also little evidence that jihadists acquire their ideas differently from the way people may acquire other kinds of ideas. According Jamie Bartlett, head of the ‘Violence and Extremism program’ at the British think tank Demos, ‘al-Qaeda inspired terrorism in the West shares much in common with other counter-cultural, subversive groups of predominantly angry young men’.

Nor is there any evidence of a conveyer belt leading people from radical ideas to jihadist violence. Even most studies funded by government agencies or the security services disavow such an idea. One US Department of Homeland Security-sponsored academic study, concludes that

There is no one path… to political radicalization. Rather there are many different paths… Some of these paths do not include radical ideas or activism on the way to radical action, so the radicalization progression cannot be understood as an invariable set of steps or “stages” from sympathy to radicalism.

A 2010 British government report similarly concluded,

We do not believe that it is accurate to regard radicalization in this country as a linear “conveyor belt” moving from grievance, through radicalization, to violence … This thesis seems to both misread the radicalization process and to give undue weight to ideological factors.

And finally, there is much evidence that those who join jihadi groups are anything but poorly integrated, at least in the conventional sense of looking at integration. A survey of British jihadis by researchers at Queen Mary College in London found that support for jihadism is unrelated to ‘social inequalities or poor education’; rather, those drawn to jihadist groups were 18- to 20-year-olds from wealthy families who spoke English at home and were educated to a high, often university, level. Or, as the study sardonically out it, ‘Youth, wealth, and being in education… were risk factors’. Insofar as they are alienated, it is not because wannabe jihadis are poorly integrated, in the conventional way we think of integration, or because they because they are poor or lack resources.

Today, as I have suggested, European jihadis are more likely to be gang members than professionals. But gang members are no less integrated. They are deeply immersed in youth culture. Far from the image of austere, religious-defined Muslims separated from society, what is striking about such would be jihadis is that their life is defined by drinking, clubbing, drugs and petty crime. In their dress style or music tastes they are fully part of contemporary youth culture. As Rik Coolsaet puts it, they see jihadism as merely a continuation of their gang life, ‘a shift to another form of deviant behaviour, next to membership of street gangs, rioting, drug trafficking and juvenile delinquency.’ But, Coolsaet observes, ‘it adds a thrilling, larger-than-life dimension to their way of life – transforming them from delinquents without a future into mujahedeen with a cause.’

The problem with the conventional radicalization thesis is that it looks at the issue the wrong way round. It begins with jihadists as they are at the end of their journey – enraged about the West, with a back and white view of Islam, and a distorted moral vision – and assumes that these are the reasons that they have come to be as they are. That is rarely the case. Few jihadists start off as religious fanatics or as political militants. That is why their journey to Syria, or their involvement in an act of terror, often comes as such a shock to family and friends.

Radical Islam, and a hatred of West, is not necessarily what draws individuals into jihadism. It is what comes to define and justify that jihadism.

So if not religion or politics, what is it? ‘The path to radicalization’, as the British academic Tufyal Choudhury put it in his 2007 report on The Role of Muslim Identity Politics in Radicalization, ‘often involves a search for identity at a moment of crisis… when previous explanations and belief systems are found to be inadequate in explaining an individual’s experience.’

Jihadis, in other words, begin their journey searching for something a lot less definable: identity, meaning, respect. The starting point for the making of a homegrown jihadi is not so much ‘radicalization’ as social disengagement, a sense of estrangement from, resentment of, Western society. It is because they have already rejected mainstream culture, ideas and norms that some Muslims search for an alternative vision of the world.

It is not surprising that many wannabe jihadis are either converts to Islam, or Muslims who discovered their faith only relatively late. In both cases, disenchantment with what else is on offer has led them to the black and white moral code that is Islamism. It is not, in other words, simply a question of being ‘groomed’ or ‘indoctrinated’ but of losing faith in mainstream moral frameworks and searching for an alternative. As Rik Coolsaet observes of what he calls the isolated indiviuals who become jihadis, they ‘showed no sign of deviant behaviour and nothing seemed to distinguish them from their peers’, before they suddenly turned to jihadi terror. But, he adds,

frequently they refer to the absence of a future, to personal difficulties they faced in their everyday life, to feelings of exclusion and an absence of belonging, as if they didn’t have a stake in society. They are often solitary, isolated adolescents, frequently at odds with family and friends, in search of belonging and a cause to embrace. At a certain point, the accumulation of such estrangements resulted in anger.

Disengagement is, of course, not simply a Muslim issue. There is today widespread disenchantment with the political process, a sense of being politically voiceless, a despair that neither mainstream political parties nor social institutions seem to comprehend their concerns and needs, a rejection of conventional ideals and norms that seem detached from their experiences.

All this has inevitably shaped how young people, and not just of Muslim backgrounds, experience their alienation, and how they are able to act upon it. It is necessary, therefore, to understand both what connects Muslim and non-Muslim disaffection, and what distinguishes them.

In the past, disaffection with the mainstream may have led people to join movements for political change, from far-left groups to labour movement organizations to anti-racist campaigns. Such organizations helped both give idealism and social grievance a political form, and a mechanism for turning disaffection into the fuel of social change. Today, such campaigns and organizations often seem as out of touch as mainstream institutions. What gives shape to contemporary disaffection is not progressive politics, as it may have in the past, but the politics of identity. Identity politics has, over the past three decades, encouraged people to define themselves in increasingly narrow ethnic or cultural terms.

Partly because of these changes, the notion of what it is to be Muslim has also changed. There is much talk of the ‘Muslim community’, of its views, its needs, its aspirations. But the ‘Muslim community’ is a recently-constructed concept. Until the late 1980s, few Muslim immigrants to Europe thought of themselves as belonging to any such thing as a ‘Muslim community’. One of the problems in much of the discussion of radicalization is, in my view, the lack of a historical perspective.

The first generation of North Africans to France were broadly secular, as were the first generation of Turkish migrants to Germany. The first generation of postwar Muslim immigrants to Britain, largely from the Indian subcontinent, was certainly religious, but wore its faith lightly. Many men drank alcohol. Few women wore a hijab. Most visited the mosque only occasionally, when the ‘Friday feeling’ took them. Faith was not, for them, a public identity. They may have thought of themselves as Punjabis or Bengalis or Sylhettis but rarely as ‘Muslims’.

The second generation, in Britain as well as in continental Europe, was primarily secular. It is only with the generation that has come of age since the late 1980s, that the question of cultural and religious differences has come to be seen as important. A generation that, ironically, is, from one perspective, more integrated and ‘Westernised’ than the first generation, is also the generation that is most insistent on maintaining its ‘difference’.

The reasons for this shift are complex. Partly they lie in the tangled set of social, political and economic changes over the past half century, changes that include the retreat of the left, the demise of class politics, the rise of identity politics, the narrowing of the political sphere, the erosion of more universalist visions of social change. Partly they lie in international developments, from the Iranian revolution of 1979 to the Bosnian war of the early 1990s, that played an important role in fostering a more heightened sense of Muslim identity in Europe.

And partly they lie also in the development of public policies, both of multicultural policies, in a country like Britain, and assimilationist policies in France. From very different starting points, both kinds of policies have come to foster more fragmented societies and narrower visions of social identity. Both the multicultural notion of a nation as a ‘community of communities’ and the assimilationist approach of looking upon Islam as the ‘Other’ against which French national identity is established, have helped entrench the politics of identity and to accentuate the sense of ‘difference’ that has shaped social relations over the past three decades.

In the past, most Muslims, in Britain or in France, would have regarded their faith as simply one strand in a complex tapestry of self-identity. Many, perhaps most, Muslims still do. But there is a growing number that see themselves as Muslims in an almost tribal sense, for whom the richness of the tapestry of self has given way to an all-encompassing monochrome cloak of faith. Yet, most wannabe jihadis are often as estranged from Muslim communities as they are from wider Western society. Most detest the mores and traditions of their parents, have little time for mainstream forms of Islam, and cut themselves off from traditional community institutions. Disengaged from both Western societies and Muslim communities, some reach out to Islamism.

What Islamism provides is not religion in any old-fashioned sense, but identity, recognition and meaning. Detached from traditional religious institutions and cultures, many adopt a literal reading of the Qur’an and a strict observance of supposedly authentic religious norms to mark themselves out as distinct and provide a collective identity.

At the same time, Islam as a global religion allows Islamist identity to be both intensely parochial and seemingly universal, linking Muslims to struggles across the world, from Afghanistan to Chechnya to Palestine, and providing the illusion of being part of a global movement. Islamism provides also the illusion of a struggle for a better world. And in an age in which traditional anti-imperialist movements have faded, and belief in an alternative to capitalism dissolved, Islamism seems to provide the possibility of both an alternative to capitalist society and of a struggle against an immoral system.

Disembedded from social norms, finding their identity within a small group, shaped by black and white ideas and values, driven by a sense that they must act on behalf of all Muslims and in opposition to all enemies of Islam, it becomes easier to commit acts of horror and to view such acts as part of an existential struggle between Islam and the West.

Where does low tech terrorism fit into this? What the emergence of Islamist terror, and of European jihadism in particular, reveals is the consequence of inchoate rage without a political outlet, but shaped by a sectarian, nihilistic, misanthropic, religious outlook. Over the past three decades the political pretensions of jihadism have increasingly been stripped away. The logical end-point of this process is the meaningless, random low tech terrorism where the line between the ‘political’ and the ‘mentally disturbed’ is impossible to discern.

Deranged fury cloaked in ideological rage is not uniquely Islamist. Two days before the recent attack in London, when Khalid Masood mowed down pedestrians on Westminster Bridge before killing a policeman with a knife, James Harris Jackson allegedly stabbed to death Timothy Caughman in Manhattan. Jackson was white, Caughman black. Jackson is said to have come to New York from Baltimore armed with a knife and a sword and with the aim of killing as many black people as possible. ‘I hate blacks’, he told police. He chose to make New York the scene of his murderous act because it was ‘the media capital of the world’ and he ‘wanted to make a statement’. The police are uncertain whether Jackson had any formal links to racist groups. But, as with many Islamist killings, this stabbing blurs the line between ideological violence and psychotic rage. At his arraignment, the prosecutor called it ‘an act, most likely, of terrorism’. Defence counsel talked of Jackson’s ‘obvious psychological issues’.

This murderous act is not an isolated incident. In 2015, Dylann Roof, a 21-year-old American obsessed with white supremacist ideas, shot dead nine African American worshippers in a church in Charleston, South Carolina. Last July, Ali David Sonboly went on a rampage in a Munich shopping mall, shooting dead nine people, and injuring another 36. He was of Iranian origin, and so the attacks was initially reported as an act of Islamist terror. But being Iranian meant to Sonboly not ‘Muslim’, but ‘Aryan’. He was obsessed by mass shootings and lauded Anders Behring Breivik, the Norwegian neo-Nazi who killed 77 people in Oslo and Utøya in 2011, and proud of sharing his birthday with Adolf Hitler. A month earlier, in Britain, Thomas Mair, a 53-year-old man with links to far-right groups, had shot and stabbed to death Jo Cox, a Labour MP, while she was campaigning in the EU referendum, in Birstall, Yorkshire.

All this exposes both how the character of ideological violence has degenerated and how rage has become a feature of public life. The social and moral boundaries that act as firewalls against such behaviour have weakened. Western societies have become socially atomised. The influence of institutions that once helped socialise individuals and inculcate them with a sense of obligation to others, from the church to trade unions, has declined. So has that of progressive movements that gave social grievance a political form. All this has spawned a proliferation of angry, unbalanced individuals, detached from wider society and its norms, denied political outlets for their disaffections and who find in Islamism or white nationalism the balm for their demons and the justification for their actions.

Against this background, most of the policy responses to jihadism have have attempted to tackle the wrong problems, and so have helped to create more illiberal societies without challenging jihadism. There are broadly four kinds of policy approaches to the problem of contemporary terrorism. The first sees jihadis as a problem external to Europe and so looks to tough immigration controls, particularly for Muslim migrants, to stem jihadism. The problem of jihadism, the argument goes, is a problem of migration, because it is the arrival into Europe of those with fundamentally different values and beliefs, and with a hatred European civilization, that lies at the root the European jihadist problem. Close off the borders, stop the influx of Muslims, and Europe will begin to be able to deal with the issue of jihadism within.

The trouble is, the problem is not out there but in here. Homegrown jihadis are homegrown – born in Europe. Controls on immigrations would do little to prevent Europeans from being drawn towards jihadism.

The second approach focuses on mosques and preachers – increasing surveillance, jailing ‘hate preachers’, insisting that imams preach in the local language, rather than Arabic, and so on. The trouble is, European jihadis are rarely radicalized through mosques. They find ideas and identities in friendship groups, through social media, on the internet. The counter-terror obsession with mosques and preachers is like putting a roadblock on the motorway, when the quarry has already slipped away through the side roads.

Third, there are restrictions on organizations and speech that promote extremist ideas or hate. Again such measures do little to deny jihadis access to their poison, but betray rather they the liberties that the ‘war on terror’ supposedly helps defend, while also entrenching forms of hypocrisy that help deepen the sense of alienation and disengagement that has made Islamism attractive to some in the first place.

And finally, there are policies aimed at greater integration. Integration is, of course, an important issue in itself. But, when it comes to jihadism, the problem, as we have seen, isn’t a lack of integration. It is rather the fragmentation of society, the weakening of moral boundaries, and attractions of terrorism as a form of revolt in itself. The irony is that many of the policies aimed at furthering integration, whether such policies are multicultural or assimilationist, has resulted in more fragmented societies, narrower visions of belongingness and identity, and deeper divisions between social groups.

The stark reality is that there are no easy, off-the-shelf solutions. The challenge we face is not just confronting jihadism in the narrow sense – disrupting the networks, preventing individual acts of terror – but also tackling in a broader sense what I have called ‘the jihadi state of mind’: that melange of social disengagement, moral dissolution, unleavened misanthropy and nihilistic rage that underlies the contemporary attraction of violence and terror as a form of revolt to some in the West.

It is a state of mind that finds its most vicious, barbaric form in Islamist terror. But, as I have suggested, it is not only in Islamist terror that it finds expression. Tackling this deeper problem requires us to tackle not just the commission of acts of terror, but a host of deeper issues – the atomization of society, the rise of identity politics and the narrowing of people’s sense attachments and belonging, the crumbling of the institutions of civil society, the disappearance of organizations that helped give social grievance a political form. Tacking such issues are certainly not as politically sexy as demanding ‘Close the borders’, ‘Stop the Muslims’ or ‘Shut down that mosque’. But they do take us beyond the superficial and the counterproductive.

Finally, we need to maintain a sense of perspective. Low tech terror reveals how easy it is cause mayhem and disruption in an open, urban, society. That is why such attacks are so terrifying. But they should also remind us that, given how easy it is to sow terror, these kinds of attacks are relatively infrequent. Most people have access to cars and knives. The fact that such attacks are, nevertheless, so rare – and, hence, so shocking when they do occur – tells us something powerful about the enduring strength of social bonds. The aim of terrorists is to erode those bonds. Whether they succeed will depend less on the terror than on our response.

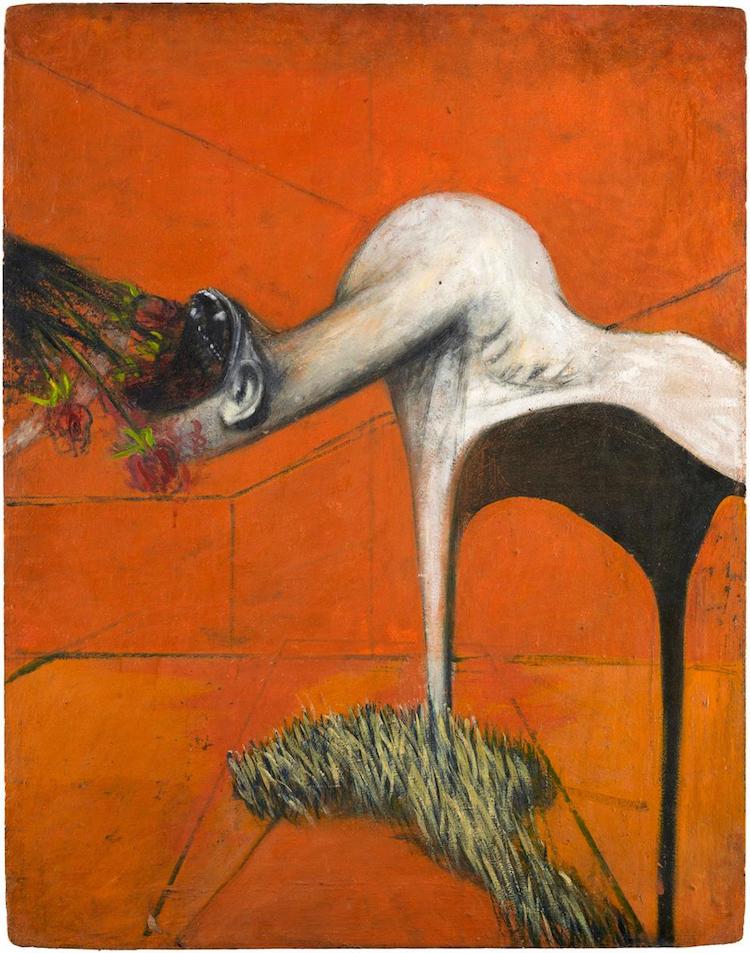

The paintings are, from top down: ‘Fury’ by Francis Bacon; Pierre Soulages, Untitled; Pablo Picassso, ‘The Charnel House’; Zdzislaw Beksiński, Untitled; Salvador Dalí, ‘The Face of War’; Francisco Goya’s ‘Saturn Devouring His Son’; Hieronymus Bosch, ‘The Last Judgment’ (detail).

So-called ‘lone wolf’ attacks are not the same as jihadi networks, which are obviously easier to maintain the larger the local Muslim community. Also, the description of radicalisation you give is not that used, for example, by the NYPD study.

Click to access NYPD_Report-Radicalization_in_the_West.pdf

‘Lone wolves’ rarely act totally alone, but their ‘networks’ are often friendship groups, rather than ‘jihadi networks’ as we commonly think of them. The NYPD study to which you link is in fact a classic of the kind of radicalisation thesis I am taking about. See my discussion of it in the New York Times.