This essay was published in the Observer, 3 September 2017, under the headline ‘Fostering row exposes how words fail us when we talk about Muslims in Britain’.

Court cases involving children being taken into care are inevitably messy. There are deep emotions involved and conflicting viewpoints. Parents are often angry, children confused and fearful. Those outside the process can find it difficult to discern the facts, as much of the decision-making takes place behind closed doors.

Given all this, it was perhaps inevitable that the explosive report in the Times last week – about the distress of a five-year-old girl in east London placed in foster care with a Muslim family – should unravel. What was not inevitable was the way in which it unravelled or the way that the story was framed to begin with. From the opening headline – ‘Christian child forced into Muslim foster care’ – this was a polemic in the guise of an investigation.

In no context other than a polemic about Muslims would the five-year-old have been described as a ‘Christian girl’. Whether that is even true is still unclear. While the mother describes her daughter as ‘of Christian heritage’, court documents ‘including the assessment of the maternal grandparents state that they are of a Muslim background but are non-practising’.

Many of the allegations – that the original foster parents did not speak English, that they told the girl that ‘Christmas and Easter are stupid’ and would not allow her to wear a cross – remain unverified. Tower Hamlets council denies the claims and the court adjudication makes no mention of them. According to the court, the mother has unspecified ‘concerns in respect of the foster carers’ but ‘has at no stage applied to the court for a change of foster carer’, suggesting that the concerns may not be that profound.

This may have been an individual foster case poorly handled by the local authority, though even that is not established. What it wasn’t was an expression of a clash of civilisations, of a ‘Christian’ child ‘forced into Muslim foster care’.

Many critics have dismissed the reporting as straightforward media bigotry. Clearly, there is an element of bigotry involved in some of the media responses. But the debate around the case also throws light on a host of other issues, in particular, the fraught ways in which we think of ‘culture’ and the inability of all sides to find an adequate language through which to speak about questions concerning Muslims and islam.

One issue on which all sides seem agreed is the need for ‘cultural matching’: the belief that a fostered child is best served living with carers who are of the same racial, cultural and religious background.

This might seem like common sense. But what it actually means is far from straightforward. Would a Christian child be better off in a liberal, open Muslim home or in a strictly observant, conservative Christian home? The answer is not necessarily clear. We don’t know the veracity of the allegations that one of the Tower Hamlets foster families disparaged Christmas and Easter and banned the cross. Suppose the claims are true. Would a Muslim child have thrived in such a household any more than a Christian child?

Like much public policy aimed at minority communities, ‘cultural matching’ treats people not according to their particular needs but by virtue of the cultural or faith boxes into which they have been placed. Cultural labels, though, rarely help define individual wants and aspirations. In any fostering environment, cultural matching matters less than the ability of the carers to nurture whatever identity the child is developing. It is worth remembering that a child needs fostering in the first place because remaining in its original ‘culturally matched’ home has been deemed detrimental to its interests.

This is not simply an argument for good parenting and care. What the Tower Hamlets case reveals is also how problematic are our conceptions of culture and of cultural differences.

This summer, a furore erupted when a couple of Indian Sikh background, Sandeep and Reena Mander, were apparently denied the chance to adopt a child. Their local council, Windsor and Maidenhead, deemed that the Manders’ ethnic and cultural background made them unsuitable to adopt white children and the only children in council care were white. Most newspapers, including the Times, were sympathetic to the Manders’ plight.

Many saw the attitude of Windsor and Maidenhead council, as many now see the approach of the Times, as a case of straightforward racism. But, as I wrote in the Observer then, ‘the problem runs much deeper’ and ‘speaks to a broader confusion about the relationship between race and culture’.

In the past, adoption and fostering policies were deeply shaped by racist attitudes. Racist policymakers balked at the idea of non-white or non-Christian parents bringing up white Christian children. Those old ideas of racial inferiority and superiority are less openly espoused these days. But the way we talk about ‘culture’ now often echoes the way once people talked of race. Many today view cultures as fixed, bounded entities, each the property only of certain people, and recoil at the thought of a child being brought up outside his or her given heritage. So, some are outraged by a Christian child being brought up by Muslim foster parents, just as some are by the idea of a white family bringing up a black child.

For many, it is not cultural balkanisation but racism that shapes contemporary attitudes to Islam. The portrayal of Muslims in the reporting of the Tower Hamlets foster case, they argue, makes sense only against a background of deeply entrenched hostility. Here, too, the issues are more complex. There is certainly hostility to Muslims, but this is often is mirrored by a fear of offending Muslims or of appearing racist.

The Times’ chief investigative reporter, Andrew Norfolk, who broke the fostering story last week, also first exposed, five years ago, the scandal of the Rotherham child abuse case. His reporting caused a national outcry and led eventually to an official inquiry that revealed that between 1997 and 2013, 1,400 young people, mainly white girls, had been abused and raped, largely by men of Pakistani or Kashmiri background, while the authorities turned a blind eye. Several other similar abuse cases have emerged since, including the conviction of 18 people in Newcastle last month.

Norfolk’s reporting on the Rotherham abuse was, unlike his coverage of the Tower Hamlets fostering case, meticulous and thorough. He was garlanded with awards, including the Paul Foot and Orwell prizes for journalism in 2013 and news reporter of the year and the Hugh Cudipp prize at the British Press Awards for 2014.

What distinguishes the Rotherham scandal and the Tower Hamlets case is not simply the care of the reporting but also the response to the abuse. Writing in the Sun, the former equalities chief Trevor Phillips claimed last week that the actions of Tower Hamlets council were ‘akin to child abuse’. It was nothing of the sort. The ‘abuse’ was largely invented by the media.

In Rotherham, on the other hand, the abuse was distressingly real. One of the reasons it was allowed to run unchecked for so long was the fear of many in authority, from social workers to police officers, of being labelled ‘racist’ were they to take seriously allegations against men of Muslim origin. After the story broke, there was continued nervousness among liberals of discussing the ethnicity and faith of the abusers, for fear of entrenching anti-Muslim abuse. The controversy over the Rotherham MP Sarah Champion, who resigned last month as shadow equalities minister, after writing an article in the Sun claiming that ‘Britain has a problem with British Pakistani men raping and exploiting white girls’, reveals the continued difficulties liberals have in knowing how to discuss the issue.

There is a difference between saying that certain Muslims committed heinous acts and saying that they did so because they were Muslims (though that may sometimes be the case) or that many or most Muslims act in a similar fashion. But liberal nervousness only paves the way for bigots to ride roughshod over such distinctions and to target all Muslims as the Other.

It also feeds into a broader fear of criticising Islam. Progressive critics of Islam are often attacked as ‘Islamophobes’ for challenging homophobia or misogyny within Muslim communities. The blurring of the distinction between bigotry against Muslims and criticisms of Islam is dangerous. On the one hand, it enables many to condemn legitimate criticisms of Islam or of attitudes within Muslim communities as ‘Islamophobic’. On the other, it permits those who promote hatred to dismiss condemnation of that hatred as stemming from an illegitimate desire to avoid criticism of Islam. Conflating criticism and bigotry makes it more difficult to engage in a rational discussion about where and how to draw the line between the two.

The Rotherham and Tower Hamlets cases, and the debates around them, reveal the polarised ways in which Muslims are discussed in Britain. It is a discussion too often trapped between hostility towards Muslims and a fear of creating such hostility or of offending Muslims.

Neither side is able to talk about Muslims as a normal part of British life, with the usual range of achievements and inadequacies, but only as ciphers for other issues. More than simply bigotry, this failure to find an adequate language through which to discuss Muslims and Islam bedevils public debate.

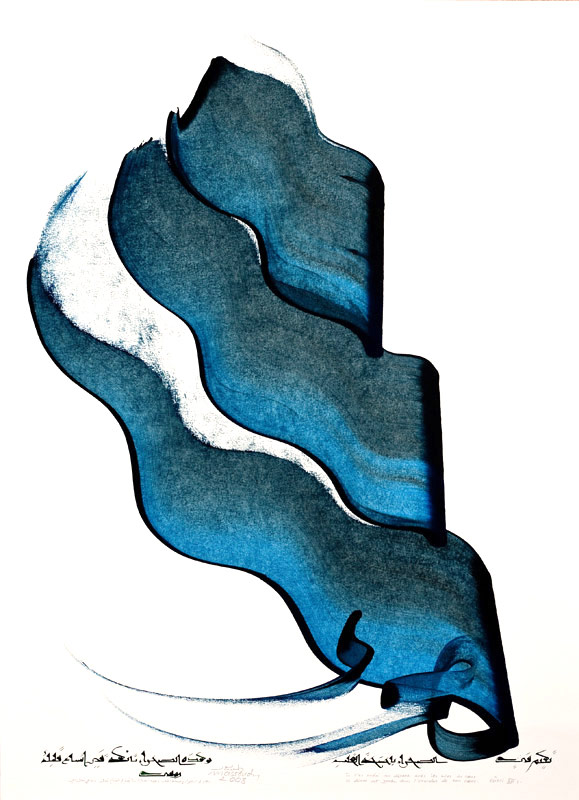

The images are all modern modern calligraphic art. From top down: Babak Rashvand, ‘Love’; Hassan Massoudy, ‘Untitled’; and Helen Abbas, ‘Ramad (Ashes) 03’.

“Neither side is able to talk about Muslims as a normal part of British life, with the usual range of achievements and inadequacies, but only as ciphers for other issues.”

I don’t want to sound too heavy-handed, but aren’t you – as people so often are these days – somehow trying to avoid real issues by insisting on treating them at the meta-level of how they are talked about? The implication is on the one hand that if we could only find an effective way of “discussing” some problems at this meta level, we could somehow just on that basis solve them in substance, except that it is not really demonstrated how we could really pull ourselves up by our own discursive bootstraps…so the overall effect, willed or not, seems to be to lead us even further from real engagement.

Your sentence I quoted at the top. It doesn’t really follow from the rest of the piece. You haven’t proved that talk about Muslims is usually not talk about Muslims but something else. You have only shown, perfectly sensibly, that people have perhaps intemperately strong (negative) views about Muslims (BTW, in extreme cases that sounds much more like obsession with the issue than using the issue as proxy!), or alternatively are fearful of saying anything that might sound to any degree unflattering about Muslims (all or some) because they fear either that this will cast them in a bad light themselves, or that it will make Muslims angry, or that it will not be conducive to tolerance of Muslims. None of this involves ciphers, even if it may involve some spoken or unspoken assumptions about what it is acceptable to say and why.

Getting ciphers out of the way, then, I fear that insofar as “neither side is able to talk about Muslims as a normal part of British life, with the usual range of achievements and inadequacies”, it’s because for various reasons that cannot all be reduced to some projection of the inner problems and demons of non-Muslims, Muslims do not collectively and in all lights appear to other British people as a normal part of British life. And as for “the usual range of achievements and inadequacies” – what on earth is the “usual range”? I don’t think that there is a binary choice between regarding Muslims as in all respects the same, or somehow in “range”(!) equivalent to other groups, and talking about Muslims as a cipher for something else, whatever that may be. It seems that this binary choice is yet another way of cutting off discussion of the real problems that Muslims rather distinctively pose (not all of them of course, but still distinctively) and that they face.

As usual Kenan an article that cuts through all the smoke and mirrors of mainstream commentary.

I think there is also something else going on with regard to Andrew Norfolk / The Times and now Sarah Champion and indeed others.

It is important to understand the recent context in which this is happening, after Rochdale/ Rotherham/Newcastle there is a general sense among the public of a cover up of some magnitude, questions are been asked and yet real avenues for discussion are been narrowed or closed.

Norfolk in particular has previously expressed a level of guilt of how he delayed for some considerable time the true level of abuse he had discovered and what to do about it,recently he and his employer seem to be over zealous almost in trying to overcome that guilt by acting as they have in the Tower Hamlets situation as indeed are other media outlets and the the CPS and Police themselves who are all complicit in the failures of the above situations.

That is not to say they should not be acting to bring to justice the perpetrators but we need to understand their too little too late approach, the horse had already bolted.

Similarly Champion is speaking out now, and rightly so, but again she has been a significant player in the whole Labour Party machinery in and around the local state institutions in Rotherham for some time,and despite resigning or been demoted she is hardly been very principled , she still remains a Labour MP, has made the relevant mark in the minds of Rotherham constituents for the future and i would suggest will await her return to the front bench.

But what they all fail to address, in fact cannot countenance, is the real source of many of these problems, multiculturalism itself, they are all complicit in ensuring it’s continuation and fermenting the divisions between us all while at the same time closing down debate that is absolutely vital if we are to find a way to discuss these issues freely and openly to find the solutions so desperately needed.

Not conflating religion and race would help

Kenan is right that words do matter because words are tools of thought, and it is difficult to think straight with bent tools. For example, the term “Islamophobia” fosters confusion as stated, and should be avoided. I note that Maajid Nawaz now uses the expression “Muslim-phobia” for anti-Muslim prejudice, and although one might regret the misuse of the “phoboa” concept the improvement is clear.